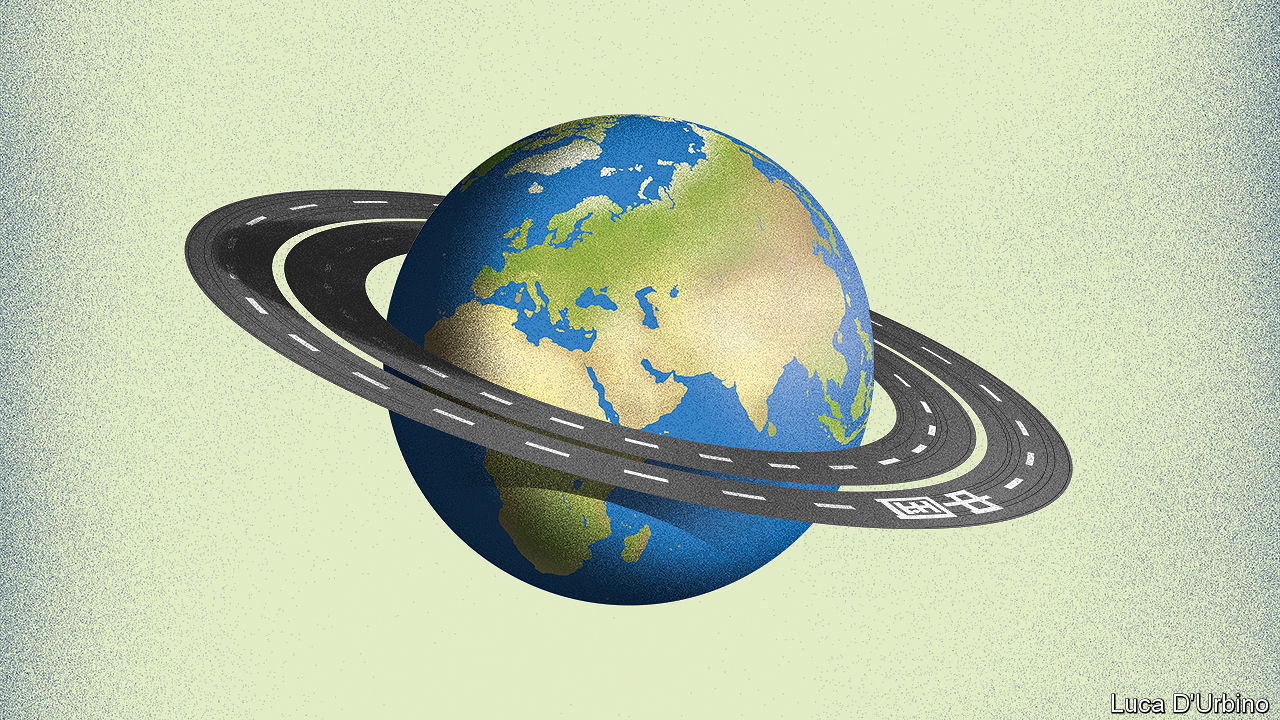

China’s belt-and-road plans are to be welcomed—and worried about

The “project of the century” may help some economies, but at a political cost

SHUNNING all false modesty, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, calls his idea the “project of the century”. The country’s fawning media hail it as a gift of “Chinese wisdom” to the world’s development. As for the real meaning of the clumsy metaphor to describe it—the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—debate rages.

The term itself is confusing. The “road” refers mostly to a sea route; the “belt” is on land. Countries eager for China’s financing welcome it as a source of investment in infrastructure between China and Europe via the Middle East and Africa. Those who fear China see it instead as a sinister project to create a new world order in which China is the pre-eminent power.

Chinese maps show the belt and road as lines that trace the routes of ancient “silk roads” that traversed Eurasia and the seas between China and Africa (see Briefing). That was the original conceit, but these days China talks about BRI as if it were a global project. The rhetoric has expanded to include a “Pacific Silk Road”, a “Silk Road on Ice” that crosses the Arctic Ocean and a “Digital Silk Road” through cyberspace.

To the extent that this is all about building infrastructure, the idea is welcome. Trillions of dollars’ worth of roads, railways, ports and power stations are needed in countries across Asia, Africa and Europe. China’s money and expertise could be a big help in spreading wealth and prosperity.

China says anyone can join in. Countries such as Azerbaijan and Georgia, which stand to benefit immensely from better connections to the world, are wildly enthusiastic. One of China’s motives is to strengthen security on its western flank by helping Central Asian countries prosper—thereby, it hopes, preventing them from becoming hotbeds of Islamist terrorism. Everyone would benefit from that, too.

But there are worries. The BRI is bound up with the growing cult around Mr Xi. State media call it “the path of Xi Jinping”. It has become shorthand for China’s overseas aid, state-led investment abroad and for Mr Xi’s much-ballyhooed “great-power diplomacy with Chinese characteristics”. China urges other countries to praise the BRI, so that their words can be relayed back home as propaganda. Few Chinese dare offer open criticism; that makes mistakes more likely.

The citizens of countries hosting BRI projects may come to regret their governments’ enthusiasm. Like all Chinese cash, the BRI billions come without pesky questions about human rights or corruption. Indeed, the terms are often shrouded in secrecy, raising fears that local politicians may benefit more than their people. Projects tend to require the use of lots of Chinese labour. BRI countries risk piling up dangerous amounts of debt, which some fear is designed to give China a strategic hold over them. Pakistan, one of the most important BRI countries, has just held an election in which candidates vied to take credit for Chinese investment; yet the debts are so large that, before long, Pakistan is likely to need an IMF bail-out.

Then there are possible security risks. In his metaphorical flights, Mr Xi sometimes speaks of his belt and road as a single thoroughfare, a “road of peace”. But what if the Chinese navy were to take advantage of ports such as Hambantota? This was repossessed by a Chinese state-owned firm after the Sri Lankan government struggled to repay the debts it had amassed to build it. Military planners worry that China could develop a string of such berths that its ships could use to extend their reach far beyond China’s shores.

Analysts in Asia and the West believe that China wants to displace America as the Asian hegemon. The BRI could end up furthering that plan, even if it is not its focus. China’s crude maps show the belt and road running through disputed territory, including the bitterly contested waters of the South China Sea where China has been busy building fortresses on reefs.

Some Asian countries, including India and Vietnam, are wary and most Western countries share their unease. Last year America’s defence secretary, James Mattis, said that: “No one nation should put itself into a position of dictating [BRI]”. In January France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, warned that the BRI “cannot be the roads of a new hegemony that will make the countries they traverse into vassal states.” He added: “The ancient silk roads were never purely Chinese…These roads are to be shared and they cannot be one-way.”

The world can also use its influence to make the BRI more beneficial. Even China’s billions cannot finance everything on offer. Money coming from the West, from the European Union and from institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF should be lent according to international standards—including on such things as transparency, environmental safeguards, public procurement and debt sustainability. So long as they are good projects, let China include them in the BRI if it wants to.

Last is security. The way to assuage fears about the BRI’s threat to the balance of power is not by trying to frustrate China’s efforts, let alone by starting a trade war or by pulling America’s armed forces out of Asia, as President Donald Trump sometimes seems to contemplate. On the contrary, the balance of risks and benefits of the BRI is related to America’s commitment to Asia. If the United States is engaged, the world can mitigate the dangers of BRI and reap its rewards. If not, the risks will outweigh the benefits. The BRI is yet one more argument for America to stay in Asia.

The term itself is confusing. The “road” refers mostly to a sea route; the “belt” is on land. Countries eager for China’s financing welcome it as a source of investment in infrastructure between China and Europe via the Middle East and Africa. Those who fear China see it instead as a sinister project to create a new world order in which China is the pre-eminent power.

Latest stories

All roads lead to Beijing

One cause of confusion is that the BRI is not a single plan at all. A visitor to its website would click in vain to find a detailed explanation of its aims. There is no blueprint of the kind that China’s leaders love: so many billions of dollars to be spent, so many kilometres of track to be laid or so much new port capacity to be built by such-and-such a date.Chinese maps show the belt and road as lines that trace the routes of ancient “silk roads” that traversed Eurasia and the seas between China and Africa (see Briefing). That was the original conceit, but these days China talks about BRI as if it were a global project. The rhetoric has expanded to include a “Pacific Silk Road”, a “Silk Road on Ice” that crosses the Arctic Ocean and a “Digital Silk Road” through cyberspace.

To the extent that this is all about building infrastructure, the idea is welcome. Trillions of dollars’ worth of roads, railways, ports and power stations are needed in countries across Asia, Africa and Europe. China’s money and expertise could be a big help in spreading wealth and prosperity.

China says anyone can join in. Countries such as Azerbaijan and Georgia, which stand to benefit immensely from better connections to the world, are wildly enthusiastic. One of China’s motives is to strengthen security on its western flank by helping Central Asian countries prosper—thereby, it hopes, preventing them from becoming hotbeds of Islamist terrorism. Everyone would benefit from that, too.

But there are worries. The BRI is bound up with the growing cult around Mr Xi. State media call it “the path of Xi Jinping”. It has become shorthand for China’s overseas aid, state-led investment abroad and for Mr Xi’s much-ballyhooed “great-power diplomacy with Chinese characteristics”. China urges other countries to praise the BRI, so that their words can be relayed back home as propaganda. Few Chinese dare offer open criticism; that makes mistakes more likely.

The citizens of countries hosting BRI projects may come to regret their governments’ enthusiasm. Like all Chinese cash, the BRI billions come without pesky questions about human rights or corruption. Indeed, the terms are often shrouded in secrecy, raising fears that local politicians may benefit more than their people. Projects tend to require the use of lots of Chinese labour. BRI countries risk piling up dangerous amounts of debt, which some fear is designed to give China a strategic hold over them. Pakistan, one of the most important BRI countries, has just held an election in which candidates vied to take credit for Chinese investment; yet the debts are so large that, before long, Pakistan is likely to need an IMF bail-out.

Then there are possible security risks. In his metaphorical flights, Mr Xi sometimes speaks of his belt and road as a single thoroughfare, a “road of peace”. But what if the Chinese navy were to take advantage of ports such as Hambantota? This was repossessed by a Chinese state-owned firm after the Sri Lankan government struggled to repay the debts it had amassed to build it. Military planners worry that China could develop a string of such berths that its ships could use to extend their reach far beyond China’s shores.

Analysts in Asia and the West believe that China wants to displace America as the Asian hegemon. The BRI could end up furthering that plan, even if it is not its focus. China’s crude maps show the belt and road running through disputed territory, including the bitterly contested waters of the South China Sea where China has been busy building fortresses on reefs.

Some Asian countries, including India and Vietnam, are wary and most Western countries share their unease. Last year America’s defence secretary, James Mattis, said that: “No one nation should put itself into a position of dictating [BRI]”. In January France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, warned that the BRI “cannot be the roads of a new hegemony that will make the countries they traverse into vassal states.” He added: “The ancient silk roads were never purely Chinese…These roads are to be shared and they cannot be one-way.”

Keep those American signposts

What should the world do about the BRI? For a start, it needs to keep some perspective. Even if China does hope to use it as a political tool to beat back Western influence, Beijing is bound to face difficulties, as projects go awry, debts go bad and people grow hostile to China’s presence. History suggests that simply doling out money will not, on its own, usher in a Pax Sinica.The world can also use its influence to make the BRI more beneficial. Even China’s billions cannot finance everything on offer. Money coming from the West, from the European Union and from institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF should be lent according to international standards—including on such things as transparency, environmental safeguards, public procurement and debt sustainability. So long as they are good projects, let China include them in the BRI if it wants to.

Last is security. The way to assuage fears about the BRI’s threat to the balance of power is not by trying to frustrate China’s efforts, let alone by starting a trade war or by pulling America’s armed forces out of Asia, as President Donald Trump sometimes seems to contemplate. On the contrary, the balance of risks and benefits of the BRI is related to America’s commitment to Asia. If the United States is engaged, the world can mitigate the dangers of BRI and reap its rewards. If not, the risks will outweigh the benefits. The BRI is yet one more argument for America to stay in Asia.

No comments:

Post a Comment