A new Brexit plan creates fresh depths of chaos

And the worst is yet to come

A REALLY sensible government would have drawn up a plan for how to leave the European Union before calling a referendum on whether to do so. A sane one would have devised a strategy before triggering exit negotiations. Britain, by contrast, announced its departure plan on July 6th, when three-quarters of the time it has for talking to Brussels had already been used up. And even then the long-overdue reckoning with reality sent the government reeling.

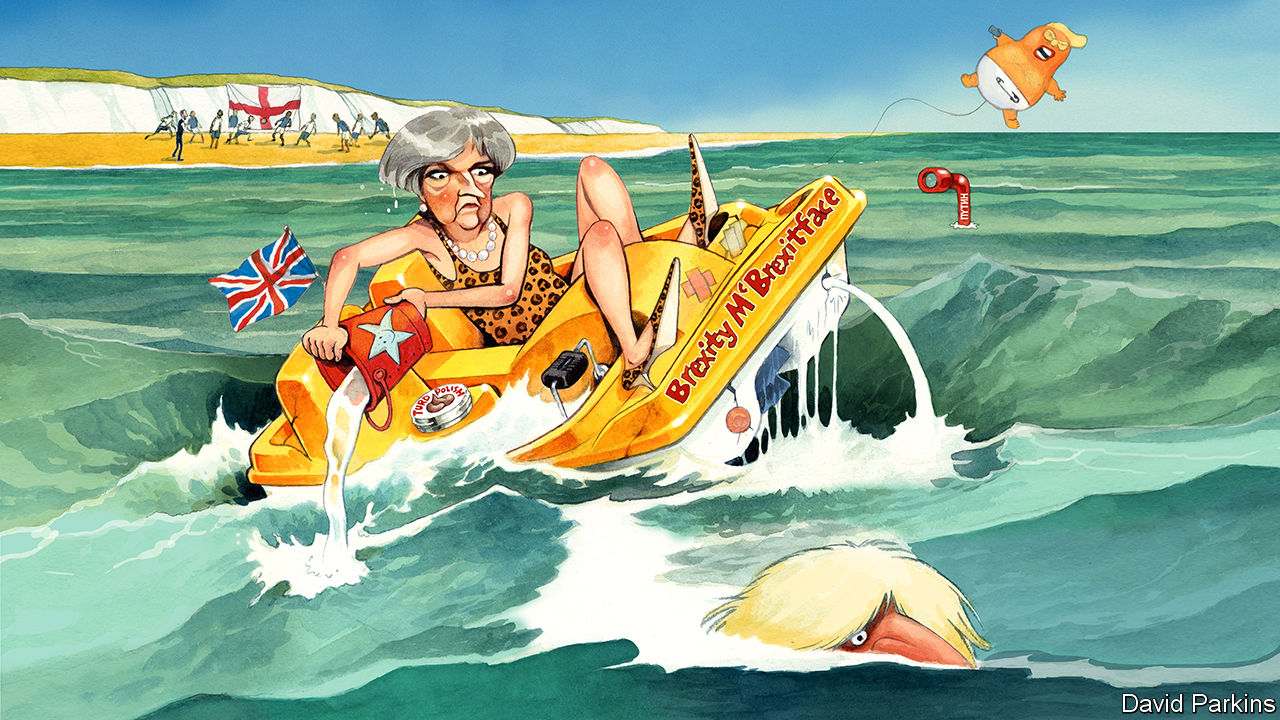

Two cabinet ministers and two Conservative Party vice-chairmen have quit; the foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, said in his resignation letter that the Brexit “dream is dying”. Those abandoning ship are furious that Theresa May has dropped a hard separation from the EU for a softer deal, preserving many legal and economic ties. For now, the prime minister seems unsinkable (wooden objects tend to be). But her belated move towards a realistic Brexit has just begun. As the truth sinks in, more turmoil is in store. The task for Mrs May and the EU is to ensure that the Brexit project does not descend into anarchy.

This is Mrs May’s most realistic plan so far, and yet European leaders will demand that she go further. They say she has still not made clear how Britain plans to avoid a hard border in Ireland, something they insist is settled before any deal can be signed. Britain is likely to be told that, if it wants the benefits of the single market for goods, it must seek membership of the whole thing—which in turn means observing other rules, including free movement of labour. The EU will probably want ongoing payments into its budget, too (see article).

This will lead to a Brexit that satisfies almost nobody. Hardline Brexiteers already feel betrayed. This week Mr Johnson complained that Britain would be subject to EU laws without having a say in how they were made, and that obeying these rules would make it harder to do trade deals with other countries. That is true, and adding in budget payments and free movement will surely prompt further cabinet resignations and backbench rebellions.

Remainers are hardly jubilant, either. Many, including this newspaper, see ending up in a situation similar to Norway, bound to the EU but with little say in how it works, as the best Brexit possible—and certainly less bad than the hard sort, which would cause enduring harm to the country’s prosperity. But a soft Brexit is so obviously worse than what Britain has today as a member of the EU that it would underline more clearly than ever the folly of leaving.

As a result Mrs May might struggle to get a deal through Parliament, even though most MPs probably favour a soft Brexit. Although pragmatic Brexiteers and Remainers may back her, hardliners may be tempted to hold out for either a harder deal or for stopping Brexit altogether. Her task will be further complicated by Labour under Jeremy Corbyn, which has yet to produce its own coherent plan. It is likely to put party before country by voting against whatever deal Mrs May brings home, in the hope of bringing down the government. That means even a small rebellion by Tory hardliners could be enough to defeat the plan.

Where does this leave Britain? Do not look to Brexiteers for answers. Although they complain that the people have been betrayed, they have still not explained how Britain could cut all ties with the EU while preserving trade links to what is by far Britain’s largest market. Mr Johnson did not even mention Ireland in his resignation letter this week. It is as if Brexiteers have spent so many years in opposition attacking the EU that they are flummoxed by the idea of coming up with a workable plan. While Mrs May at last faces up to the painful trade-offs that Brexit always required, those who condemned her this week prefer to indulge their fantasies.

The EU could help—and has reason to. It is reluctant to give Britain a bespoke deal, for fear that its other restless members will angle for special treatment, too. This is why Eurocrats solemnly vow that nothing must undermine the single market.

But if the Brexit negotiations fail, and Britain crashes out without any deal at all, it would cause grave damage across Europe and beyond. And in some areas the EU has an incentive to offer concessions. The most glaring is security, where its hardline position is self-defeating. Britain is one of Europe’s two big military and intelligence powers. Limiting its role in projects such as the Galileo geolocation system, at a time when America is wavering on its NATO commitments and Russia is stirring up trouble, endangers all Europeans. Bending rules such as freedom of movement is harder. But the EU can help give Mrs May the cover she needs to sell the deal at home. If she wants to replace free movement with a “mobility framework” that does much the same thing, let her. If she wants market alignment on goods but not on services, so what?

That Britain has at last set a course for a soft Brexit is welcome. Getting there will be a very rough crossing indeed.

Two cabinet ministers and two Conservative Party vice-chairmen have quit; the foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, said in his resignation letter that the Brexit “dream is dying”. Those abandoning ship are furious that Theresa May has dropped a hard separation from the EU for a softer deal, preserving many legal and economic ties. For now, the prime minister seems unsinkable (wooden objects tend to be). But her belated move towards a realistic Brexit has just begun. As the truth sinks in, more turmoil is in store. The task for Mrs May and the EU is to ensure that the Brexit project does not descend into anarchy.

Latest stories

Men overboard

Mrs May’s Brexit plan marks a decisive shift. Her approach had previously consisted mainly of ruling things out: no single-market membership, no free movement of labour, no obedience to foreign judges. Now she has said what she wants. She proposes that Britain remain, in effect, in the single market for goods, and in a looser system of mutual recognition for services. In return she promises not to undercut EU standards for the environment, social policies or state aid. She proposes a dispute-resolution mechanism that implies a role for the European Court of Justice. And she suggests that Britain stay in a customs union with the EU until a clever new tariff-collection mechanism can be set up (which may well mean for ever).This is Mrs May’s most realistic plan so far, and yet European leaders will demand that she go further. They say she has still not made clear how Britain plans to avoid a hard border in Ireland, something they insist is settled before any deal can be signed. Britain is likely to be told that, if it wants the benefits of the single market for goods, it must seek membership of the whole thing—which in turn means observing other rules, including free movement of labour. The EU will probably want ongoing payments into its budget, too (see article).

This will lead to a Brexit that satisfies almost nobody. Hardline Brexiteers already feel betrayed. This week Mr Johnson complained that Britain would be subject to EU laws without having a say in how they were made, and that obeying these rules would make it harder to do trade deals with other countries. That is true, and adding in budget payments and free movement will surely prompt further cabinet resignations and backbench rebellions.

Remainers are hardly jubilant, either. Many, including this newspaper, see ending up in a situation similar to Norway, bound to the EU but with little say in how it works, as the best Brexit possible—and certainly less bad than the hard sort, which would cause enduring harm to the country’s prosperity. But a soft Brexit is so obviously worse than what Britain has today as a member of the EU that it would underline more clearly than ever the folly of leaving.

As a result Mrs May might struggle to get a deal through Parliament, even though most MPs probably favour a soft Brexit. Although pragmatic Brexiteers and Remainers may back her, hardliners may be tempted to hold out for either a harder deal or for stopping Brexit altogether. Her task will be further complicated by Labour under Jeremy Corbyn, which has yet to produce its own coherent plan. It is likely to put party before country by voting against whatever deal Mrs May brings home, in the hope of bringing down the government. That means even a small rebellion by Tory hardliners could be enough to defeat the plan.

Where does this leave Britain? Do not look to Brexiteers for answers. Although they complain that the people have been betrayed, they have still not explained how Britain could cut all ties with the EU while preserving trade links to what is by far Britain’s largest market. Mr Johnson did not even mention Ireland in his resignation letter this week. It is as if Brexiteers have spent so many years in opposition attacking the EU that they are flummoxed by the idea of coming up with a workable plan. While Mrs May at last faces up to the painful trade-offs that Brexit always required, those who condemned her this week prefer to indulge their fantasies.

The EU could help—and has reason to. It is reluctant to give Britain a bespoke deal, for fear that its other restless members will angle for special treatment, too. This is why Eurocrats solemnly vow that nothing must undermine the single market.

But if the Brexit negotiations fail, and Britain crashes out without any deal at all, it would cause grave damage across Europe and beyond. And in some areas the EU has an incentive to offer concessions. The most glaring is security, where its hardline position is self-defeating. Britain is one of Europe’s two big military and intelligence powers. Limiting its role in projects such as the Galileo geolocation system, at a time when America is wavering on its NATO commitments and Russia is stirring up trouble, endangers all Europeans. Bending rules such as freedom of movement is harder. But the EU can help give Mrs May the cover she needs to sell the deal at home. If she wants to replace free movement with a “mobility framework” that does much the same thing, let her. If she wants market alignment on goods but not on services, so what?

Throw her a lifebelt

And if Mrs May cannot win a Brexit vote? Then the EU should be prepared to grant Britain more time, to avoid it crashing out without a deal. To break the parliamentary impasse, Mrs May might have to go back to the people, either with yet another election or even a second referendum, setting out a concrete plan for Brexit rather than the vague, incompatible promises put before voters the last time round.That Britain has at last set a course for a soft Brexit is welcome. Getting there will be a very rough crossing indeed.

No comments:

Post a Comment