HANDY is creating a big business out of small jobs. The company finds

its customers self-employed home-helps available in the right place and

at the right time. All the householder needs is a credit card and a

phone equipped with Handy’s app, and everything from spring cleaning to

flat-pack-furniture assembly gets taken care of by “service pros” who

earn an average of $18 an hour. The company, which provides its service

in 29 of the biggest cities in the United States, as well as Toronto,

Vancouver and six British cities, now has 5,000 workers on its books; it

says most choose to work between five hours and 35 hours a week, and

that the 20% doing most earn $2,500 a month. The company has 200

full-time employees. Founded in 2011, it has raised $40m in venture

capital.

Handy is one of a large number of startups built around systems which

match jobs with independent contractors on the fly, and thus supply

labour and services on demand. In San Francisco—which is, with New York,

Handy’s hometown, ground zero for this on-demand economy—young

professionals who work for Google and Facebook can use the apps on their

phones to get their apartments cleaned by Handy or Homejoy; their

groceries bought and delivered by Instacart; their clothes washed by

Washio and their flowers delivered by BloomThat. Fancy Hands will

provide them with personal assistants who can book trips or negotiate

with the cable company. TaskRabbit will send somebody out to pick up a

last-minute gift and Shyp will gift-wrap and deliver it. SpoonRocket

will deliver a restaurant-quality meal to the door within ten minutes.

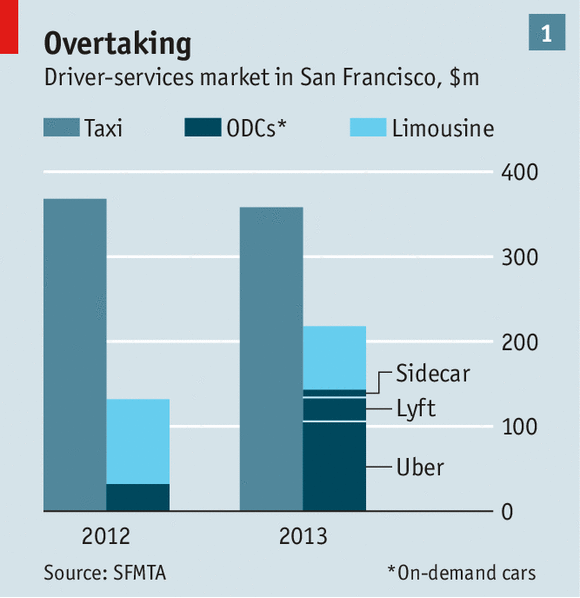

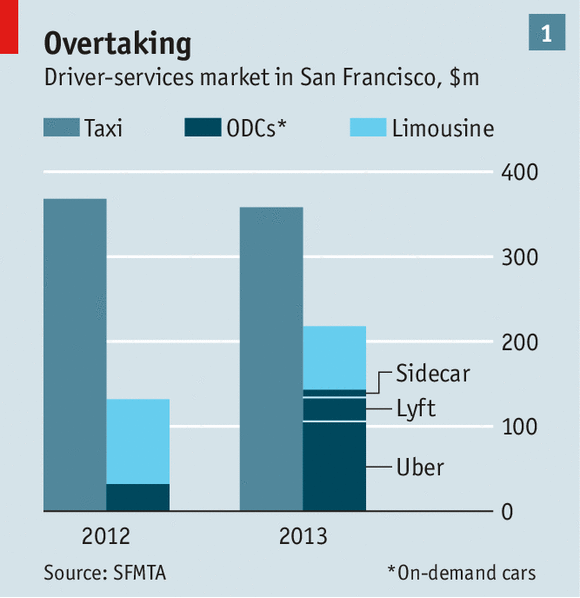

The obvious inspiration for all this is Uber, a car service which was

founded in San Francisco in 2009 and which already operates in 53

countries; insiders say it will have sales of more than $1 billion in

2014. SherpaVentures, a venture-capital company, calculates that Uber

and two other car services, Lyft and Sidecar, made $140m in revenues in

San Francisco in 2013, half what the established taxi companies took

(see chart 1), and the company shows every sign of doing the same

wherever local regulators give it room. Its latest funding round valued

it at $40 billion. Even in a frothy market, that is a remarkable figure.

Bashing Uber has become an industry in its own right; in some

circles, though, applying its business model to any other service

imaginable is even more popular. There seems to be a near-endless

succession of bright young people promising venture capitalists that

they can be “the Uber of X”, where X is anything one of those bright

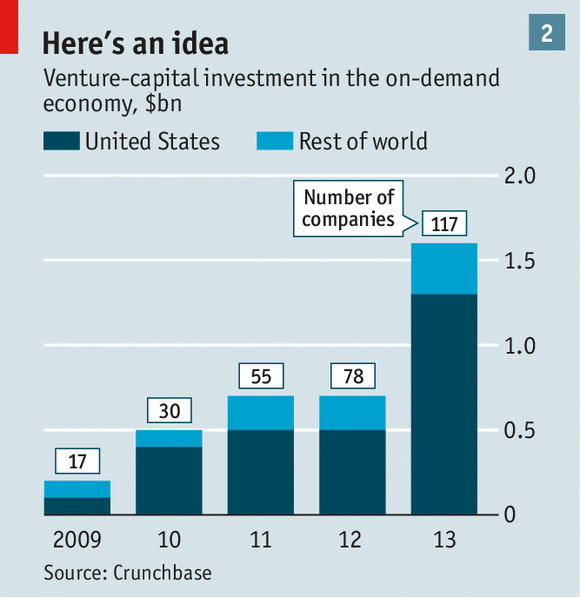

young people can imagine wanting done for them (see chart 2). They have

created a plethora of on-demand companies that put time-starved urban

professionals in timely contact with job-starved workers, creating a

sometimes distasteful caricature of technology-driven social disparity

in the process; an article about the on-demand economy by Kevin Roose in

New York magazine began with the revelation that the housecleaner he hired through Homejoy lived in a homeless shelter.

This boom marks a striking new stage in a deeper transformation.

Using the now ubiquitous platform of the smartphone to deliver labour

and services in a variety of new ways will challenge many of the

fundamental assumptions of 20th-century capitalism, from the nature of

the firm to the structure of careers.

The young Turks

The new opportunities that technology offers for matching jobs to

workers were being exploited well before Uber. Topcoder was founded in

2001 to give programmers a venue to show off. In 2013, it was bought by

Appirio, a cloud-services company, and now specialises in providing the

services of freelance coders. Elance-oDesk offers 4m companies the

services of 10m freelances. The model is also gaining ground in the

professions. Eden McCallum, which was founded in London in 2000, can tap

into a network of 500 freelance consultants in order to offer

consulting services at a fraction of the cost of big consultancies like

McKinsey. This allows it to provide consulting to small companies as

well as to concerns like GSK, a pharma giant. Axiom employs 650 lawyers,

services half the

Fortune 100 companies, and

enjoyed revenues of more than $100m in 2012. Medicast is applying a

similar model to doctors in Miami, Los Angeles and San Diego. Patients

order a doctor by touching an app (which also registers where they are).

A doctor briefed on the symptoms is guaranteed to arrive within two

hours; the basic cost is $200 a visit. Not least because it provides

malpractice insurance, the company is particularly attractive to

moonlighters who want to top up their income, younger doctors without

the capital to start their own practices and older doctors who want to

set their own timetables.

The Los Angeles-based Business Talent Group provides bosses on tap

for companies that want to tackle a specific problem without adding

another senior executive to the payroll: Fox Mobile Entertainment, an

online-content provider, turned to it for a temporary creative director

to produce a new line of products. Creative companies add a twist to the

model: they demand ideas, rather than labour and services, and give a

prize or prizes only to the ones they find interesting. Innocentive has

applied the prize idea to corporate R&D; it turns companies’

research needs into specific problems and pays for satisfactory

solutions to them.

A job for the afternoon

Tongal does the same thing with its network of 40,000 video-makers.

In 2012 Colgate-Palmolive, a consumer-goods company, offered $17,000 to

anyone who could make a 30-second advertisement for the internet. The ad

was so good that the company showed it at the Super Bowl alongside

blockbuster ads that cost hundreds of times more. Members of the Quirky

network post their product ideas on the company’s website. Other members

vote on the attractiveness of each idea and come up with ways of

turning it into reality. Since its birth in 2009 the company has

acquired over a million members and brought 400 products to the shops.

Perhaps the most striking of all the on-demand services is Amazon’s

Mechanical Turk, which allows customers to post any “human intelligence

task”, from flagging objectionable content on websites to composing text

messages; workers on the site choose what to do according to task and

price. The set-up uses to the full most of the capabilities and

advantages that make on-demand business models attractive: no need for

offices; no full-time contract employees; the clever use of computers to

repackage one set of people’s needs into another set of people’s tasks;

and an ability to access spare time and spare cognitive capacity all

across the world.

The idea that having a good job means being an employee of a

particular company is a legacy of a period that stretched from about

1880 to 1980. The huge companies created by the Industrial Revolution

brought armies of workers together, often under a single roof. In its

early stages this was a step down for many independent artisans who

could no longer compete with machine-made goods; it was a step up for

day-labourers who had survived by selling their labour to gang masters.

These companies introduced a new stability into work, a structure

which differentiated jobs from one another more clearly than before,

thus providing defined roles and new paths of career progress. Many of

the jobs were unionised, and the unions fought to improve their members’

benefits. Governments eventually built stable employment along these

lines into the heart of welfare legislation. A huge class of

white-collar workers enjoyed secure jobs administering the new economy.

For a while after the second world war everybody seemed to benefit

from this model: workers got security, benefits and steady wage rises;

companies got a stable workforce in which they could invest with a fair

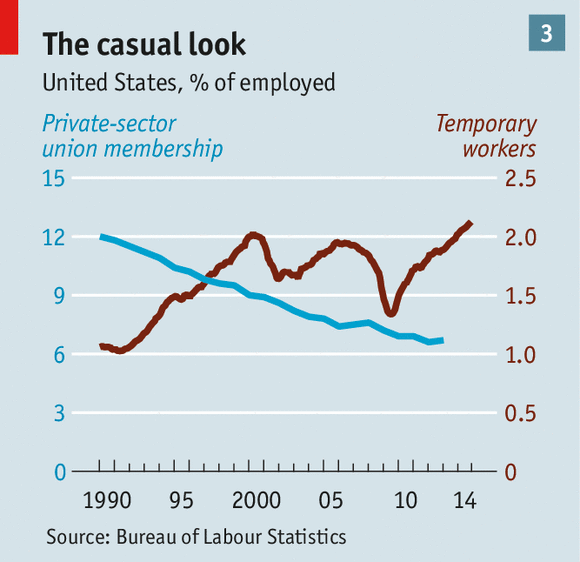

expectation of returns. But the model started to get into trouble in the

1970s, thanks first to deteriorating industrial relations and then to

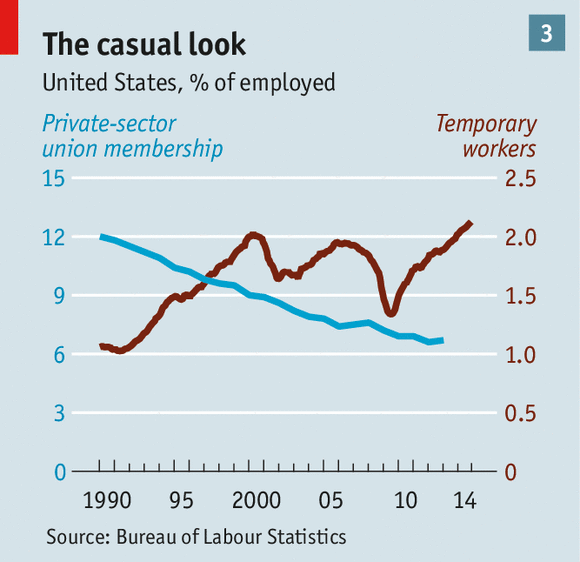

globalisation and computerisation. Trade unions have lost power in the

private sector, particularly in America and Britain, where legislation

has reduced their ability to take action (see chart 3). Companies kept

stricter control of their labour costs, increasingly contracting out

production in industrial businesses and re-engineering

middle-management. Computerisation and improved communications then sped

the process up, making it easier for companies to export jobs abroad,

to reshape them so that they could be done by less skilled contract

workers, or to eliminate them entirely.

This has all resulted in a more rootless and flexible labour force.

Pensioners and parents wanting or needing to spend more time on child

care swell the ranks of students and the straightforwardly unemployed. A

recent study by the Freelancers Union, a pressure group for freelance

workers, suggests that one in three members of the American workforce

(and a higher proportion of younger people) do some freelance work.

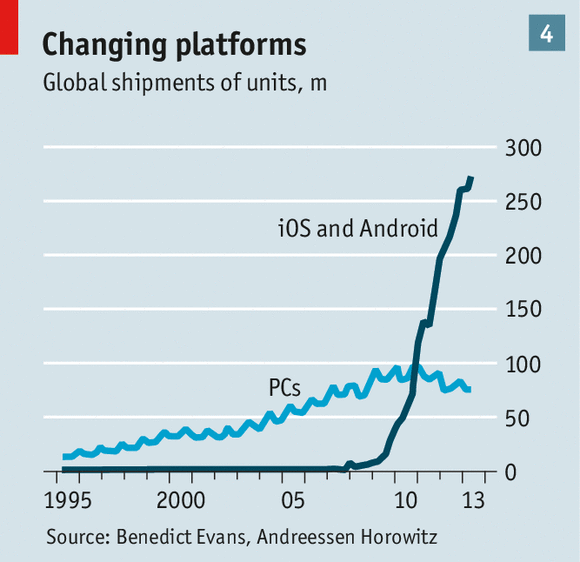

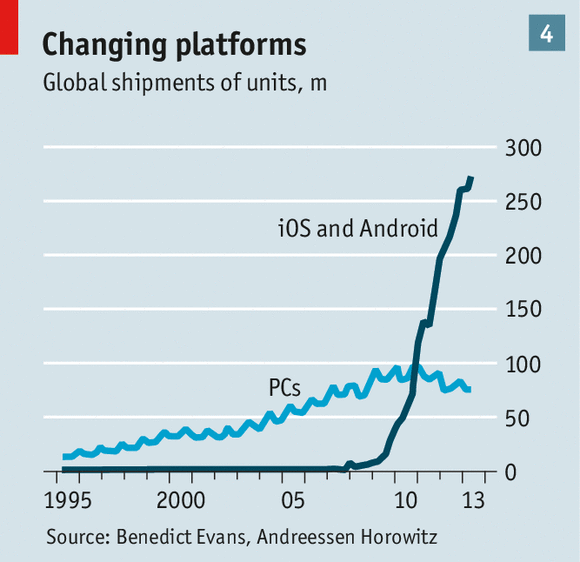

The on-demand economy is the result of pairing that workforce with

the smartphone, which now provides far more computing power than the

desktop computers which reshaped companies in the 1990s, and to far more

people (see chart 4 on next page). According to Benedict Evans of

Andreessen Horowitz, the new iPhones sold over the weekend of their

release in September 2014 contained 25 times more computing power than

the whole world had at its disposal in 1995. Connected to each other and

to yet more data and processing power in the cloud, these devices are

letting people design or find ad hoc answers to all sorts of business

problems previously solved by the structure of the firm.

Coase and effect

The way economists understand firms is largely based on an insight of

the late Ronald Coase. Firms make sense when the cost of organising

things internally through hierarchies is less than the cost of buying

things from the market; they are a way of dealing with the high

transaction costs faced when you need to do something moderately

complicated. Now that most people carry computers in their pockets which

can keep them connected with each other, know where they are,

understand their social network and so on, the transaction costs

involved in finding people to do things can be pushed a long way down.

This has a range of knock-on consequences, all of which are becoming

key features of the on-demand economy. One is further division of

labour. Thomas Malone, of the MIT Sloan School of Management, argues

that computer technology is producing an age of hyper-specialisation, as

the process that Adam Smith observed in a pin factory in the 1760s is

applied to more sophisticated jobs.

Another is the ability to tap underused capacity. This applies not

just to people’s time, but also to their assets: to drive for Lyft or

Uber, you do need a car. The on-demand economy is in many ways a

continuation of what has been called the “sharing economy” exemplified

by Airbnb, a company which turns apartments into guesthouses and their

owners into hoteliers. For people with few assets, though, on-demand

labour markets matter more.

And new areas are being opened to economies of scale. SpoonRocket

prepares its food in two central kitchens in San Francisco and Berkeley.

It delivers food quickly because it keeps a fleet of cars, equipped

with thermal bags to keep the food warm, roaming the streets of San

Francisco. “We’re like a gigantic cafeteria serving all of San

Francisco,” says Anson Tsui, one of the company’s founders.

Scheduling success

The aim of the on-demand companies is to exploit low transaction

costs in a number of ways. One key is providing the sort of trust that

encourages people to take a punt on the unfamiliar. Customers worry

about the quality of their temporary employees: nobody wants to give the

key to their apartment to a potential burglar, or their health details

to a dud doctor. Potential freelances, for their part, do not want to

have to deal with deadbeats: about 40% of freelances are currently paid

late.

On-demand companies like Handy provide customers with a guarantee

that workers are competent and honest; Oisin Hanrahan, the company’s

founder, says that more than 400,000 people have applied to join the

platform, but only 3% of applicants get through its selection and

vetting process. The workers, for their part, can hope for a steady flow

of jobs and prompt payment with minimal fuss. Handy’s computer system

also tries to schedule each worker’s jobs in such a way as to minimise

travel time.

Despite these capabilities, Handy is not necessarily looking at huge

success, any more than the other Ubers-of-X are. There are three reasons

for scepticism about their chances.

The first is that on-demand companies trying to keep the costs to

their clients as low as possible have difficulties training, managing

and motivating workers. MyClean, a cleaning service based in New York

City, tried using purely contract workers, but discovered that it got

better customer ratings if it used permanent staff. The company thinks

that better services justify higher labour costs. Uber drivers complain

that the company pays them like contract workers while seeking to manage

them like regular employees: they are told to take regular rather than

premium fares, but are not reimbursed for their fuel. America’s

gathering economic recovery may make it harder for companies to attract

casual labour as easily as they have done in the past few years.

The second problem is that on-demand companies seem likely to be

plagued by regulatory and political problems if they get large enough

for people to notice them. American on-demand companies are terrified

that they will be stuck with retrospective labour bills if the courts

force them to reclassify their workers as regular employees rather than

contract workers (a classification which is not always consistent from

jurisdiction to jurisdiction, raising the level of anxiety). Handy at

one point included a clause in its contracts imposing any such

retrospective costs on its clients, though it has now withdrawn it.

Faced by the threat of Uber, established taxi companies around the

world have organised strikes, filed lawsuits and leant on regulators. In

the Netherlands Uber has been banned; South Korea is treating it as an

illegal taxi service. In Germany anti-Uber feeling has nurtured a

broader criticism of “Plattform-Kapitalismus”; its perceived readiness

to reduce all aspects of people’s lives, from spare rooms to spare time,

to assets to be auctioned off is seen as deeply dehumanising. But such

protests often act as advertising for the services they are aimed

against. And a recent study revealed that American politicos spend more

on Uber than on regular taxis when campaigning, a strong indication that

the road ahead is likely to remain clear.

The third issue is size. The on-demand model obviously has network

effects: the home-help company with the most help on the books has the

best chance of providing a handyman at 10:30 sharp. Yet scaling up may

be difficult when barriers to entry are low and bonds of loyalty are

non-existent. It will be hard to get workers to be loyal to just one

middleman. A number of Uber drivers also work for Lyft.

In many service industries it is hard to see obvious economies of

scale on a national or global level. Being the best dry-cleaning service

in Cleveland does not necessarily offer a killer edge in Cologne. And

taste can be fickle, especially with companies that often look like

positional goods that trade, at least in part, on the cachet that they

confer to their consumers. Many of the people who currently regard

SpoonRocket as cool may drop it if it becomes a national brand.

On-demand companies may find themselves stuck in a world of low margins,

high promotional costs and labour churn as they struggle to attain the

sort of market dominance that locks in their network advantages. Alfred,

a subscription service, is already aggregating the work of specific

on-demand companies such as Instacart and Handy to offer its Boston

members a one-stop shop; such aggregation could drive down prices for

the basic on-demand providers yet further.

Everyone a corporation

Even if the eventual on-demand victors do carve out profitable

domestic-service businesses, many observers doubt that their model is

more broadly applicable. Some critics argue that on-demand companies

like BloomThat and Handy may be capable of delivering flowers or

cleaning houses, but when it comes to companies in the main flow of the

knowledge economy they are destined to remain marginal. This objection,

though, is not very convincing. The sort of people currently using Uber

are subject to the same forces as the people who drive them from place

to place.

The knowledge economy is subject to the same forces as the industrial

and service economies: routinisation, division of labour and

contracting out. A striking proportion of professional knowledge can be

turned into routine action, and the division of labour can bring big

efficiencies to the knowledge economy. Topcoder can undercut its rivals

by 75% by chopping projects into bite-sized chunks and offering them to

its 300,000 freelance developers in 200 countries as a series of

competitive challenges. Knowledge-intensive companies are already

contracting out more work to the market, partly to save costs and partly

to free up their cleverest workers to focus on the things that add the

most value. In 2008 Pfizer, a pharma company, undertook a huge

self-examination under the heading PfizerWorks. It realised that its

most highly skilled workers were spending 20% to 40% of their time on

routine work—entering data, producing PowerPoint slides, doing research

on the web. The company now contracts out much of this work.

Thus more and more of the routine parts of knowledge work can be

parcelled out to individuals, just as they were previously parcelled out

to companies. This could be bad news for the business models of

professional-service companies which use juniors to do fairly routine

work—thus providing the firm with income and the juniors with

training—while the partners do the more sophisticated stuff. As

on-demand solutions and automation prove applicable to more and more

routine work, that model becomes hard to sustain. InCloudCounsel

undercuts big law firms by as much as 80% thanks to an army of

freelances that processes legal documents (such as licences,

accreditation and non-disclosure agreements) for a flat fee.

The key role that cutting things up into routines plays in both

spheres suggests that the interaction between the on-demand economy and

automation will be a complex one. Gobbetising jobs with the aim of

parcelling them out to people who don’t see or need to see the big

picture is not that different from gobbetising them in a way that allows

automation. Often the first activity may prove a prelude to the second;

it is easy to see Uber as a forerunner to an eventual system that has

no drivers at all. In other cases, though, the cost-efficiency of

contracting out may reduce the incentives to automate.

What sort of world will this on-demand model create? Pessimists worry

that everyone will be reduced to the status of 19th-century dockers

crowded on the quayside at dawn waiting to be hired by a contractor.

Boosters maintain that it will usher in a world where everybody can

control their own lives, doing the work they want when they want it.

Both camps need to remember that the on-demand economy is not

introducing the serpent of casual labour into the garden of full

employment: it is exploiting an already casualised workforce in ways

that will ameliorate some problems even as they aggravate others.

The on-demand economy is unlikely to be a happy experience for people

who value stability more than flexibility: middle-aged professionals

with children to educate and mortgages to pay. On the other hand it is

likely to benefit people who value flexibility more than security:

students who want to supplement their incomes; bohemians who can afford

to dip in and out of the labour market; young mothers who want to

combine bringing up children with part-time jobs; the semi-retired,

whether voluntarily so or not.

Megan Guse, a law graduate, says that the on-demand model allows her

to combine a career as a lawyer with her taste for travel. “A lot of my

friends that have gone the Big Law route have these stories about having

to cancel weddings, vacations and miss family events. I can continue

working while being in exotic places.” Flexibility is also valuable for

elite workers who want to wind down after decades of selling their soul

to their companies. Jody Greenstone Miller, the founder of Business

Talent Group, says that her company’s comparative advantage lies in

rethinking corporate time: by breaking up work into projects, she can

allow people to work for as long as they want.

A limited Utopia

The on-demand economy is good for outsiders and insurgents—and for

entrepreneurs trying to create new businesses using such people. Matt

Barrie, the founder of Freelance.com, links the fate of two groups of

potential winners: entrepreneurs in the rich world who have few

resources will be able to link up with workers in the poor world who

have little money. In Europe the labour market drives a wedge between

insiders who have lots of protections and outsiders who don’t; on-demand

arrangements may give outsiders a chance of breaking in. Thus in

countries such as France, Italy and Spain, on-demand companies may

improve the job chances of the young unemployed.

If this seems attractive, it is also a measure of the way that the

on-demand economy will contribute to pressure to reduce labour rights in

all sorts of situations; a growing abundance of on-demand employees

with no normally accepted rights such as sick-pay and overtime will give

employers at firms with more standard structures an incentive to cut

back. The more such pressures spread, the more protests against

“Plattform-Kapitalismus” the world is likely to see.

The on-demand economy will inevitably exacerbate the trend towards

enforced self-reliance that has been gathering pace since the 1970s.

Workers who want to progress will have to keep their formal skills up to

date, rather than relying on the firm to train them (or to push them up

the ladder regardless). This means accepting challenging assignments

or, if they are locked in a more routine job, taking responsibility for

educating themselves. They will also have to learn how to drum up new

business and make decisions between spending and investment.

At the same time, governments will have to rethink institutions that

were designed in an era when contract employers were a rarity. They will

have to clean up complicated regulatory systems. They will have to make

it easier for individuals to take charge of their pensions and health

care, a change which will be more of a problem for America, which ties

many benefits to jobs, than Europe, which has a more universal approach.

They will also have to encourage schools to produce self-reliant

citizens rather than loyal employees.

One of Gilbert and Sullivan’s oddest operettas, “Utopia Limited—or

the Flowers of Progress”, focuses on an exotic South Sea island which,

under the influence of Victorian industrialism, sets about turning all

the inhabitants into limited companies. It is rarely performed today, in

part because the targets of its on-the-nose-in-1893 satire seem remote.

But perhaps, after a century in which companies were vast things, such a

satire of corporate individualism is due for a revival or two. If so,

the piece will be easier than ever to stage: if there are not already

on-demand services that can provide Polynesian props, semi-retired set

designers and down-on-their-luck tenors at the swipe of a screen, there

soon will be.

Navalny tried to reach Manezh Square but was arrested before he could reach the rally

Navalny tried to reach Manezh Square but was arrested before he could reach the rally

Maria Alyokhina was jailed in 2012 for Pussy Riot's anti-Putin activism

Maria Alyokhina was jailed in 2012 for Pussy Riot's anti-Putin activism

Protesters remained on the streets as temperatures plummeted

A court has ruled that he will not face further sanctions for violating the terms of his detention.

Protesters remained on the streets as temperatures plummeted

A court has ruled that he will not face further sanctions for violating the terms of his detention. Protesters climbed into a huge Christmas ball, a street decoration near the Kremlin

Protesters climbed into a huge Christmas ball, a street decoration near the Kremlin

Dozens of people have been detained

Dozens of protesters, including well-known Russian bloggers,

members of the group Pussy Riot and other opposition activists, climbed

into a huge Christmas ball, a street decoration a few steps away from

the Kremlin wall.

Dozens of people have been detained

Dozens of protesters, including well-known Russian bloggers,

members of the group Pussy Riot and other opposition activists, climbed

into a huge Christmas ball, a street decoration a few steps away from

the Kremlin wall. Navalny released a selfie on the way to the rally

Upon arriving at the rally, police detained the opposition leader and drove him to his house in a police van.

Navalny released a selfie on the way to the rally

Upon arriving at the rally, police detained the opposition leader and drove him to his house in a police van. Navalny tried to reach Manezh Square but was arrested before he could reach the rally

Navalny tried to reach Manezh Square but was arrested before he could reach the rally

Maria Alyokhina was jailed in 2012 for Pussy Riot's anti-Putin activism

Maria Alyokhina was jailed in 2012 for Pussy Riot's anti-Putin activism

Protesters remained on the streets as temperatures plummeted

Protesters remained on the streets as temperatures plummeted

Protesters climbed into a huge Christmas ball, a street decoration near the Kremlin

Protesters climbed into a huge Christmas ball, a street decoration near the Kremlin

Dozens of people have been detained

Dozens of people have been detained

Navalny released a selfie on the way to the rally

Navalny released a selfie on the way to the rally

What we know so far

What we know so far Relatives 'were hoping for a miracle'

Relatives 'were hoping for a miracle'

Agony in Surabaya

Agony in Surabaya 'We do not know where the plane is'

'We do not know where the plane is'