Our endorsement

by Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit, London

Despite the risk on Europe, the coalition led by David Cameron should have a second term

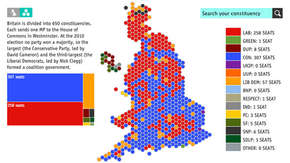

BRITAIN is a midsized island with outsized influence. Its

parliamentary tradition, the City’s global role, the union of England,

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, membership of the European Union

and a history of leading revolutions in economic policy mean that

British elections matter beyond Britain’s shores. But few have mattered

more than the one on May 7th, when all these things are at stake.

Though you would never know it from the campaigns’ petty squabbling, the country is heading for profound and potentially irrevocable change. The polls suggest that no combination of parties will win a stable majority—which could be the death knell for strong government (see article). May 7th could also mark the point of no return for the troubled union between England and Scotland, thanks to a surge in support for the secessionist Scottish National Party (SNP). The Tories have promised to renegotiate Britain’s relations with the EU and put the result to an in/out referendum on membership by the end of 2017. Meanwhile Ed Miliband, Labour’s leader, wants to remake British capitalism in pursuit of a fairer society. If he had his way, he would be the most economically radical premier since Margaret Thatcher.

Five years on, the choice has become harder. The Tories’ Europhobia, which we regretted last time, could now do grave damage. A British exit from the EU would be a disaster, for both Britain and Europe. Labour and the Liberal Democrats are better on this score. But such is the suspicion many Britons feel towards Brussels that a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU is probably inevitable at some point. And we believe that the argument can be won on its merits.

The Lib Dems share our welcoming attitude towards immigrants and are keen to reform the voting system. But they can at most hope to be the junior partner in a coalition. The electorate, and this newspaper, therefore face a choice between a Conservative-dominated government and a Labour-dominated one. Despite the risk on Europe, the better choice is Mr Cameron’s Conservatives.

Our decision is based on the economy, where the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition has a stronger record than many realise and where Labour poses a greater risk. Admittedly, the macroeconomic signals are mixed. The budget deficit, at 5% of GDP, is still the second-highest in the G7. As Britons consume more than they produce, the current-account deficit is a worrying 5.5% of GDP. And although employment is high, living standards have suffered and productivity is weak. Adjusted for inflation, wages have fallen every year since 2009.

The Tories have made this squeeze on British living standards more painful, particularly for young people. They have protected pensioners from budget cuts and showered them with tax giveaways, forcing bigger sacrifices elsewhere. A failure to boost housing supply has led to soaring prices, also hitting the young. Some of the Tories’ election promises—to spare houses worth up to £1m ($1.5m) from inheritance tax and to sell social housing at a discount—are economically indefensible vote-buying gestures that will only add to the unfairness.

But three things count in the Tories’ favour. The coalition has cut the deficit more pragmatically than it admits and more progressively than its critics allow. When the economy weakened, the Tories eased the pace (although not by as much as this newspaper would have liked). Though the poorest Britons have been hit hard by spending cuts, the richest 10% have borne the greatest burden of extra taxes. Full-time workers earning the minimum wage pay a third as much income tax as in 2010. Overall, inequality has not widened—in contrast to America.

The record on public services is good. Government spending has fallen from 45.7% of GDP in 2010 to 40.7%, yet public satisfaction with the police and other services has gone up. Although almost 1m public-sector jobs have been cut, Britain has a higher share of people in work than ever before. From extra competition in education (with new free schools and academies) to the overhaul of the benefits system, public services are being revitalised. Some innovations have failed, including a rejigging of the National Health Service (NHS), but Britain’s reform of the state has been energetic and promising.

And lastly, in the short term, Britain’s weak productivity is the corollary of a jobs-rich, squeezed-wage recovery. Wage stagnation, as our briefing explains (see article), is not an exclusively British malaise. It is also preferable, both in economic efficiency and social equity, to the French or Italian disease of mass joblessness. Better to recover from a financial crash and deep recession with a flexible labour market in which wages adjust than through unemployment. Britain will be a model for Europe if the Tories can boost productivity—and they aim to do so by improving schools and infrastructure, giving power and money to cities and investing in science.

Labour’s greater threat lies not in redistribution, but in meddling. Mr Miliband believes that living standards are squeezed because markets are rigged—and that the government can step in to fix them. He would freeze prices while “reviewing” energy markets, clamp down on the most flexible “zero-hour” labour contracts and limit rent rises. Along with this suspicion of private markets is an aversion to competition in the public sector, leading to proposals for, say, a cap on profit margins when private companies contract to provide services for the NHS.

Mr Miliband is fond of comparing his progressivism to that of Teddy Roosevelt, America’s trustbusting president. But the comparison is false. Rather than using the state to boost competition, Mr Miliband wants a heavier state hand in markets—which betrays an ill-founded faith in the ingenuity and wisdom of government. Even a brief, limited intervention can cast a lasting pall over investment and enterprise—witness the 75% income-tax rate of France’s president, François Hollande. The danger is all the greater because a Labour government looks fated to depend on the SNP, which leans strongly to the left.

On May 7th voters must weigh the certainty of economic damage under Labour against the possibility of a costly EU exit under the Tories. With Labour, the likely partnership with the SNP increases the risk. For the Tories, a coalition with the Lib Dems would reduce it. On that calculus, the best hope for Britain is with a continuation of a Conservative-led coalition. That’s why our vote is for Mr Cameron.

Though you would never know it from the campaigns’ petty squabbling, the country is heading for profound and potentially irrevocable change. The polls suggest that no combination of parties will win a stable majority—which could be the death knell for strong government (see article). May 7th could also mark the point of no return for the troubled union between England and Scotland, thanks to a surge in support for the secessionist Scottish National Party (SNP). The Tories have promised to renegotiate Britain’s relations with the EU and put the result to an in/out referendum on membership by the end of 2017. Meanwhile Ed Miliband, Labour’s leader, wants to remake British capitalism in pursuit of a fairer society. If he had his way, he would be the most economically radical premier since Margaret Thatcher.

A balance of risks

If the stakes are high, the trade-offs are uncomfortable, at least

for this newspaper. Our fealty is not to a political tribe, but to the

liberal values that have guided us for 172 years. We believe in the

radical centre: free markets, a limited state and an open, meritocratic

society. These values led us to support Labour’s Tony Blair in 2001 and

2005. In 2010 we endorsed David Cameron, the Tory leader, seeing in him a

willingness to tackle a yawning budget deficit and an ever-expanding

state.Five years on, the choice has become harder. The Tories’ Europhobia, which we regretted last time, could now do grave damage. A British exit from the EU would be a disaster, for both Britain and Europe. Labour and the Liberal Democrats are better on this score. But such is the suspicion many Britons feel towards Brussels that a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU is probably inevitable at some point. And we believe that the argument can be won on its merits.

The Lib Dems share our welcoming attitude towards immigrants and are keen to reform the voting system. But they can at most hope to be the junior partner in a coalition. The electorate, and this newspaper, therefore face a choice between a Conservative-dominated government and a Labour-dominated one. Despite the risk on Europe, the better choice is Mr Cameron’s Conservatives.

Our decision is based on the economy, where the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition has a stronger record than many realise and where Labour poses a greater risk. Admittedly, the macroeconomic signals are mixed. The budget deficit, at 5% of GDP, is still the second-highest in the G7. As Britons consume more than they produce, the current-account deficit is a worrying 5.5% of GDP. And although employment is high, living standards have suffered and productivity is weak. Adjusted for inflation, wages have fallen every year since 2009.

The Tories have made this squeeze on British living standards more painful, particularly for young people. They have protected pensioners from budget cuts and showered them with tax giveaways, forcing bigger sacrifices elsewhere. A failure to boost housing supply has led to soaring prices, also hitting the young. Some of the Tories’ election promises—to spare houses worth up to £1m ($1.5m) from inheritance tax and to sell social housing at a discount—are economically indefensible vote-buying gestures that will only add to the unfairness.

But three things count in the Tories’ favour. The coalition has cut the deficit more pragmatically than it admits and more progressively than its critics allow. When the economy weakened, the Tories eased the pace (although not by as much as this newspaper would have liked). Though the poorest Britons have been hit hard by spending cuts, the richest 10% have borne the greatest burden of extra taxes. Full-time workers earning the minimum wage pay a third as much income tax as in 2010. Overall, inequality has not widened—in contrast to America.

The record on public services is good. Government spending has fallen from 45.7% of GDP in 2010 to 40.7%, yet public satisfaction with the police and other services has gone up. Although almost 1m public-sector jobs have been cut, Britain has a higher share of people in work than ever before. From extra competition in education (with new free schools and academies) to the overhaul of the benefits system, public services are being revitalised. Some innovations have failed, including a rejigging of the National Health Service (NHS), but Britain’s reform of the state has been energetic and promising.

And lastly, in the short term, Britain’s weak productivity is the corollary of a jobs-rich, squeezed-wage recovery. Wage stagnation, as our briefing explains (see article), is not an exclusively British malaise. It is also preferable, both in economic efficiency and social equity, to the French or Italian disease of mass joblessness. Better to recover from a financial crash and deep recession with a flexible labour market in which wages adjust than through unemployment. Britain will be a model for Europe if the Tories can boost productivity—and they aim to do so by improving schools and infrastructure, giving power and money to cities and investing in science.

Statism masquerading as progressivism

Labour has a different way to tackle what it calls the “crisis” in

living standards. In fiscal terms, its agenda belongs to the moderate

centre-left. Mr Miliband also promises deficit reduction, and at a pace

that makes more macroeconomic sense than the Tories’ plan—though his

numbers are vaguer, and Labour’s record makes them harder to believe. He

proposes a bit more redistribution: Labour plans tax increases for the

wealthy, including raising the top rate of tax back to 50%, from 45%,

and imposing a “mansion tax” on houses worth more than £2m.

Individually, many of these proposals are reasonable. (The annual

mansion tax on a £3m London house would be only £3,000, a fraction of

the levy on New York property.) But, taken together, these plans risk

chasing away the most enterprising, particularly the footloose global

talent that London attracts.Labour’s greater threat lies not in redistribution, but in meddling. Mr Miliband believes that living standards are squeezed because markets are rigged—and that the government can step in to fix them. He would freeze prices while “reviewing” energy markets, clamp down on the most flexible “zero-hour” labour contracts and limit rent rises. Along with this suspicion of private markets is an aversion to competition in the public sector, leading to proposals for, say, a cap on profit margins when private companies contract to provide services for the NHS.

Mr Miliband is fond of comparing his progressivism to that of Teddy Roosevelt, America’s trustbusting president. But the comparison is false. Rather than using the state to boost competition, Mr Miliband wants a heavier state hand in markets—which betrays an ill-founded faith in the ingenuity and wisdom of government. Even a brief, limited intervention can cast a lasting pall over investment and enterprise—witness the 75% income-tax rate of France’s president, François Hollande. The danger is all the greater because a Labour government looks fated to depend on the SNP, which leans strongly to the left.

On May 7th voters must weigh the certainty of economic damage under Labour against the possibility of a costly EU exit under the Tories. With Labour, the likely partnership with the SNP increases the risk. For the Tories, a coalition with the Lib Dems would reduce it. On that calculus, the best hope for Britain is with a continuation of a Conservative-led coalition. That’s why our vote is for Mr Cameron.

No comments:

Post a Comment