All latest updates

by Suzanne Gould and Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit

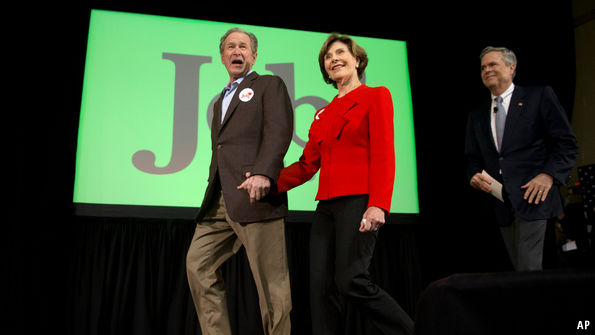

George W. Bush makes an appearance to support Jeb

The former president drags himself away from his oils to give his brother a push

That is one reason why this was his first public appearance, alongside his wife Laura and brother Jeb, in Jeb’s presidential campaign. Another was to mitigate the unpleasant whiff of dynasticism that clings to it; Jeb’s campaign coffers were filled by friends of the Bush brothers’ daddy, President George H.W. Bush, as were George W.’s coffers before him. A third reason was that George W., now happily retired to paint bad pictures and grow trees on his ranch, has become even more contentious during the primary contest, as his legacy, of military fiasco, lavish spending and a failed stab at immigration reform, has come under attack from Jeb’s rivals. At a Republican debate in South Carolina on February 13th Donald Trump accused George W. of wittingly invading Iraq on a false prospectus and failing to “keep America safe”—the phrase apologists for the discredited president are most likely to use in his defence.

But if his appearance in Charleston was in that sense inauspicious, it was justified as an act of desperation. Trounced in Iowa, only slightly redeemed in New Hampshire, Jeb!—as image consultants have branded him—needs at least to beat Marco Rubio, his main rival for the establishment vote, in South Carolina on February 20th if he is to avoid humiliation and abandonment by his father’s friends. His advisers believed that George W., whose own presidential ambitions were once saved by South Carolina and who is liked by its many ex-servicemen, might be the filip he needs. “Bush country,” they call the state.

There was noisy enthusiasm for the former president in the crowd—of a thousand or so white-haired pensioners, servicemen with buzz-cuts and proper-looking professionals, some with children. Most said they had come, on Presidents’ Day, mainly to see George W., not his brother. “He was my president when I enlisted,” said Joseph Beaudeg, a 30-year-old marine, who had brought his six-year-old daughter to “see a president”.“This is why we’re here,” said Rutledge Young, a lawyer, pointing to his discreet “W” lapel badge. Only a handful volunteered much enthusiasm for Jeb. Miranda Dobbins, a college administrator and Ted Cruz fan, was one of several who said they had not given him much thought.

What accounts for the brothers’ contrasting political fortunes? It is not all Mr Trump’s doing—though his ridiculing of Jeb as a “low-energy” dolt has been relentless and brilliant. (“I said, Why don’t you use the last name, you’ll do better—believe me, it’s better than exclamation points,” Mr Trump chipped in this week.) One explanation is that George W. is a much better retail politician than the wonkish former governor of Florida will ever be.

When “W” told an execrable joke about being a tree farmer (“It helps me practice my stump speech!”), it was almost funny; the crowd loved it. When Jeb! cracked a better gag—he claimed to have vetoed so much regulation in Florida that they called him Veto Corleone—no one laughed. In a rare serious remark—in a speech in which he did not deign to name any of his brother’s rivals—George W. declared himself proud to be a member of the reviled establishment. Yet with his blokeish manner, accident-prone English and earnest religiosity, he never seemed particularly like one. By contrast stiff, proper Jeb, though in some ways, including his bilingual household, less conventional than George W., seems like a man prone to wear chequered golfing slacks to unwind. That makes him, metaphorically speaking, not well-suited to America’s distempered electorate.

There was little reason, with the primary vote looming, to suppose George W.’s return from obscurity would fix that. The Bush brothers’ first instincts were right; if Jeb’s famous relatives may boost him with some voters, they will turn off others. Moreover, South Carolina is not really Bush country these days. The mixture of social conservatism and pro-business posturing that won the state for George W. in 2000 did not work for Mitt Romney, the Republican nominee in 2012. He lost South Carolina to the more acerbic Newt Gingrich, whose attacks on Washington found favour with anti-government Tea Partiers and disaffected working-class whites.

That both groups had suffered a crashing loss of confidence in steady-as-she-goes establishment conservativism was chiefly because of the economic and foreign policy calamities George W. presided over. And the suspicion and contempt they engendered endures, which is why all the mainstream Republican candidates—even more compelling ones than Jeb!—are now struggling. It was rather heart-warming to hear the nostalgic, faintly defiant cheers for George W. from a crowd of cautious, quietly prosperous Republicans who do not want a thuggish property tycoon to rip America up and make it great again. But the evidence suggests that W. played his main hand in this race years ago, and it has not turned out well.

No comments:

Post a Comment