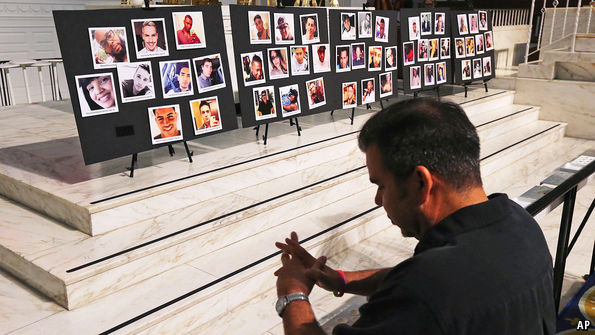

Aftermath of a tragedy

The right lessons to learn from a deadly massacre

It was also an early test of how a President Trump might handle a crisis if elected in November. One of the finest moments of George W. Bush’s presidency was when he went to an Islamic centre six days after 9/11 and issued a call for tolerance and unity. Mr Trump’s first thought was to exploit the shooting to score a point: “Appreciate the congrats for being right on radical Islamic terrorism,” he tweeted. It got worse. The Republican nominee first implied that the president might secretly be in league with Islamic State (IS). Then he gave a speech which suggested that American Muslims are a fifth column who “know what’s going on” but choose not to tell the police about impending attacks.

Aside from its jarring dissonance with the idea that the United States is a melting pot where everyone is American first, the speech was corrosive, because it sought to turn Americans against each other, and foolish, because America needs co-operation from Muslims at home and abroad to prevent attacks.

Seen another way, the attack was a crime motivated by a mixture of hatred against gay people with—judging by reports that Mr Mateen himself visited the club—an element of self-loathing. The speed at which most Americans have become tolerant of gay people is astonishing. In 2003 Florida still had a law against sodomy. Thirteen years later it was legal for the men and women at the Pulse nightclub not only to go home with whomever they pleased, but to marry them as well.

American Muslims are slightly more likely to support gay marriage than evangelical Christians are. But rapid social change always leaves some people behind. When America abandoned racial segregation, a small, fanatical group of white supremacists remained. Something similar may happen with gay Americans, who find their sexuality is met with indifference from parents, friends and colleagues, but with occasional, shocking acts of violence from bigoted strangers.

The silver bullet they won’t fire

Lastly, the shooting shows that America has a unique vulnerability to

lone-wolf attacks because of its gun laws. In France two people were

killed the day after the Florida attacks by a man who claimed

inspiration from IS. He wielded a knife. Armed with an assault-rifle and

a semi-automatic pistol he could have killed many more. In America Mr

Mateen was able to walk into a local gun store and buy everything he

needed to kill or wound 102 people, without breaking any law.Mass shootings do sometimes happen in countries with strict gun laws. But they are far more frequent in America, which has seen 37 incidents in which at least four people were killed in the past decade alone. These numbers do not take account of the more humdrum shootings that make the news only if someone famous is involved (the night before the shooting at Pulse a singer was shot dead in Florida by a fan) or if the victim is a child or a policeman.

Is it too much to hope that anything will change after this week’s carnage? Public support for tighter gun laws is high, but gun-owners are determined not to relinquish their weapons or to be prevented from buying more (see article). Polling suggests that most people with guns think that firearms make them and their families safer. They are impervious to statistics on accidental deaths of children. Even if gun purchases were banned tomorrow, about 300m firearms would remain.

After previous mass shootings, such as the one in Newtown, Connecticut, when 20 children died, Republican-controlled state legislatures passed looser gun laws. Florida’s state legislature has debated doing away with the state’s ban on guns in schools and colleges, on the ground that it is always safer to arm more people. The Orlando shooting ought to erode support for permissive gun laws. Sadly, experience suggests it is likely to have the opposite effect.

No comments:

Post a Comment