That Eighties show

Donald Trump’s attempt at Reaganomics will prove costlier than the original

FOR the moment, the policy priorities of the Trump administration-in-waiting are a basket of unknowables. Plans to scrap Obamacare or re-deregulate America’s financial sector, though dear to Republican hearts, are easier to champion on the campaign stump than to implement. A step away from globalism—Donald Trump’s most consistent campaign theme—could make for an awkward opening gambit given pockets of Republican resistance to overt protectionism. Tax cuts and infrastructure spending, on the other hand, look like an easy and unifying win for the new administration. And indeed, market moves since Mr Trump’s victory seem to imply an expectation of a Ronald Reaganesque turn in American fiscal policy; government-bond yields have risen, seemingly in expectation of bigger deficits, faster growth and higher inflation. Yet any resemblance that Mr Trump’s plans may bear to Reaganomics is as much a cause for concern as for optimism.

The president-elect’s tax proposals are easily the boldest since Reagan’s. Mr Trump’s plan would slash the highest marginal income-tax rates, cut rates of tax on corporate income and on capital gains, and eliminate federal inheritance and gift taxes entirely. According to an analysis by the Tax Policy Centre, a think-tank, the plan would reduce annual federal-tax revenue by about 4% of GDP. In contrast, in the first four years after its implementation the tax reform act of 1981 reduced annual revenue by almost 3% of GDP. At the same time, Mr Trump seems keen on new government spending; his transition-team website refers to $550bn in desired new infrastructure investment. Even if the legislation to emerge from Congress is more moderate, as seems likely, a big dose of tax cuts and new spending appears to be in the offing.

Stimulus would have its benefits. Higher inflation would be a welcome change from the spectre of deflation that until recently stalked the rich world. Some economists reckon that running the economy “hot”, to the extent that demand outstrips its productive potential, could nurture growth in America’s economic capacity: by bringing workers on the margins of the labour force back into employment, for example. Yet a Reaganomics rerun would almost certainly do more harm than good. The experience of the 1980s suggests three big causes for concern.

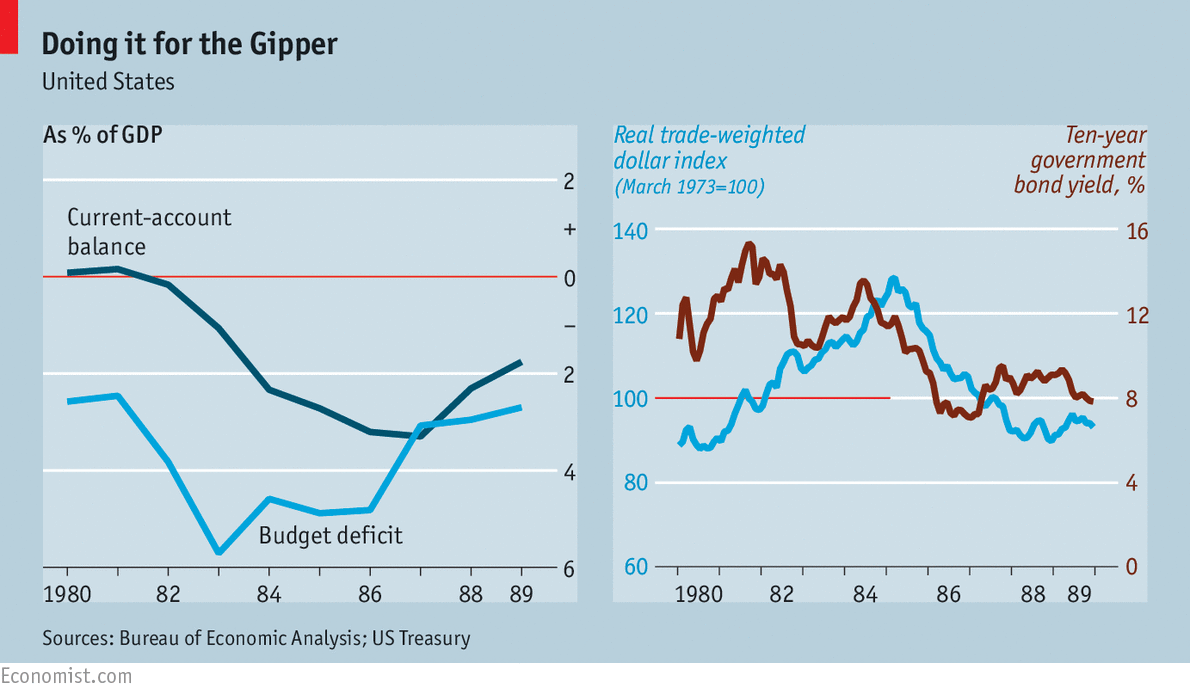

The first is financial instability. American interest rates in the 1980s were remarkably high: thanks initially to Paul Volcker’s efforts to bring down inflation, and later on to faster American growth and heavy government borrowing (see chart). High interest rates attracted money from abroad, pushing up the value of the dollar: it rose, on a trade-weighted basis, by roughly 40% from 1980 to 1985. As a result, developing economies, including many in Latin America, found themselves with unpayable dollar-denominated loans. Sovereign-debt woes crippled the affected countries’ economies; meanwhile, debt defaults and restructurings saddled big American banks with large losses, pushing some to the brink of insolvency. Today, most emerging economies hold far less dollar-denominated public debt. Yet vulnerabilities remain. The Federal Reserve has prepared markets for a gradual pace of monetary tightening. Should higher inflation convince the Fed that more interest-rate hikes are needed sooner, many investors in emerging markets could be caught off guard. A bout of chaotic capital flight could threaten shakier banks or induce governments to adopt capital controls. America, which eventually intervened to help manage the Latin American debt crisis, will probably be slower to lend a hand under Mr Trump.

Trumped-up trickle-down economics

American generosity might be in especially short supply as a result of a second side-effect of Trumpian Reaganomics. As the dollar soared in the early 1980s, America’s current account flipped from a small surplus into sizeable deficit. American firms howled. Efforts early in the 1980s to cajole trading partners into limiting exports gave way to more serious interventions later on. In 1985 James Baker, then treasury secretary, negotiated the Plaza accord with Britain, France, Japan and West Germany to bring down the value of the dollar. And in 1987 Reagan slapped economic sanctions on Japan for its failure to meet the terms of an agreement on trade in semiconductors.

Mr Trump, no instinctive free-trader, might face a similar dynamic. Faster growth and higher interest rates might attract foreign capital and place upward pressure on the dollar, which has indeed been rising since the election. That will help exporters to America and hamper a manufacturing revival in the struggling towns that helped Mr Trump win. In fact, the Mexican peso has fallen by about 10% against the dollar since the election, boosting the competitiveness of Mexican firms relative to their American counterparts. Yet Mr Trump will find responding to these shifts to be trickier than did Reagan. Sprawling supply-chains mean that punitive tariffs are less obviously useful to domestic firms than they once were. A battle over exchange rates between America and China could prove far more dangerous, both economically and geopolitically, than Mr Baker’s negotiations.

Perhaps most important is a third lesson: that the boost to growth provided by tax cuts and liberalisation need not be spread evenly across the economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment