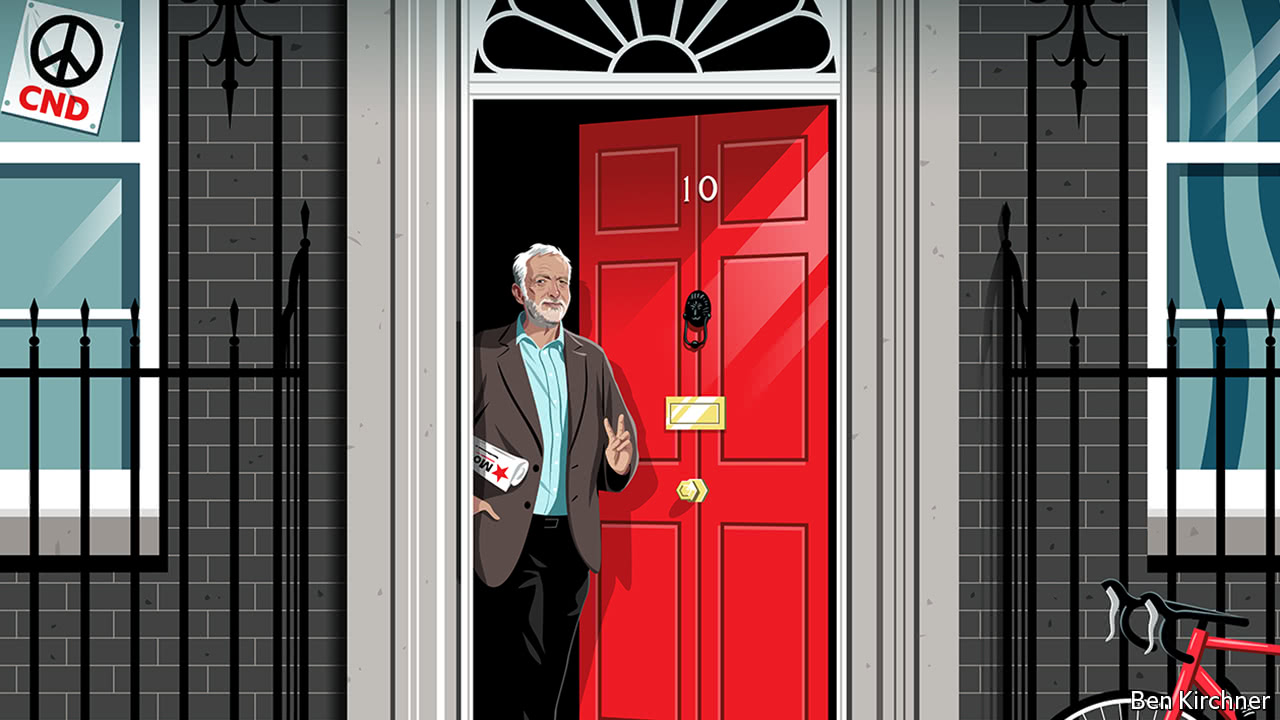

Jeremy Corbyn: Britain’s most likely next prime minister

Labour is on track to rule Britain. But who rules the Labour Party?

NOT even Jeremy Corbyn could quite picture himself as leader of the Labour Party when he ran for the job in 2015. After he became leader, few could see him surviving a general election. Now, with the Conservatives’ majority freshly wiped out and the prime minister struggling to unite her party around a single vision of Brexit (see Bagehot), the unthinkable image of a left-wing firebrand in 10 Downing Street is increasingly plausible. Bookmakers have him as favourite to be Britain’s next prime minister. Labour need win only seven seats from the Tories to give Mr Corbyn the chance to form a ruling coalition. He will be received at next week’s Labour Party conference as a prime minister in waiting.

There are two visions of a future Corbyn government. One, outlined in Labour’s election manifesto earlier this year, is a programme that feels dated and left-wing by recent British standards but which would not raise eyebrows in much of western Europe, nor do the country catastrophic harm. The other, which can be pieced together from the recent statements and lifelong beliefs of Mr Corbyn and his inner circle, is a radical agenda that could cause grave and lasting damage to Britain’s prosperity and security. The future of the Labour Party—and, quite probably, of the country—depends on which of these visions becomes reality.

But there is another plan for government, scattered among Mr Corbyn’s own statements, which would do serious and lasting harm (see article). Since becoming leader, he has called for a maximum wage as well as a minimum one. He has proposed “people’s quantitative easing”, under which the government would order the independent Bank of England to print money to fund public investments. Labour is committed to preserving Britain’s nuclear weapons: Mr Corbyn is disarmingly clear about his desire to scrap them. Though the party’s policy is to stay in NATO, Mr Corbyn has for decades called for it to disband; last year he refused to say whether, as prime minister, he would defend a NATO ally under attack from Russia.

Labour’s manifesto says that another independence referendum in Scotland is “unwanted and unnecessary”; Mr Corbyn has said it would be “fine”—which matters, because his most likely route to Downing Street would be with the support of the Scottish National Party. On Brexit, Labour is as hazy as the Tories. But its notional priority, access to the single market, is at odds with Mr Corbyn’s lifelong scepticism of globalisation in general and of the EU in particular.

All leaders must compromise with their parties. But it is rare for a leader’s personal views to contrast so strongly with those in his manifesto. Rarer still is the company Mr Corbyn keeps. Andrew Fisher, the main author of the manifesto, has previously argued for the nationalisation of all banks; Andrew Murray, a former Communist Party official who advised Mr Corbyn during the election, has defended the regime in North Korea. You can imagine how, surrounded by such people, Mr Corbyn would instinctively line up against America in a geopolitical emergency, and how he would see a financial crisis as Act One in the collapse of capitalism.

The party’s bureaucratic straitjackets are also loosening. Corbynites are now just about in the majority on Labour’s National Executive Committee, where their numbers will be strengthened by plans to appoint more trade unionists and ordinary members. The run-up to the conference has seen Corbynite candidates trouncing centrists in elections to committee chairmanships. Just as Tony Blair sidelined left-wing activists during the 1990s, Mr Corbyn is empowering them.

Labour’s half-million-odd members are fired up as never before, campaigning on foot and online. Most favour a more radical programme. A recent survey found that their priority was to move the party further to the left. One snag for Mr Corbyn is that they are overwhelmingly pro-EU; if he were sincere about the party being ruled by its members, not elites, he might agree at next week’s conference to advocate continued full membership of the single market. In practice, it seems that the views of ordinary members matter less than those of hard-core activists, who share Mr Corbyn’s Euroscepticism.

The most rapidly unravelling constraint on Mr Corbyn, however, is the opposition he faces. His cautious June manifesto was written as polls suggested that Labour could be wiped out. Now he stands with power in sight, facing a humiliated Conservative government. His room for manoeuvre expands by the week. June’s experiment with diluted Corbynism was a success. Expect the next dose to be stronger.

There are two visions of a future Corbyn government. One, outlined in Labour’s election manifesto earlier this year, is a programme that feels dated and left-wing by recent British standards but which would not raise eyebrows in much of western Europe, nor do the country catastrophic harm. The other, which can be pieced together from the recent statements and lifelong beliefs of Mr Corbyn and his inner circle, is a radical agenda that could cause grave and lasting damage to Britain’s prosperity and security. The future of the Labour Party—and, quite probably, of the country—depends on which of these visions becomes reality.

Latest updates

Good Corbyn, bad Corbyn

The manifesto launched this spring was insipid and backward-looking, dusting off tried and discarded ideas. But it would set Britain back years, not decades. The planned rise in corporation tax—a bad idea at a time when Brexit Britain needs to cling on to what business it can—would take the rate back only to its level in 2011. A proposed minimum wage of £10 ($13.50) per hour would be among the steepest in Europe, but not drastically higher than that planned by the Tories. Abolishing tuition fees would damage universities and mainly benefit the well-off, while nationalising the railways and some utilities would make them less efficient and starve them of investment. These are bad ideas, but not the policies to turn a country to rubble. If Labour combined them with an approach to Brexit that was less self-harming than that of the Tories—some of whom are still gunning for the kamikaze “no deal” outcome—its prospectus could even be the less batty of the two.But there is another plan for government, scattered among Mr Corbyn’s own statements, which would do serious and lasting harm (see article). Since becoming leader, he has called for a maximum wage as well as a minimum one. He has proposed “people’s quantitative easing”, under which the government would order the independent Bank of England to print money to fund public investments. Labour is committed to preserving Britain’s nuclear weapons: Mr Corbyn is disarmingly clear about his desire to scrap them. Though the party’s policy is to stay in NATO, Mr Corbyn has for decades called for it to disband; last year he refused to say whether, as prime minister, he would defend a NATO ally under attack from Russia.

Labour’s manifesto says that another independence referendum in Scotland is “unwanted and unnecessary”; Mr Corbyn has said it would be “fine”—which matters, because his most likely route to Downing Street would be with the support of the Scottish National Party. On Brexit, Labour is as hazy as the Tories. But its notional priority, access to the single market, is at odds with Mr Corbyn’s lifelong scepticism of globalisation in general and of the EU in particular.

All leaders must compromise with their parties. But it is rare for a leader’s personal views to contrast so strongly with those in his manifesto. Rarer still is the company Mr Corbyn keeps. Andrew Fisher, the main author of the manifesto, has previously argued for the nationalisation of all banks; Andrew Murray, a former Communist Party official who advised Mr Corbyn during the election, has defended the regime in North Korea. You can imagine how, surrounded by such people, Mr Corbyn would instinctively line up against America in a geopolitical emergency, and how he would see a financial crisis as Act One in the collapse of capitalism.

Paint the door red

The constraints on such wild behaviour are loosening. The first of those is the party’s MPs. Eight out of ten supported a motion of no confidence in their leader last year. Yet many wanted rid of Mr Corbyn mainly because they feared that he would lose them their jobs. With their majorities newly increased and power in sight, they have quietened down. Troublemakers can be threatened with deselection, and new parliamentary candidates vetted. Next week’s conference is expected to reduce the power of Labour MPs and MEPs.The party’s bureaucratic straitjackets are also loosening. Corbynites are now just about in the majority on Labour’s National Executive Committee, where their numbers will be strengthened by plans to appoint more trade unionists and ordinary members. The run-up to the conference has seen Corbynite candidates trouncing centrists in elections to committee chairmanships. Just as Tony Blair sidelined left-wing activists during the 1990s, Mr Corbyn is empowering them.

Labour’s half-million-odd members are fired up as never before, campaigning on foot and online. Most favour a more radical programme. A recent survey found that their priority was to move the party further to the left. One snag for Mr Corbyn is that they are overwhelmingly pro-EU; if he were sincere about the party being ruled by its members, not elites, he might agree at next week’s conference to advocate continued full membership of the single market. In practice, it seems that the views of ordinary members matter less than those of hard-core activists, who share Mr Corbyn’s Euroscepticism.

The most rapidly unravelling constraint on Mr Corbyn, however, is the opposition he faces. His cautious June manifesto was written as polls suggested that Labour could be wiped out. Now he stands with power in sight, facing a humiliated Conservative government. His room for manoeuvre expands by the week. June’s experiment with diluted Corbynism was a success. Expect the next dose to be stronger.

No comments:

Post a Comment