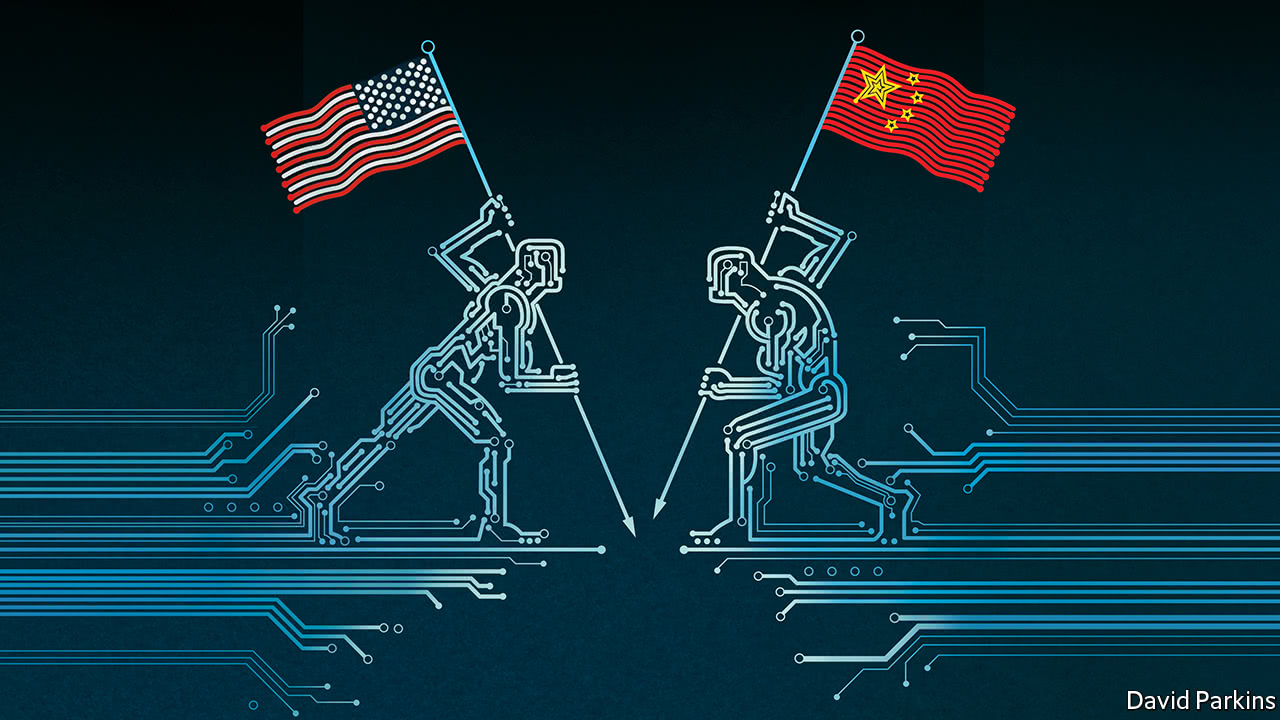

America v China

by Tamara Kachelmeier and Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit Technology Analysts, San Francisco

America’s technological hegemony is under threat from China

“DESIGNED by Apple in California. Assembled in China”. For the past decade the words embossed on the back of iPhones have served as shorthand for the technological bargain between the world’s two biggest economies: America supplies the brains and China the brawn.

Not any more. China’s world-class tech giants, Alibaba and Tencent, have market values of around $500bn, rivalling Facebook’s. China has the largest online-payments market. Its equipment is being exported across the world. It has the fastest supercomputer. It is building the world’s most lavish quantum-computing research centre. Its forthcoming satellite-navigation system will compete with America’s GPS by 2020.

America is rattled. An investigation is under way that is expected to conclude that China’s theft of intellectual property has cost American companies around $1trn; stinging tariffs may follow. Earlier this year Congress introduced a bill to stop the government doing business with two Chinese telecoms firms, Huawei and ZTE. Eric Schmidt, the former chairman of Alphabet, Google’s parent, has warned that China will overtake America in artificial intelligence (AI) by 2025.

This week President Donald Trump abruptly blocked a $142bn hostile takeover of Qualcomm, an American chipmaker, by Broadcom, a Singapore-domiciled rival, citing national-security fears over Chinese leadership in 5G, a new wireless technology. As so often, Mr Trump has identified a genuine challenge, but is bungling the response. China’s technological rise requires a strategic answer, not a knee-jerk one.

Yet it is one thing for a country to dominate televisions and toys, another the core information technologies. They are the basis for the manufacture, networking and destructive power of advanced weapons systems. More generally, they are often subject to extreme network effects, in which one winner establishes an unassailable position in each market. This means that a country may be squeezed out of vital technologies by foreign rivals pumped up by state support. In the case of China, those rivals answer to an oppressive authoritarian regime that increasingly holds itself up as an alternative to liberal democracy—particularly in its part of Asia. China insists that it wants a win-win world. America has no choice but to see Chinese technology as a means to an unwelcome end.

The question is how to respond. The most important part of the answer is to remember the reasons for America’s success in the 1950s and 1960s. Government programmes, intended to surpass the Soviet Union in space and weapons systems, galvanised investment in education, research and engineering across a broad range of technologies. This ultimately gave rise to Silicon Valley, where it was infused by a spirit of free inquiry, vigorous competition and a healthy capitalist incentive to make money. It was supercharged by an immigration system that welcomed promising minds from every corner of the planet. Sixty years after the Sputnik moment, America needs the same combination of public investment and private enterprise in pursuit of a national project.

Set against these standards, Mr Trump falls short on every count. The Broadcom decision suggests that valid suspicion of Chinese technology is blurring into out-and-out protectionism. Broadcom is not even Chinese; the justification for blocking the deal was that it was likely to invest less in R&D than Qualcomm, letting China seize a lead in setting standards.

Mr Trump has reportedly already rejected one plan for tariffs on China to compensate for forced technology transfer but only because the amounts were too small. Were America to impose duties on Chinese consumer electronics, for example, it would harm its own prosperity without doing anything for national security. An aggressively anti-China tack has the obvious risk of a trade tit-for-tat that would leave the world’s two largest economies both worse off and also more insecure.

Mr Trump’s approach is defined only by what he can do to stifle China, not by what he can do to improve America’s prospects. His record on that score is abysmal. America’s federal-government spending on R&D was 0.6% of GDP in 2015, a third of what it was in 1964. Yet the president’s budget proposal for 2019 includes a 42.3% cut in non-defence discretionary spending by 2028, which is where funding for scientific research sits. He has made it harder for skilled immigrants to get visas to enter America. He and some of his party treat scientific evidence with contempt—specifically the science which warns of the looming threat of climate change. America is right to worry about Chinese tech. But for America to turn its back on the things that made it great is no answer.

Not any more. China’s world-class tech giants, Alibaba and Tencent, have market values of around $500bn, rivalling Facebook’s. China has the largest online-payments market. Its equipment is being exported across the world. It has the fastest supercomputer. It is building the world’s most lavish quantum-computing research centre. Its forthcoming satellite-navigation system will compete with America’s GPS by 2020.

Latest stories

Why Vladimir Putin is sure to win the Russian election

Why China is swooping on Georgia’s airline industry

Asian and European cities compete for the title of most expensive city

Meet the Puteens

America sanctions Russians for election-meddling and cyber-attacks

Adam Smith, unlikely hero of the stage

This week President Donald Trump abruptly blocked a $142bn hostile takeover of Qualcomm, an American chipmaker, by Broadcom, a Singapore-domiciled rival, citing national-security fears over Chinese leadership in 5G, a new wireless technology. As so often, Mr Trump has identified a genuine challenge, but is bungling the response. China’s technological rise requires a strategic answer, not a knee-jerk one.

The motherboard of all wars

To understand what America’s strategy should be, first define the problem. It is entirely natural for a continent-sized, rapidly growing economy with a culture of scientific inquiry to enjoy a technological renaissance. Already, China has one of the biggest clusters of AI scientists. It has over 800m internet users, more than any other country, which means more data on which to hone its new AI. The technological advances this brings will benefit countless people, Americans among them. For the United States to seek to keep China down merely to preserve its place in the pecking order by, say, further balkanising the internet, is a recipe for a poorer, discordant—and possibly warlike—world.Yet it is one thing for a country to dominate televisions and toys, another the core information technologies. They are the basis for the manufacture, networking and destructive power of advanced weapons systems. More generally, they are often subject to extreme network effects, in which one winner establishes an unassailable position in each market. This means that a country may be squeezed out of vital technologies by foreign rivals pumped up by state support. In the case of China, those rivals answer to an oppressive authoritarian regime that increasingly holds itself up as an alternative to liberal democracy—particularly in its part of Asia. China insists that it wants a win-win world. America has no choice but to see Chinese technology as a means to an unwelcome end.

The question is how to respond. The most important part of the answer is to remember the reasons for America’s success in the 1950s and 1960s. Government programmes, intended to surpass the Soviet Union in space and weapons systems, galvanised investment in education, research and engineering across a broad range of technologies. This ultimately gave rise to Silicon Valley, where it was infused by a spirit of free inquiry, vigorous competition and a healthy capitalist incentive to make money. It was supercharged by an immigration system that welcomed promising minds from every corner of the planet. Sixty years after the Sputnik moment, America needs the same combination of public investment and private enterprise in pursuit of a national project.

Why use a scalpel when a hammer will do?

The other part of the answer is to update national-security safeguards for the realities of China’s potential digital threats. The remit of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), a multi-agency body charged with screening deals that affect national security, should be expanded so that minority investments in AI, say, can be scrutinised as well as outright acquisitions. Worries about a supplier of critical components do not have to result in outright bans. Britain found a creative way to mitigate some of its China-related security concerns, by using an evaluation centre with the power to dig right down into every detail of the hardware and software of the systems that Huawei supplies for the telephone network.Set against these standards, Mr Trump falls short on every count. The Broadcom decision suggests that valid suspicion of Chinese technology is blurring into out-and-out protectionism. Broadcom is not even Chinese; the justification for blocking the deal was that it was likely to invest less in R&D than Qualcomm, letting China seize a lead in setting standards.

Mr Trump has reportedly already rejected one plan for tariffs on China to compensate for forced technology transfer but only because the amounts were too small. Were America to impose duties on Chinese consumer electronics, for example, it would harm its own prosperity without doing anything for national security. An aggressively anti-China tack has the obvious risk of a trade tit-for-tat that would leave the world’s two largest economies both worse off and also more insecure.

Mr Trump’s approach is defined only by what he can do to stifle China, not by what he can do to improve America’s prospects. His record on that score is abysmal. America’s federal-government spending on R&D was 0.6% of GDP in 2015, a third of what it was in 1964. Yet the president’s budget proposal for 2019 includes a 42.3% cut in non-defence discretionary spending by 2028, which is where funding for scientific research sits. He has made it harder for skilled immigrants to get visas to enter America. He and some of his party treat scientific evidence with contempt—specifically the science which warns of the looming threat of climate change. America is right to worry about Chinese tech. But for America to turn its back on the things that made it great is no answer.

No comments:

Post a Comment