by Biodun Iginla, Political News Analyst, The Economist and BBC News, New York

What does Hillary stand for?

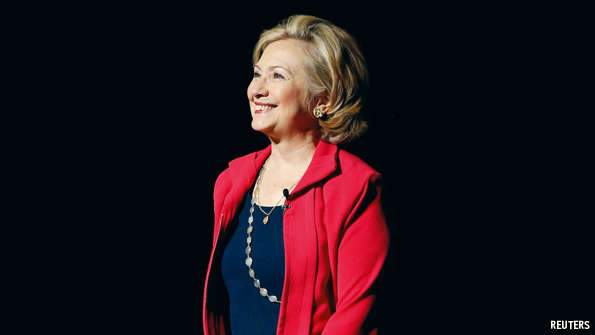

The most familiar candidate is surprisingly unknown

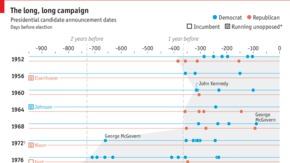

Steady on. The last time she seemed inevitable, she turned out not to be. The month before the Iowa caucuses in 2008, she was 20 points ahead of other Democrats in national polls, yet she still lost to a young senator from Illinois. She is an unsparkling campaigner, albeit disciplined and diligent. This time, no plausible candidate has yet emerged to compete with her for the Democratic nomination, but there is still time. Primary voters want a choice, not a coronation (see article). And it is hard to say how she would fare against the eventual Republican nominee, not least since nobody has any idea who that will be. The field promises to be varied, ranging from the hyperventilating Ted Cruz to the staid Jeb Bush. Rand Paul, a critic of foreign wars and Barack Obama’s surveillance state, joined the fray on April 7th (see article). Still, Mrs Clinton starts as the favourite, so it is worth asking: what does she stand for?

Air miles and briefing books

Competence and experience, say her supporters. As secretary of state,

she flew nearly a million miles and visited 112 countries. If a foreign

crisis occurs on her watch, there is a good chance she will already

have been there, read the briefing book and had tea with the local power

brokers. No other candidate of either party can boast as much.She also understands Washington, DC, as well as anyone. For eight years she was a close adviser to a president (her husband) who balanced the budget and secured bipartisan agreements to reform welfare and open up trade in North America. Afterwards, as a senator, Mrs Clinton made a habit of listening to, and working with, senators on both sides of the aisle, leading some Republicans publicly to regret having disliked her in the past. A President Hillary Clinton could be better at hammering out deals with lawmakers (of both parties) than President Obama has been. She would almost certainly try harder.

But to what end? For someone who has been on the national stage for a quarter-century, her beliefs are strangely hard to pin down. On foreign policy, she says she is neither a realist nor an idealist but an “idealistic realist”. In a recent memoir, she celebrates “the American model of free markets for free people”. Yet to a left-wing crowd, she says: “Don’t let anybody tell you, that, you know, it’s corporations and businesses that create jobs.” (An aide later said she meant tax breaks for corporations.) Some candidates’ views can be inferred from the advisers they retain, but Mrs Clinton has hundreds, including luminaries from every Democratic faction. Charles Schumer, her former Senate colleague from New York, called her “the most opaque person you’ll ever meet in your life”.

Mrs Clinton’s critics on the right fret that she is a power-hungry statist. (“Give her an inch and she’ll be your ruler,” warns a campaign badge.) On the left they fear that she is close to Wall Street (her campaign is predicted to raise $1 billion), divorced from the lives of ordinary Americans (she first moved into a governor’s mansion in 1979) and hawkish (she backed the invasion of Iraq). Perhaps she is something in between: a sensible moderate? She fits this bill better than, say, Elizabeth Warren or Martin O’Malley, two possible Democratic rivals who bash trade and banking. But voters need to know more.

The last time Mrs Clinton set out a detailed economic plan, during the 2008 campaign, she placed herself a little to the left of her husband in the 1990s (less keen on trade deals, for example) and quite close to where Mr Obama has ended up (indeed, Obamacare resembles her plan more than his). The world has since changed, and Democrats are furiously divided over how to ease inequality without constricting growth (see article). The Centre for American Progress, one of the think-tanks Mrs Clinton listens to, recently released a list of policies to promote what it calls “inclusive capitalism”. This contains lots of sensible stuff, such as boosting investment in infrastructure and expanding wage subsidies for hard-up workers; some intriguing ideas, such as encouraging “works councils” to bring labour and management together; and some dubious ones, such as ramping up implied subsidies for mortgages and creating make-work schemes for the young. How much of this would Mrs Clinton favour? Some details would be nice.

On foreign policy, Mrs Clinton’s pitch is that she would be tougher than Mr Obama. She backed his surge of troops in Afghanistan but regretted the expiry date he put on it. She urged him to arm the non-Islamist rebels in Syria; he dithered. She chides him for failing to find a better organising principle for foreign policy than “Don’t do stupid stuff.” Yet she leaves many details unfilled. For example: does she think she could have struck a better nuclear deal with Iran? Nonetheless, many foreigners would welcome an American commander-in-chief who is genuinely engaged with the world outside America.

Secrecy and privilege

Sceptics raise two further worries about Mrs Clinton. Some say she is

untrustworthy—a notion only reinforced by the revelation that she used a

private server for her e-mails as secretary of state, released only the

ones she deemed relevant and then deleted the rest. The other worry,

which she cannot really allay, is that dynasties are unhealthy, and that

this outweighs any benefit America might gain from electing its first

female president. Gary Hart, a former presidential candidate, told Politico

that, with more than 300m people in America, “We should not be down to

two families who are qualified to govern.” The campaign has barely

begun, but if Mrs Clinton is to deserve the job she desires, she has

questions to answer.

No comments:

Post a Comment