A plug for the battery

Virtual reality and artificial intelligence are not the only technologies to get excited about

IT IS more than two-and-a-half centuries since Benjamin Franklin grouped a number of electrically charged Leyden jars together and, using a military term, called them a “battery”. It is 25 years since Sony released a commercial version of the rechargeable lithium-ion battery, which now sits snugly in countless smartphones, laptops and other devices. In an era of robots and drones, artificial intelligence and virtual reality, the lithium-ion battery lacks futuristic glamour. Its deficiencies are quotidian and clear: witness the scrum of people around charging stations at airports. Yet few areas of technology promise as great an impact in as short a time.

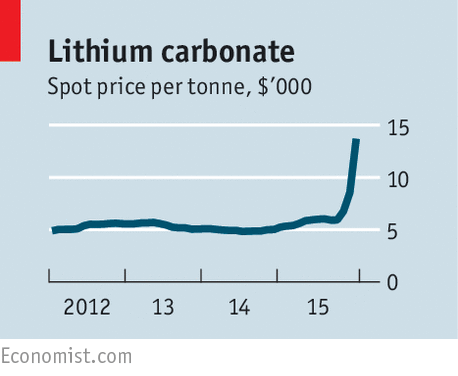

Increasingly, lithium-ion batteries are vaulting out of pockets into power tools, vehicles, homes and even power stations. Carmakers in America, China and Japan are rushing to secure supplies of lithium to prepare for a more electric future (see article). Such is the scramble, that the metal, used in small quantities in each battery cell, today is one of the world’s only hot commodities. The price of lithium carbonate imported to China more than doubled in the last two months of 2015.

Until now, the limits on the use of batteries have been storage capacity, cost and recharging times. But large-scale production is overcoming these hurdles. The head-turner at this week’s Detroit motor show was not a car but a battery—that of the 2017 Chevrolet Bolt, which General Motors’ boss, Mary Barra, said had “cracked the code” of combining long range with an affordable price. Tesla, an electric-car maker, is promising to start mass production of lithium-ion batteries this year in a giant “gigafactory” in Nevada. BYD, a Chinese rival, is hot on its heels. In ten months last year Chinese firms sold more electric vehicles than Tesla has since 2008. A further emphasis on batteries is a big part of China’s 2016-20 five-year plan.

Rising power

Electric cars are not the only source of demand. Batteries are also playing an increasingly important role in providing cleaner power on and off electricity grids. In South Africa, Australia, Germany and America, Tesla this year will start selling a $3,000 Powerwall for homeowners to store the solar energy from their roofs. Utilities are going even further. They are installing millions of lithium-ion battery cells into power plants to regulate supply at times of peak demand, and when it fluctuates because of intermittent wind and solar energy. California has ordered its electricity firms to offer 1.3 gigawatts (GW) of non-hydroelectric storage capacity within five years. That compares with total American power generation of more than 1,000GW, but is still more than double the 0.5GW of batteries plugged into grids around the world today. In 2016 a solar plant equipped with batteries will be installed in Hawaii, promising power after sunset at prices cheaper than diesel.

There is still a long way to go. As yet lithium-ion batteries do not have the capacity to store grid-scale power for more than a few hours. Costs are still too high; and the recent price spike in lithium will encourage researchers beavering away on other types of battery. Yet the more cells that are made, the more understanding and performance improve. Rising demand and higher prices will eventually also generate more lithium supply. Increasingly, lithium is becoming to batteries what silicon is to semiconductors—prevalent, even among worthy alternatives. In one form or another, the lithium-ion battery is the technology of our time.

No comments:

Post a Comment