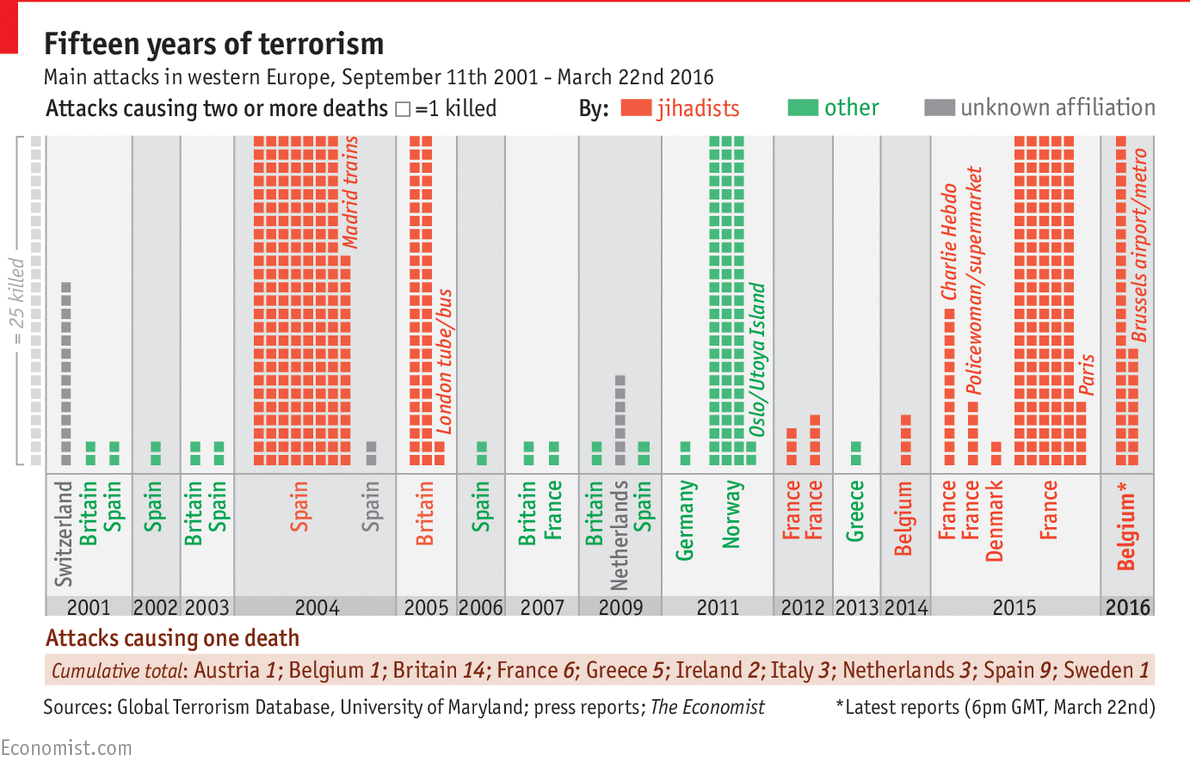

The Brussels attacks show that Islamic State is still growing in ambition and capability

Europe must confront the possibility of such attacks on a regular basis

BELGIUM’S satisfaction at finding Salah Abdeslam, the man believed to have been the Islamic State (IS) logistics chief behind the Paris terror attacks, which took the lives of 130 people four months ago, was always likely to be fleeting. That it had taken so long to track Mr Abdeslam down was worrying. That he was found staying in the apartment of a friend’s mother in Molenbeek, the district of Brussels that is probably home to the highest concentration of jihadist sympathisers in Europe, is an indication of chronic intelligence failure on the part of Belgian’s State Security Service and the police.

But perhaps the biggest worry is the discovery that IS's network in Belgium, and perhaps across Europe, is so extensive. To be able to conduct serial complex attacks—such as the multiple bombings in Brussels’ international airport and metro system, which killed at least 30 people on the morning of March 22nd—suggests IS can draw on perhaps hundreds of supporters, some of whom have reliable bomb-making expertise and know how to communicate securely.

Some will argue that the timing of the attacks on Brussels, coming so soon after the arrest of Mr Abdeslam, is a coincidence. But that probably underestimates the scale of the IS operation in Belgium. Indeed, Mr Abdeslam’s arrest may well have been the trigger for another cell to go into action with a plan that had been some weeks or months in preparation.

There are still hopes that Mr Abdeslam’s arrest and almost certain extradition to France will yield information that fills in the gaps in what is known about the Paris and Brussels attacks. But what has been learned so far by French investigators after the interrogation of witnesses and investigation of both the crime scenes and places where the terrorists had lived is disturbing enough.

An overriding concern is the extent of the network across Europe that IS appears to have been building for at least the past three years as a platform for sustaining a series of major terrorist outrages in different cities. There are known to be 18 people being held in six countries who are suspected of helping the Paris attackers. That is likely to be only the tip of the iceberg.

Intelligence services are faced with a lethal combination: thousands of European citizens radicalised on the internet and drawn to IS by its military and propaganda successes; battle-hardened fighters returning from Syria and Iraq who have received expert training; and the opportunities to infiltrate back into Europe unnoticed amid the huge flows of genuine refugees.

French investigators have also been taken aback by the sophistication of the IS external operations wing. It appears from the traces left by the Paris suicide bombers that IS bomb-makers in Europe have mastered manufacturing explosive devices that use triacetone triperoxide, known as TATP, whose precursors can be found in easily available products such as nail polish remover and hair lighteners. Making multiple TATP devices that detonate reliably requires a good deal of skill, but police have yet to locate either a bomb factory or any of the bomb-makers, some of whom are likely to have been sent directly from Iraq or Syria.

Another sign of their competent tradecraft is the discipline of their communications security. The French authorities had no clue of what was to unfold on the evening of November 13th and there seems to have been no actionable intelligence before the attacks earlier today, despite warnings from the Belgian interior minister that more attacks were likely. Sim cards taken from “burners” (pre-paid mobile phones that are used only once before being discarded) show no evidence of text messaging, e-mails or chat-room use. The conclusion is that the terrorists are using encryption for all their electronic communication, but precisely what kind may still not be known.

Finally, it increasingly looks as if IS operational planning always aims at carrying out multiple, sequenced attacks to spread confusion and to stretch the ability of emergency services to respond. Over the weekend, there were reports that London’s police and the army’s SAS special forces are now working on the possibility that the capital could be hit by up to 10 attacks, all occurring on the same day. It is also clear that such attacks will be against soft targets with the aim of causing as many casualties as possible.

Europe now has to confront the possibility that IS has acquired the capability to make devastating attacks on what amounts to a fairly regular basis. Yet faced with such a threat, it is still far from certain that Europe can react in the way that America did in the aftermath of September 11th 2001, when it was quickly understood that the failure of different agencies to pool and share intelligence had been instrumental in allowing the plot to proceed. America’s long run of preventing another foreign-borne attack on its soil is an indication of how well the lessons were learned. In Britain too, with its experience of combating IRA terrorism for decades, the security agencies and the police have shown how it should be done.

But to replicate that example across all the countries of the European Union is a tall order, even though the open borders of the Schengen passport-free zone should have suggested the need for joined-up intelligence long ago. In Belgium itself, politically riven between two language groups, inter-agency co-operation is known to be dire. Europol, the law-enforcement agency of the EU, does a useful job in facilitating information exchange and analysis. But it has no executive powers to carry out investigations and has an annual budget of around €100m ($112m).

The threat from IS is belatedly forcing national intelligence agencies to co-operate in ways they have not previously done, but there is a huge range in capabilities and IT systems, some pretty antiquated, that cannot yet share data effectively. Another question that may need to be answered at the European level is whether mass data collection on the American model is acceptable in terms of privacy and human rights. Having lived under Nazi and communist totalitarian states, Germans, in particular, are deeply opposed to the notion of the surveillance state.

No doubt, the political imperative to be seen to be doing something will result in some improvements in Europe’s ability to foil mass terror attacks. It may also be that as IS experiences further defeats on the battlefields of Iraq and Syria (it has lost about 40% of the territory it held in the former and about 15% in the latter), some of its sheen will disappear and it will no longer be a magnet for every budding jihadist. But for now, the flaws in Europe’s security remain gaping, while IS shows every sign both of increasing ambition and the capability to go with it.

6.50pm London: This piece has been updated with a new figure for the number of fatalities

No comments:

Post a Comment