by Susan Kumar and Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit, New Delhi

A $101m bank heist unseats the governor of Bangladesh’s central bank

Online thieves used fake emails to steal the money

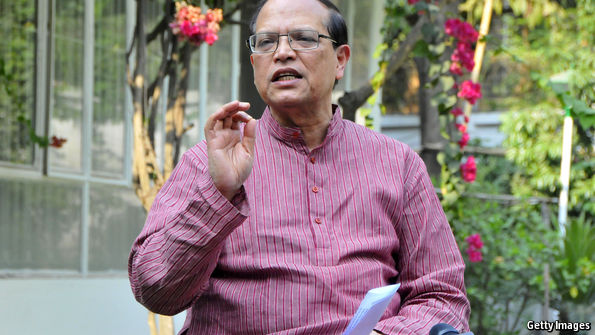

IT WAS as audacious as any heist, and yet unlikely material for a Hollywood blockbuster. Hackers masquerading as officials from Bangladesh’s central bank asked the New York branch of the Federal Reserve to transfer nearly $1 billion to private bank accounts in Sri Lanka and the Philippines. By the time authorities cottoned on, $101m had been nicked. On March 15th Atiur Rahman, the governor of Bangladesh’s central bank, took the blame and resigned.

That has not stopped the finger-pointing. In the manner of a bank customer complaining about fraudulent credit-card charges, Bangladeshi authorities say the Fed, which was acting as the central bank’s bank, should not have paid out anything at all. The Fed says the instructions it received were legitimate. The Philippine authorities cannot say what happened to the $81m sent to their country. Much of the money disappeared in its opaque casinos, which they say are not covered by anti money-laundering rules (a worry in itself). The CCTV system at a bank branch where some of the money was withdrawn was not working.

Even the criminals (of which basically nothing is known) should kick themselves: were it not for a typo in one of their requests, dozens more payments might have gone through. Staff at the central bank of Sri Lanka, who blocked a $20m onward transfer on the grounds that it was odd for a central bank to be making a big payment to a private account, covered themselves in glory. Deutsche Bank, which reportedly spotted a payment to a “fandation” and asked for a clarification, also comes out looking vigilant.

Mr Rahman, a development economist who was due to retire this summer, admits he is “not a technical guy”. It was as much his delay admitting the fraud—the finance minister claimed he first read about it in the papers—as the loss itself that made his position untenable.

The attack is hardly a one-off. Criminal gangs are adept at hacking into e-mail accounts and sending instructions to bankers asking them to wire large sums. Corporate treasurers are now warned not to trust e-mails that appear to come from the boss, requesting that a payment be made.

Kaspersky Lab, a cyber-security firm, last year claimed $1 billion had been siphoned from financial institutions in this way. The Bank of England said it faced “advanced, persistent and evolving cyber threats”. If a brave producer does take on the story of the Dhaka caper, expect plenty of sequels.

No comments:

Post a Comment