Young aborigines

Abuses at a juvenile prison prompt a national inquiry

WHEN he announced plans on July 25th to strengthen Australia’s anti-terrorism laws, Malcolm Turnbull, the prime minister, declared that his administration’s “primary duty” was to keep citizens safe. Within hours Australians were watching videos of government employees doing harm. Inmates of a youth detention centre at Darwin, in the Northern Territory, most of them indigenous children, were shown being thrown on floors, manacled, stunned with tear gas and subjected to other cruel treatment by prison guards. Dylan Voller, then aged 17, was left alone in a cell for two hours after guards had tied his arms, feet and head to a metal chair and put a hood over his face.

The prison videos were shown on “Four Corners”, an Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) programme. Mr Turnbull said he was “shocked and appalled” and announced a royal commission inquiry to “expose the culture that allowed it to occur and allowed it to remain unrevealed for so long”.

In fact, lawyers and indigenous leaders have long called for government action to cut Australia’s high rate of aboriginal youth imprisonment. Mick Gooda, an aboriginal official at the Australian Human Rights Commission, calls it “one of the most challenging human-rights issues facing our country”. The Northern Territory, a federal dependency, has one of the worst records. Indigenous people are almost a third of the territory’s population, compared with 3% for Australia as a whole. But they account for 96% of youngsters aged between 10 and 17 in detention. Amnesty International reported last year that the number of indigenous young people in detention in the territory nearly doubled over the four years to 2014.

Nationwide, Amnesty says young indigenous Australians are 26 times more likely to be in detention on an average night than their non-indigenous counterparts. It says governments have failed to respond to a “national crisis”. The exposure of the territory’s prison footage, recorded over the past six years, seems to bear this out. Lawyers and journalists had unsuccessfully sought the footage under freedom-of-information laws; whistle-blowers apparently enabled the ABC finally to reveal it. Yet Adam Giles, the territory’s chief minister, claimed he had not seen it before. He blamed a “culture of cover-up”. He could have added blame-shifting. Nigel Scullion, Mr Turnbull’s minister for indigenous affairs, “assumed” the territory government was handling the problem: “It did not pique my interest.”

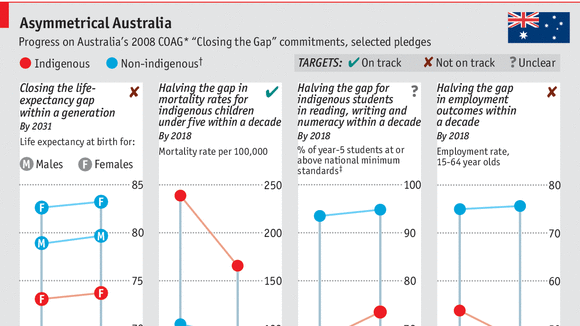

The high detention rates echo broader problems: indigenous Australians are poorer, unhealthier and do worse in school than their compatriots. Eight years ago, the federal and state governments set targets for “closing the gap” with the rest of the country. The scheme’s latest report says two crucial areas, jobs and life expectancy, are “not on track”. Some lawyers blame governments for spinning “law and order” as a quick fix although locking up young people often sets them back even more.

Mr Voller was first detained when he was 11 years old. Now 18, he is in an adult prison and is due for release this year. Gillian Triggs, head of the human rights commission, says it is “not too extreme” to compare his treatment to that of prisoners in Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq war.

Some want the inquiry to cover youth detention centres around Australia. Mr Turnbull will keep it “focused” on those in the Northern Territory; he wants it to report early next year. It will need to be more productive than another inquiry carried out 25 years ago, into high death-in-custody rates among indigenous people. Since then, says Mr Gooda, “our people are more likely than ever to be incarcerated.”

No comments:

Post a Comment