Why Nice was an unsurprising location for a terrorist attack

The idyllic Mediterranean beach town has a severe problem of Islamist radicalisation

AMONG the distressing questions that crowd the French consciousness after the latest terrorist horror, one of the more familiar is: why France? This was the third major attack on French soil since the Charlie Hebdo killings in January 2015, and the bloodiest ever in France after the Bataclan murders of November last year. It is hard for many French to understand why their country has suffered so much more than others in Europe. But this latest attack raises an even more puzzling question: why Nice?

With its ornate churches and palm-tree-fringed beaches, Nice is best known as a tourist destination. Less well-known is the fact that it faces one of France’s most intractable problems of Islamic radicalisation outside the Paris region. French news reports have named the suspect in Thursday’s atrocity as Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, a French citizen of Tunisian origin—and a resident of the city he attacked.

By the start of this year, at least 55 residents of Nice and other towns in the department of Alpes-Maritimes, which covers the Côte d’Azur, had left to fight in Syria or Iraq. That included 11 members of a single family. The department’s government recently closed down five underground prayer houses suspected of preaching violent Islamism. (In total there are roughly 40 mosques in and around Nice.) Increasingly worried about the flow of jihadists, Alpes-Maritimes was one of the first departments to put in place an early-warning system for families, schools and local services to try to prevent them from leaving for Syria, and to refer individuals at risk of radicalisation to specialist units.

Like most big cities in France, Nice has a big Muslim population; several were killed in the lorry attack. Concentrated in the tower blocks that fill the steep inland valleys a short drive from the coast, the neighbourhoods supply a share of ready young minds on which local jihadist recruiters prey. One in particular, Omar Omsen, also known as Omar Diaby, was well known to the local intelligence services and was thought to have been killed in Syria last year—although recent reports suggest that he is still alive, and may have faked his death.

It remains to be seen whether Omsen has any links to the perpetrator of the latest attack, but he certainly established an efficient centre of jihadism in the city. Born in Senegal, but raised on a housing estate in the suburb of Ariane, he was believed to have been behind the recruitment of the 11-member family who travelled to Syria from Nice. Linked to Jabhat al-Nusra, the al-Qaeda-linked group in Syria and rival to Islamic State, Omsen specialised in French propaganda videos, many of which proved popular on YouTube.

Last year, in a separate case, two teenage boys were taken off a plane at Nice airport before take-off, after the authorities received an alert that they were heading for jihad. In yet another case, a mother tried to bring a lawsuit against the French state for failing to stop her 16-year-old son leaving Nice airport for Syria, via Turkey, along with three others from the city. Yet another jihadist cell, known as Cannes-Torcy (dismantled by the police between 2012 and 2014), specifically targeted Nice. A returnee from Nice who had spent 16 months in Syria was arrested shortly after returning to France in January 2014. It is understood that he had been sent back to carry out a suicide bombing, at a time when no such attack had yet been carried out on French soil.

Faced with this spread of radicalism, the Alpes-Maritimes department has been at the forefront of French efforts to fight it. It has set up a special counter-radicalisation cell, with weekly meetings to analyse the alerts it receives from teachers, social workers, policemen and prison officers, all of whom have been trained by psychologists and others to look for signs of radicalisation. Since 2014, the department has recorded 522 such alerts, including 120 concerning youth under the age of 18.

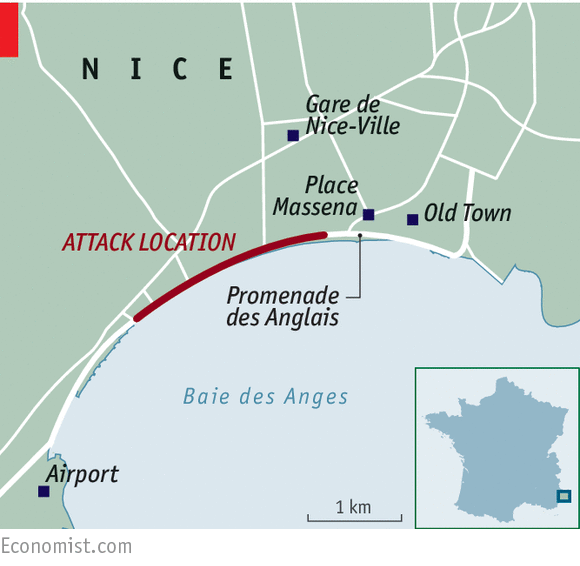

Officials in the department were particularly concerned about public security earlier this year, when Nice held its annual carnival—a parade of festive floats along the Promenade des Anglais, where the latest attack took place (see map above). The route was sealed off with roadblocks and panels of temporary walling to allow access only to spectators with tickets. There was much relief at the time when all went safely.

Such outdoor events have been the main security worry for France this year, in particular during the Euro 2016 football tournament, which concluded on July 10th without any attacks. But intelligence officials have continued to warn that crowded places, such as shopping centres and public transport, are vulnerable. The latest attack proved them cruelly right. The French government has now announced that the national state of emergency will be extended once again. Introduced after last November’s attacks, it was due to expire in July, but will now continue until October 26th. An emergency response is now becoming, in France, a chillingly permanent state of full alert.

No comments:

Post a Comment