A splintering headache

All latest updatesWeak winners and populist upstarts in Berlin’s election

THE big story of recent elections in German states has been the rise of the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD), on the far right of the political spectrum. The vote for Berlin’s assembly on September 18th was no exception: the AfD did well again, capturing 14.2% of the vote. It will enter the Berlin parliament for the first time, and is on track to win seats in the Bundestag in next year’s federal election.

But perhaps the bigger change is more subtle: Germany is witnessing the end of an era in which two big-tent parties dominated the political spectrum, one on the centre-right and the other on the centre-left. Henceforth Germany will have a six-party system that will see varying and colourful coalitions. And though progressively weakened by the backlash against her welcoming stance towards refugees, Angela Merkel, the chancellor, remains Germany’s dominant political force.

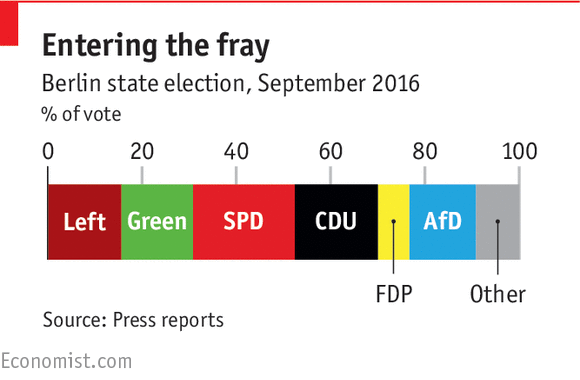

AfD’s success in Berlin was some way from its bigger successes, such as the 20.8% it won earlier this month in the eastern state of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. What is striking, though is that the ostensible “winners”—the Social Democrats, who came in first with 21.6% of the vote—scored the worst of any first-place finish in post-war German history (see chart). Their coalition partners, the Christian Democrats (Mrs Merkel’s party), also lost ground and finished with 17.6%, their lowest result in Berlin ever.

The two so-called “people’s parties” of post-war German politics, even when added together, thus have well short of half the seats in Berlin’s next assembly. Not only is their “grand coalition” no longer tenable; it is no longer even remotely grand.

This means that Berlin’s mayor, Michael Müller, a technocratic and uncharismatic Social Democrat, must find at least two other parties with which to form a majority. The AfD, as a pariah in the German party system, is excluded. Including the current partners, the Christian Democrats, is hard to imagine after the drubbing that voters just gave this coalition. That leaves The Left, a party that descends from East Germany’s communists; the Greens, a centre-left party considered closest to the Social Democrats; and the Free Democrats, a liberal party that has floundered in recent years but now seems nationally resurgent.

The likeliest coalition is a “red-red-green” alliance between the three parties of the left. Such a coalition already governs in Thuringia, but with The Left in the lead. What is acceptable in that eastern state, though—or in Berlin, the only state that contains both a formerly East and West German part—still horrifies many western Germans. The centre-right parties would certainly use the spectre of a “left republic” as a bogeyman during next year’s federal campaign. On current polls, red-red-green would have no majority.

That means, paradoxically, that all paths in the new six-party world lead to Mrs Merkel and the Christian Democrats staying in power. On September 19th Mrs Merkel conceded that the Berlin results, like those in other recent elections, are “very bitter” and that her refugee policy bears much of the blame. But she also knows that, come next autumn, even a battered and diminished Christian Democratic Union will be the only party in a position to bargain with coalition partners to form a majority, much as Berlin’s Social Democrats are doing now.

The question is thus not whether Mrs Merkel could win a fourth term (Germany has no term limits) in 2017. She can. It is whether she wants to run again. She herself, before becoming chancellor, once said that she wanted to find the right time to exit politics, lest she be carried out of office “a half-dead wreck”. And even without plausible alliances between the other parties against her in the Bundestag, opposition to her has been fierce inside her own conservative bloc.

The cheerleader of this opposition is Horst Seehofer, the premier of Bavaria and boss of the Christian Social Union, the Bavarian “sister party” to the Christian Democrats. By tradition the two parties campaign together for the same candidate for chancellor and form one group in the Bundestag. But for the past year, Mr Seehofer has attacked Mrs Merkel relentlessly over her refugee policy. He demands a fixed numerical limit for new refugees (even though the number of new arrivals is down anyway), an idea Mrs Merkel rejects. It is not yet clear whether the CSU will invite Mrs Merkel to its party gathering in November, as is customary. If the chancellor is brought down over her refugee policy, it will not be because of elections, but because of rebellion in her own bloc.

No comments:

Post a Comment