Supporters of greater independence for Hong Kong gain a foothold in the city’s legislature

ELECTIONS held on September 4th for Hong Kong’s legislature must have shocked the leadership in Beijing. In their highest turnout for any such poll in the territory’s history (58%), voters sent a clear signal of discontent with China’s attempts to stifle democracy. Even more worryingly for Chinese officials, some of them supported radicals who believe Hong Kong should decide its own future regardless of China’s wishes. Several such “localists” gained seats for the first time.

The results confirm that separatism has emerged as a powerful new force in Hong Kong. It has grown out of a failed campaign in 2014 to press the Chinese government to allow the territory’s leader to be directly elected by voters, with no attempt to filter out candidates deemed unacceptable to China’s ruling Communist Party. Leaders of that “Umbrella” movement are among six localists who were elected to the 70-member Legislative Council, known as Legco. Hong Kong’s government had tried to prevent this by requiring candidates to declare their support for Hong Kong’s status as part of China; several localists failed the test. That many have now gained seats will be viewed in Beijing as a big political challenge—the opening of a new front, as the party would see it, in a battle against separatism that already confounds it in Xinjiang, Tibet and independently governed Taiwan.

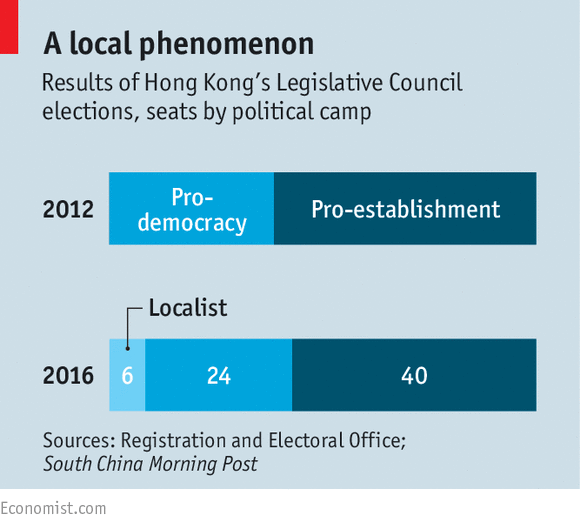

Voting arrangements for Legco ensured that pro-democracy politicians, including localists, had very little chance of taking a majority of the seats. Only 40 of them are elected through universal suffrage. The rest are chosen by members of “functional constituencies” representing various professions, businesses and social groups. These tend to be pro-establishment. But pro-government candidates did not do as well as they did in the previous elections for Legco in 2012. They kept their majority, but took only 40 seats, three fewer than last time. Of the 35 “geographical constituency” seats chosen by popular vote, 16 went to establishment candidates and 19 to a mixture of moderate democrats, localists, radicals of other stripes and independent candidates with pro-democracy leanings. With three other seats gained by universal suffrage, and eight in functional constituences, pro-democracy politicians retain their power to block some bills in Legco (see chart).

Hong Kong’s politicians had long been divided into two camps. One was usually described as “pro-government” or “pro-Beijing”. The other was called the “pan-democrats”, who wanted full democracy for Hong Kong but did not challenge China’s right to rule it. The elections have revealed a split in the pro-democracy camp between moderates prepared to work within the current system, and young, often highly educated, radicals.

Some of the localists gained their seats at the expense of veteran democrats. Days before the polls, however, five pro-democracy candidates withdrew in an effort to ensure victory for like-minded rivals, even radical ones. This may have helped Nathan Law of a party called Demosisto, who was a student leader during the Umbrella movement, become the youngest ever person to win a Legco seat. He describes himself as a “23-year-old kid”. Another localist, Eddie Chu Hoi-dick (pictured, with his hands in the air), picked up some 84,000 votes, the most cast for any candidate in a geographic constituency. Among veteran democrats who lost their seats were Frederick Fung, Cyd Ho and Lee Cheuk-yan.

Many in Hong Kong, however, still prefer candidates who do not challenge the status quo. Regina Ip won a seat in the constituency of Hong Kong Island, despite having served as the government’s security chief during its aborted attempt in 2003 to introduce a much-hated law against sedition. Among pro-establishment candidates fighting in geographic constituencies, Ms Ip gained the largest number of votes: around 60,000.

The high turnout, by Hong Kong’s standards, was probably helped by a growing political awareness among people in their late teens and early 20s, the generation that led the Umbrella protests. Many young people feel less bound by the political conventions of Hong Kong’s transition to Chinese rule in 1997, when even firebrand democrats described themselves as Chinese patriots. They believe China’s refusal to fulfil its promise to give the territory more democracy has left them little choice but to challenge China’s right to rule. Leaders in Beijing will fight them tooth and nail.

No comments:

Post a Comment