Federal data show that a viral video is representative of a broad pattern of aggressive overbooking

GETTING “bumped” from a flight took on a whole new meaning on April 9th, when United Airlines summoned aviation-security officers to drag a passenger off a plane kicking and screaming—literally. The company needed to transport employees from Chicago to Louisville, Kentucky, and the flight was too full to accommodate them. After no one accepted United’s offer of $1,000 to relinquish their seat, the airline selected an already-seated traveller at random and ordered him to disembark. When he refused—he is a doctor, and said he could not change planes because he had to attend to patients—he was physically removed from the flight against his will and, despite being bloodied, managed to sneak back on before being taken off again. The entire imbroglio was captured on video and has now been seen over 19m times around the world.

Involuntary denials of boarding (IDB), as they are formally dubbed, are rarely this contentious, but are a fact of life in commercial air travel. Because a small share of passengers generally fail to turn up—often simply because their previous flight arrived late—companies usually offer a few more tickets for sale than they can actually accommodate, counting on no-shows to maximise the chances that a plane departs exactly at its full capacity. Although their finely tuned statistical models usually manage to avoid mishaps, every so often the systems underestimate the number of travellers who will turn up, forcing carriers to “bump” excess passengers to a subsequent flight. Most of the time they can find volunteers to accept financial compensation in exchange for a later arrival. When no one is willing to wait, conflict can ensue.

Overbooking is fairly common: over half a million passengers in the United States were left at the gate in 2016 holding valid tickets for a flight. However, the vast majority of this group did so freely, enticed by whatever goodies the airlines offered for their seats: 8.6% of all denials of boarding that year were involuntary. From 2008-15, only 50,000 travellers on American flights per year were booted against their will, a rate of one for every 10,400 passengers.

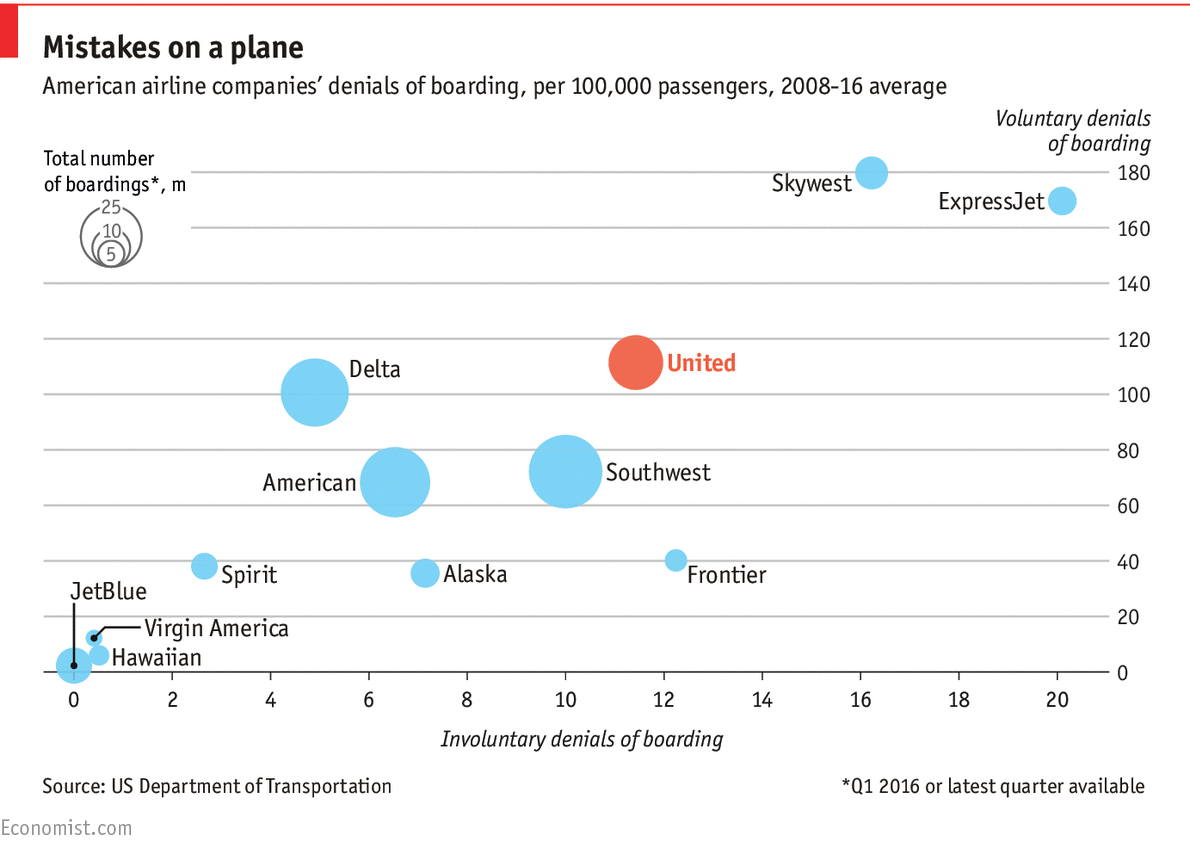

That said, different carriers employ different overbooking strategies, making the risk of getting bumped—or, for flexible voyagers, the opportunity of extracting juicy compensation for a brief delay—highly dependent on your choice of airline. The worst offenders are ExpressJet and SkyWest, both subsidiaries of SkyWest, Inc. Since 2008, these eager overbookers have involuntarily denied boarding to 20 and 16, respectively, of every 100,000 passengers who showed up to fly. Unsurprisingly, they also led the pack in asking for volunteers for a bump, striking such a deal with 170 and 180 flyers out of every 100,000. At the other extreme, the safest bets are JetBlue, Hawaiian Airlines and Virgin America (which was recently acquired by Alaska Airlines). JetBlue, which eschews the industry’s prevailing hub-and-spoke route system in favour of direct point-to-point travel, tends to have far fewer passengers making connections, and is the rare carrier that does not overbook at all.

And what about United, whose name will now be synonymous in the public eye with violent overbooking for the foreseeable future? With an IDB rate of 11.6 passengers out of every 100,000, it is certainly no ExpressJet. However, that still makes it by far the most bump-prone of the United States’s large airlines: American’s rate is over 40% lower, and Delta’s 55%. Travellers on United can only hope that the company might ease off its relatively aggressive overbooking policy in response to this public-relations nightmare.

Involuntary denials of boarding (IDB), as they are formally dubbed, are rarely this contentious, but are a fact of life in commercial air travel. Because a small share of passengers generally fail to turn up—often simply because their previous flight arrived late—companies usually offer a few more tickets for sale than they can actually accommodate, counting on no-shows to maximise the chances that a plane departs exactly at its full capacity. Although their finely tuned statistical models usually manage to avoid mishaps, every so often the systems underestimate the number of travellers who will turn up, forcing carriers to “bump” excess passengers to a subsequent flight. Most of the time they can find volunteers to accept financial compensation in exchange for a later arrival. When no one is willing to wait, conflict can ensue.

Latest updates

That said, different carriers employ different overbooking strategies, making the risk of getting bumped—or, for flexible voyagers, the opportunity of extracting juicy compensation for a brief delay—highly dependent on your choice of airline. The worst offenders are ExpressJet and SkyWest, both subsidiaries of SkyWest, Inc. Since 2008, these eager overbookers have involuntarily denied boarding to 20 and 16, respectively, of every 100,000 passengers who showed up to fly. Unsurprisingly, they also led the pack in asking for volunteers for a bump, striking such a deal with 170 and 180 flyers out of every 100,000. At the other extreme, the safest bets are JetBlue, Hawaiian Airlines and Virgin America (which was recently acquired by Alaska Airlines). JetBlue, which eschews the industry’s prevailing hub-and-spoke route system in favour of direct point-to-point travel, tends to have far fewer passengers making connections, and is the rare carrier that does not overbook at all.

And what about United, whose name will now be synonymous in the public eye with violent overbooking for the foreseeable future? With an IDB rate of 11.6 passengers out of every 100,000, it is certainly no ExpressJet. However, that still makes it by far the most bump-prone of the United States’s large airlines: American’s rate is over 40% lower, and Delta’s 55%. Travellers on United can only hope that the company might ease off its relatively aggressive overbooking policy in response to this public-relations nightmare.

No comments:

Post a Comment