Bosses are under increasing pressure to take stances on social issues. How should they respond?

Rules of thumb for navigating the era of activism

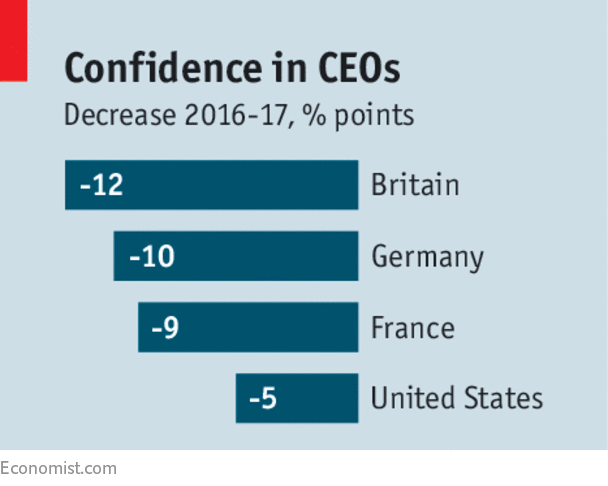

Some of these spats between the Oval Office and the corner office reflect Mr Trump’s peculiar style of governing. But they point to something bigger, too (see article). Executives who would rather concentrate on commerce are finding it ever harder to avoid politics, in America and beyond.

Latest updates

Consumers can now express their opinions dramatically online. Keurig Green Mountain, a maker of coffee machines, recently tweeted that it had halted advertising on a Fox News programme whose host had appeared to defend Roy Moore, a Senate candidate accused of dating and assaulting teenagers. Afterwards consumers posted videos of themselves bashing Keurig machines. As one commenter pointed out, everyone might feel less cranky if they stopped boycotting coffee firms. But that wouldn’t save bosses from controversy.

Employees, many of them in the big, Democrat-leaning metropolitan areas where large companies are often based, increasingly demand that their firms take positions on issues ranging from gay rights to climate change. Nearly half of young American employees say they would be more loyal if their boss took a public position on a social issue. A big test came in 2015, when Indiana was considering a “religious freedom” bill that would have let firms and non-profit organisations discriminate against gay and transgender people; Apple and Salesforce.com were among those to oppose it, saying it would harm their customers and staff.

And shareholders are judging firms on broader criteria than financial ones. Investments that considered environmental, social and governance factors accounted for $13.3trn of assets under management in 2012; that sum was $22.9trn in 2016. Over a fifth of the funds under professional management in America fall into this category, up from a ninth in 2012.

Not every company faces the same pressures: a consumer-facing firm needs to be more attuned than a corporate-facing one. Nor is there a simple recipe for how a business should best balance purely commercial goals with the competing interpretations of its social responsibilities from employees, customers and shareholders. But to help them navigate the era of activism, CEOs should bear two rules of thumb in mind.

The profitable is political

The first is to be consistent. Firms can no longer spout platitudes about corporate “values”; independent watchdogs and staff stand ready to brand discrepancies as hypocrisy. Google recently became a model of what to avoid. An employee wrote a memo on women and tech firms; Google fired him, saying the memo violated its code of conduct and created a hostile environment for women. That undermined free speech (which Google vows to defend online) and called attention to how the firm fails the group it was claiming to protect (it is under scrutiny for paying men more than women).The second is to adopt an old Goldman Sachs mantra, of being “long-term greedy”. CEOs have to watch quarterly results. But to maximise the long-run value of their firms, they must anticipate the shifting preferences of various constituencies, from staff and customers to regulators and investors. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s boss, warned last month that heavier investments in online policing would squeeze short-term earnings, but said that this would protect the firm’s long-term health. He might have done well to reach that conclusion sooner. Anticipating changes to political and social norms is hard. But it is a vital part of the CEO’s job description.

No comments:

Post a Comment