by Jenny Feder and Biodun Iginla, Political News Analysts, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Jerusalem

The police recommend that he be indicted for corruption, but he hangs on

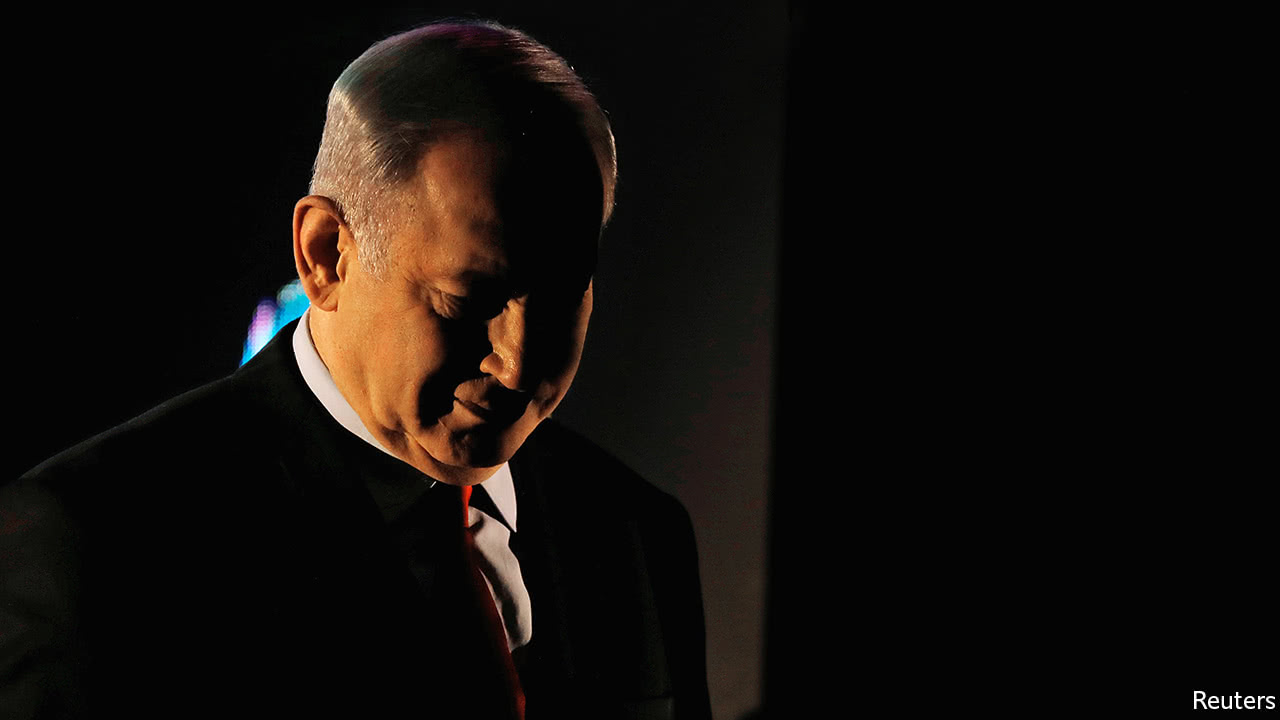

NORMALLY composed, Binyamin Netanyahu looked rattled. Addressing the nation on February 13th, he began by recounting his 50 years of service, from the days in which he led commandos in battle as a young special-forces officer, through his service as Israel’s swashbuckling ambassador to the UN and his term as a reform-minded finance minister. It was expansive self-flattery, even for him. Yet he needed to show how indispensable his leadership is to Israel’s security and prosperity, for the prime minister was embarking on a battle for political survival.

An hour earlier the police had told his lawyers that they were recommending he face charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust in relation to two investigations that have lasted more than 16 months. He felt shocked and betrayed. Israel’s police chief, Roni Alsheikh, is a former agent-handler and spymaster in Shin Bet, the internal security service. Mr Netanyahu had picked him to run the police, hoping that the favour would be repaid in loyalty. Instead Mr Alsheikh subjected him to the most forensic of probes.

The police recommendations, which have now been handed over to Israel’s attorney-general, include six separate charges of bribery and conspiracy to bribe, against Mr Netanyahu and two of Israel’s best-connected business figures. The police say they conspired to change legislation on tax breaks for expatriates, build a tax-free zone on the border with Jordan, alter the ownership of Israel’s main commercial television channels and arrange discreet distribution agreements between competing newspapers.

In the process, Mr Netanyahu and his wife received crates of champagne, boxes of Cuban cigars and the occasional gift of jewellery. The police estimate the gifts were worth a total of 1m shekels ($280,000). Mr Netanyahu says he has not done anything wrong.

For the moment Mr Netanyahu’s coalition is stable. None of its members has spoken out against the prime minister since the police recommendations were published. In private some of the key ministers have said that they think the accusations are credible. However, they are afraid they will lose the support of their voters if they provoke the downfall of their right-wing government. They are waiting for the attorney-general’s decision on whether to indict before coming out against him.

That passes the ball to Avichai Mendelblit, a cautious and ponderous advocate who served as Mr Netanyahu’s cabinet secretary for three years. Although Mr Mendelblit’s integrity is not in doubt, he is reluctant as a civil servant to start proceedings that could bring down the government. Far better, from his point of view, would be for Mr Netanyahu to resign before an indictment is issued, as happened in the case of Ehud Olmert, a former prime minister, who was jailed for corruption.

Over the past decade Israel’s justice system has jailed not just a former prime minister, but also a former president, Moshe Katzav, who was convicted of rape. Some might see the incarceration of two high-ranking leaders as proof that Israeli politicians are dishonest. Yet it is also something for Israel to be proud of, for it shows that its justice system and free press hold even the most powerful to account.

Faced with Mr Netanyahu, a dominant figure in Israeli politics who first came to power in 1996 and has served a total of 12 years as prime minister, these safeguards are being tested as never before. Start with the justice system. Mr Netanyahu has long insisted that he had only received “gifts from friends” and that all his actions were “for the good of the nation”. Now he has gone further, calling the police report “a biased, extreme document [that is] as full of holes as a Swiss cheese and doesn’t hold water”. Moreover, he has questioned the integrity of his investigators, saying they could not be trusted and accusing them of trying to thwart the electorate’s will and bring down a serving prime minister.

His attacks on the press are also intensifying. He has tried to pass legislation aimed at muzzling it and, as has now been revealed by the police charges, has allegedly been involved in secret dealings with media-owners to get favourable coverage. It is to the credit of Israeli journalists, police investigators and prosecutors that they have not been deterred. But if such attacks continue, they will surely take a toll.

Ultimately the question is how long Mr Netanyahu believes he can carry on. In public and private, he has given no sign that he will step down. There is no precedent for an Israeli prime minister continuing to serve under an indictment. In 1977 Yitzhak Rabin resigned rather than be charged for holding money in an overseas bank account that was not declared to the tax authorities.

Early in his first term as prime minister, Mr Netanyahu himself only narrowly escaped being indicted on another corruption charge. He has indicated that even if the attorney-general indicts him this time, he intends to remain in office and prove his innocence in court. Legal opinions are divided as to whether such a step would be constitutional and it is certain to be tested in the Supreme Court.

The leaders of his coalition partners, as well as senior figures in his Likud party, would be wise not to let matters reach the point where judges are called on to decide on the legitimacy of an elected prime minister. Mr Netanyahu believes he is indispensable and can brazenly stay in power, even if that means breaking traditions. Israel will pay the price, in damage to its justice system and institutions.

An hour earlier the police had told his lawyers that they were recommending he face charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust in relation to two investigations that have lasted more than 16 months. He felt shocked and betrayed. Israel’s police chief, Roni Alsheikh, is a former agent-handler and spymaster in Shin Bet, the internal security service. Mr Netanyahu had picked him to run the police, hoping that the favour would be repaid in loyalty. Instead Mr Alsheikh subjected him to the most forensic of probes.

Latest stories

In the process, Mr Netanyahu and his wife received crates of champagne, boxes of Cuban cigars and the occasional gift of jewellery. The police estimate the gifts were worth a total of 1m shekels ($280,000). Mr Netanyahu says he has not done anything wrong.

For the moment Mr Netanyahu’s coalition is stable. None of its members has spoken out against the prime minister since the police recommendations were published. In private some of the key ministers have said that they think the accusations are credible. However, they are afraid they will lose the support of their voters if they provoke the downfall of their right-wing government. They are waiting for the attorney-general’s decision on whether to indict before coming out against him.

That passes the ball to Avichai Mendelblit, a cautious and ponderous advocate who served as Mr Netanyahu’s cabinet secretary for three years. Although Mr Mendelblit’s integrity is not in doubt, he is reluctant as a civil servant to start proceedings that could bring down the government. Far better, from his point of view, would be for Mr Netanyahu to resign before an indictment is issued, as happened in the case of Ehud Olmert, a former prime minister, who was jailed for corruption.

Over the past decade Israel’s justice system has jailed not just a former prime minister, but also a former president, Moshe Katzav, who was convicted of rape. Some might see the incarceration of two high-ranking leaders as proof that Israeli politicians are dishonest. Yet it is also something for Israel to be proud of, for it shows that its justice system and free press hold even the most powerful to account.

Faced with Mr Netanyahu, a dominant figure in Israeli politics who first came to power in 1996 and has served a total of 12 years as prime minister, these safeguards are being tested as never before. Start with the justice system. Mr Netanyahu has long insisted that he had only received “gifts from friends” and that all his actions were “for the good of the nation”. Now he has gone further, calling the police report “a biased, extreme document [that is] as full of holes as a Swiss cheese and doesn’t hold water”. Moreover, he has questioned the integrity of his investigators, saying they could not be trusted and accusing them of trying to thwart the electorate’s will and bring down a serving prime minister.

His attacks on the press are also intensifying. He has tried to pass legislation aimed at muzzling it and, as has now been revealed by the police charges, has allegedly been involved in secret dealings with media-owners to get favourable coverage. It is to the credit of Israeli journalists, police investigators and prosecutors that they have not been deterred. But if such attacks continue, they will surely take a toll.

Ultimately the question is how long Mr Netanyahu believes he can carry on. In public and private, he has given no sign that he will step down. There is no precedent for an Israeli prime minister continuing to serve under an indictment. In 1977 Yitzhak Rabin resigned rather than be charged for holding money in an overseas bank account that was not declared to the tax authorities.

Early in his first term as prime minister, Mr Netanyahu himself only narrowly escaped being indicted on another corruption charge. He has indicated that even if the attorney-general indicts him this time, he intends to remain in office and prove his innocence in court. Legal opinions are divided as to whether such a step would be constitutional and it is certain to be tested in the Supreme Court.

The leaders of his coalition partners, as well as senior figures in his Likud party, would be wise not to let matters reach the point where judges are called on to decide on the legitimacy of an elected prime minister. Mr Netanyahu believes he is indispensable and can brazenly stay in power, even if that means breaking traditions. Israel will pay the price, in damage to its justice system and institutions.

No comments:

Post a Comment