by Maria Ogryzlo and Biodun Iginla, Political News Analysts, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Moscow

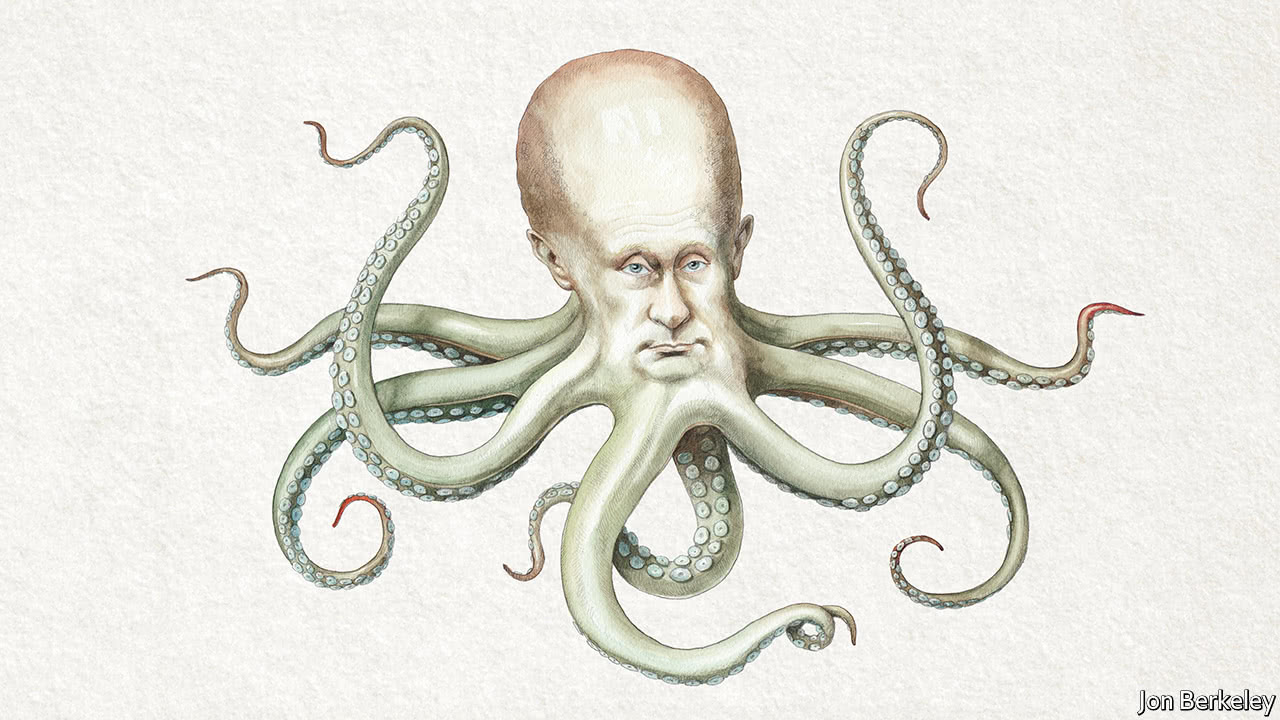

How Putin meddles in Western democracies

And why the West’s response is inadequate

IN THE late 1980s, as Mikhail Gorbachev launched perestroika, Russia made peace with the West. It was possible to believe that each would give up trying to subvert the other with lies and cold-war conspiracy theories. With the indictment of 13 Russians on February 16th by the American special counsel, Robert Mueller, it is clear just how fragile that belief was.

Mr Mueller alleges that in 2014 Russia launched a conspiracy against America’s democracy, and he believes he has the evidence to withstand Russian denials and a court’s scrutiny. Perhaps because Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, thought the CIA was fomenting an uprising in Ukraine, the Internet Research Agency, backed by an oligarch with links to the Kremlin, set up a trolling team, payments systems and false identities. Its aim was to widen divisions in America and, latterly, to tilt the vote in 2016 from Hillary Clinton to Donald Trump.

Europe has been targeted, too. Although the details are sketchier, and this is not the focus of the Mueller probe, Russia is thought to have financed extremist politicians, hacked computer systems, organised marches and spread lies (see Briefing). Again, its aim seems to have been to deepen divides.

It is futile to speculate how much Russia’s efforts succeeded in altering the outcomes of votes and poisoning politics. The answer is unknowable. But the conspiracies are wrong in themselves and their extent raises worries about the vulnerabilities of Western democracies. If the West is going to protect itself against Russia and other attackers, it needs to treat Mr Mueller’s indictments as a rallying cry.

With a modest budget, of a little over $1m a month, and working mostly from the safety of St Petersburg, the Russians managed botnets and false profiles, earning millions of retweets and likes. Other, better-funded, groups exploit similar techniques. Nobody yet knows how the outrage they generate changes politics, but it is a fair guess that it deepens partisanship and limits the scope for compromise.

Hence the second lesson, that the Russia campaign did not create divisions in America so much as hold up a warped mirror to them. It played up race, urging black voters to see Mrs Clinton as an enemy and stay at home on polling day. It sought to inflame white resentment, even as it called on progressives to vote for Jill Stein, of the Green Party. After Mr Trump’s victory, which it had worked to bring about, it organised an anti-Trump rally in Manhattan. Right after the Parkland school shooting, Russian bots began to pile into the debate about gun control (see article). Europeans are to a lesser degree divided, too, especially in Brexit Britain. The divisions that run so deep within Western democracies leave them open to intruders.

The most important lesson is that the Western response has been woefully weak. In the cold war, America fought Russian misinformation with diplomats and spies. By contrast, Mr Mueller acted because two presidents fell short. Barack Obama agonised over evidence of Russian interference but held back before eventually imposing sanctions, perhaps because he assumed Mr Trump would lose and that for him to speak out would only feed suspicions that, as a Democrat, he was manipulating the contest. That was a grave misjudgment.

Mr Trump’s failing is of a different order. Despite having access to intelligence from the day he was elected, he has treated the Russian scandal purely in terms of his own legitimacy. He should have spoken out against Mr Putin and protected America against Russian hostility. Instead, abetted by a number of congressional Republicans, he has devoted himself to discrediting the agencies investigating the conspiracy and hinted at firing Mr Mueller or his minders in the Justice Department, just as he fired James Comey as head of the FBI. Mr Mueller is not done. Among other things, he still has to say whether the conspiracy extended to the Trump campaign. Were Mr Trump to sack him now, it would amount to a confession.

Then comes resilience, which starts at the top. Angela Merkel successfully warned Mr Putin that there would be consequences if he interfered in German elections. In France Emmanuel Macron frustrated Russian hackers by planting fake e-mails among real ones, which discredited later leaks when they were shown to contain false information. Finland teaches media literacy and the national press works together to purge fake news and correct misinformation.

Resilience comes more easily to Germany, France and Finland, where trust is higher than in America. That is why retaliation and deterrence also matter—not, as in the cold war, through dirty tricks, but by linking American co-operation over, say, diplomatic missions, to Russia’s conduct and, if need be, by sanctions. Republican leaders in Congress are failing their country: at the least they should hold emergency hearings to protect America from subversion in the mid-term elections. Just now, with Mr Trump obsessively blaming the FBI and Democrats, it looks as if America does not believe democracy is worth fighting for.

Mr Mueller alleges that in 2014 Russia launched a conspiracy against America’s democracy, and he believes he has the evidence to withstand Russian denials and a court’s scrutiny. Perhaps because Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, thought the CIA was fomenting an uprising in Ukraine, the Internet Research Agency, backed by an oligarch with links to the Kremlin, set up a trolling team, payments systems and false identities. Its aim was to widen divisions in America and, latterly, to tilt the vote in 2016 from Hillary Clinton to Donald Trump.

Latest stories

It is futile to speculate how much Russia’s efforts succeeded in altering the outcomes of votes and poisoning politics. The answer is unknowable. But the conspiracies are wrong in themselves and their extent raises worries about the vulnerabilities of Western democracies. If the West is going to protect itself against Russia and other attackers, it needs to treat Mr Mueller’s indictments as a rallying cry.

Trolleology

They hold three uncomfortable lessons. One is that social media are a more potent tool than the 1960s techniques of planting stories and bribing journalists. It does not cost much to use Facebook to spot sympathisers, ferret out potential converts and perfect the catchiest taglines (see article). With ingenuity, you can fool the system into favouring your tweets and posts. If you hack the computers of Democratic bigwigs, as the Russians did, you have a network of bots ready to dish the dirt.With a modest budget, of a little over $1m a month, and working mostly from the safety of St Petersburg, the Russians managed botnets and false profiles, earning millions of retweets and likes. Other, better-funded, groups exploit similar techniques. Nobody yet knows how the outrage they generate changes politics, but it is a fair guess that it deepens partisanship and limits the scope for compromise.

Hence the second lesson, that the Russia campaign did not create divisions in America so much as hold up a warped mirror to them. It played up race, urging black voters to see Mrs Clinton as an enemy and stay at home on polling day. It sought to inflame white resentment, even as it called on progressives to vote for Jill Stein, of the Green Party. After Mr Trump’s victory, which it had worked to bring about, it organised an anti-Trump rally in Manhattan. Right after the Parkland school shooting, Russian bots began to pile into the debate about gun control (see article). Europeans are to a lesser degree divided, too, especially in Brexit Britain. The divisions that run so deep within Western democracies leave them open to intruders.

The most important lesson is that the Western response has been woefully weak. In the cold war, America fought Russian misinformation with diplomats and spies. By contrast, Mr Mueller acted because two presidents fell short. Barack Obama agonised over evidence of Russian interference but held back before eventually imposing sanctions, perhaps because he assumed Mr Trump would lose and that for him to speak out would only feed suspicions that, as a Democrat, he was manipulating the contest. That was a grave misjudgment.

Mr Trump’s failing is of a different order. Despite having access to intelligence from the day he was elected, he has treated the Russian scandal purely in terms of his own legitimacy. He should have spoken out against Mr Putin and protected America against Russian hostility. Instead, abetted by a number of congressional Republicans, he has devoted himself to discrediting the agencies investigating the conspiracy and hinted at firing Mr Mueller or his minders in the Justice Department, just as he fired James Comey as head of the FBI. Mr Mueller is not done. Among other things, he still has to say whether the conspiracy extended to the Trump campaign. Were Mr Trump to sack him now, it would amount to a confession.

How to win the woke citizens vote

For democracy to thrive, Western leaders need to find a way to regain the confidence of voters. This starts with transparency. Europe needs more formal investigations with the authority of Mr Mueller’s. Although they risk revealing intelligence sources and methods and may even please Russia—because proof of its success sows mistrust—they also lay the ground for action. Party-funding laws need to identify who has given money to whom. And social media should be open to scrutiny, so that anyone can identify who is paying for ads and so that researchers can more easily root out subterfuge.Then comes resilience, which starts at the top. Angela Merkel successfully warned Mr Putin that there would be consequences if he interfered in German elections. In France Emmanuel Macron frustrated Russian hackers by planting fake e-mails among real ones, which discredited later leaks when they were shown to contain false information. Finland teaches media literacy and the national press works together to purge fake news and correct misinformation.

Resilience comes more easily to Germany, France and Finland, where trust is higher than in America. That is why retaliation and deterrence also matter—not, as in the cold war, through dirty tricks, but by linking American co-operation over, say, diplomatic missions, to Russia’s conduct and, if need be, by sanctions. Republican leaders in Congress are failing their country: at the least they should hold emergency hearings to protect America from subversion in the mid-term elections. Just now, with Mr Trump obsessively blaming the FBI and Democrats, it looks as if America does not believe democracy is worth fighting for.

No comments:

Post a Comment