by Biodun Iginla and Tokun Lawal, Political News Analysts, The Economist and BBC News, Abuja/London

Three cheers for democracy

Muhammadu Buhari was the least bad presidential candidate in Nigeria. May he rise to his task

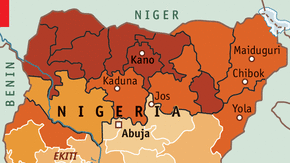

One big reason to cheer is that Mr Jonathan has been such a dismal failure. So has his People’s Democratic Party (PDP), which has run Nigeria ever since the generals gave way to an elected civilian government in 1999. His administration has woefully failed to defeat an insurgency by Boko Haram, an Islamist extremist group that has tormented Nigeria’s north-east over the past few years. Mr Jonathan tried to improve farming and provide electricity to all, but proved unable to rebuild much of Nigeria’s hideously decrepit infrastructure. Above all, he was unwilling to tackle corruption, the country’s greatest scourge and the cause of much of its chaos. When the central bank’s respected governor complained that $20 billion had been stolen, Mr Jonathan sacked him. Nigeria is the biggest producer of oil on the continent, but most of its 170m-plus people still live on less than $2 a day. That is an indictment of successive governments.

Thanks to the resilience and vitality of ordinary Nigerians, the economy has been growing fast, especially around Lagos, the thriving commercial hub. But that is largely despite the government, not because of it. And with the oil price sharply down, Nigerians could well become even poorer.

Nobody can be sure that the 72-year-old Mr Buhari will turn things around fast, if at all. His brief stint as the country’s leader 32 years ago, when he was a general, was little better than Mr Jonathan’s. His human-rights record was appalling. He detained thousands of opponents, silenced the press, banned political meetings and had people executed for crimes that were not capital offences when they were committed. He expelled 700,000 immigrants under the illusion that this would create jobs for Nigerians. His economic policies, which included the fixing of prices and bans on “unnecessary” imports, were both crass and ineffective.

Yet there is reason to hope that he has learnt from past mistakes. Although not always with a good grace, Mr Buhari accepted defeat in three previous presidential elections. As a northerner, a Muslim and a former soldier, he has a better chance of restoring the morale of Nigeria’s miserable army, which is essential if it is to defeat Boko Haram. His All Progressives Congress is a ramshackle coalition of parties, but the calibre of a number of its leading lights is superior to that of the greedy and incompetent bigwigs who dominate the PDP. Above all, Mr Buhari, whose style is strikingly ascetic, has a reputation for honesty. Corruption in Nigeria is so ingrained that nobody should expect him to root it out overnight. But it is vital that the new president makes a start. His vice-presidential running mate is a pastor who has fought hard for human rights and cleaner government.

Setting an example

Since 1991, when an incumbent leader on the African continent—in

little Benin—was for the first time peacefully ejected at the ballot box

after three decades without genuine democracy, at least 30 governments

and presidents have been voted out of office. Though that is an

incomparably better record than in the Arab world, Africa has recently

become patchier again. Mr Jonathan’s magnanimous concession of victory

to Mr Buhari will be a terrific boost to democrats across the continent.

Just hope and pray that Mr Buhari does not let them down.

No comments:

Post a Comment