Africa

by Tokun Lawal, Rashida Adjani, and Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Lagos/London

How Africa’s most important failure can at last come right

Yet within a few years its hopes were dashed. Nigeria suffered the first of many military coups in 1966 and was torn apart by civil war the next year. Corruption spread rapidly, hollowing out institutions and preventing the government from providing even basic services. After decades of theft and misrule, the most populous nation in Africa—and its biggest economy—has come perilously close to fragmentation. In January this year much of the north-east was overrun by bloodthirsty jihadists. Many expected that the elections which took place at the end of March would be so rigged as to give another term to Goodluck Jonathan, a singularly ineffectual president, and that opposition-supporting areas in the north would rise up in protest. The previous elections, judged among Nigeria’s fairest yet, had led to more than 700 deaths.

Instead Nigeria confounded not just its critics but itself. The elections were peaceful and, despite some ballot-box stuffing, roughly reflected the will of the majority. The election of the opposition candidate, Muhammadu Buhari, marks the first democratic defeat of a Nigerian president running for re-election as well as the best opportunity to tackle the country’s many problems. As our special report in this issue lays out, Nigeria, at last, has a chance to change.

Goodluck to Buhari

Sceptics will scoff that every new dawn in Nigeria for the past

half-century has proved false. Yet there are three reasons for optimism.

The first, believe it or not, is Mr Buhari himself. Although he was a

military dictator in the 1980s and presided over human-rights abuses,

his rebirth as a democrat seems genuine. He also appears to be honest,

and determined to do something about those who are not. He has warned

officials—and his own relatives—to expect no mercy if they are caught

stealing. Cronies of the previous regime take him seriously: even before

his inauguration in May, they were said to be negotiating the return of

stolen money in exchange for amnesty.The election itself gives another reason for hope. Having experienced their first cleanish vote, Nigerians may prove less tolerant of rigging in the future. It is a salutary lesson that a sitting president, with all the resources of the state at his disposal, can lose. It suggests that voters will punish misrule. Other entrenched and corruption-riddled ruling parties, such as South Africa’s, are watching nervously.

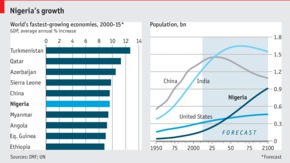

Last, Nigeria’s middle class is growing rapidly. For all its flaws, Nigeria is less atrociously governed than it was in the mid-1990s, when its ruler, Sani Abacha, was both tyrannical and economically illiterate. Growth has averaged more than 7% a year for the past decade, creating opportunities for bright young Nigerians to make a good living honestly. Instead of jostling to join the government in order to extract rents from their fellow citizens, many are flocking to start businesses. Smartphones and social media have helped fuel this growth, and are also making Nigeria more transparent. Motorists shaken down for bribes by cops can now film the interaction and post it to YouTube. During the elections volunteers photographed the tally at individual voting stations and posted the results on Twitter, reducing the scope for mischief. Nigeria’s diaspora helps, too. More than 1m Nigerians live in the rich world, mainly in America and Britain. Having tasted cleaner government abroad, many now expect better back home.

Mr Buhari’s greatest tasks will be to fight corruption and improve security. These are in fact linked, since a rotten, thieving state breeds unrest and is inept at quelling it. Early this year Nigeria had lost almost all of three northern provinces to Boko Haram, a rabble of Islamists who are fond of pillage and murder but object to education, especially of girls. The group succeeded for a while because no one stopped it. Nigerian officers allegedly sold weapons to the enemy, leaving their own troops ill-equipped for the fight. Boko Haram was pushed back only when the army of a neighbouring country, Chad, intervened. Mr Buhari needs to clean up and discipline the army. Ordering the generals who are supposed to fight the jihadists out of their air-conditioned offices in the capital and into headquarters closer to the action was a good start.

Things come together?

To clamp down on corruption more broadly, Mr Buhari must both reduce

the opportunities for it and also catch and punish the perpetrators. An

obvious early step would be to audit the country’s oil revenues

properly. By one estimate, a third of these are stolen before they even

reach the treasury.Another way to reduce the scope for graft would be to reduce the role of the state in the economy. Nigeria has too many onerous regulations, and officials demand bribes not to enforce them. It also has policies that invite abuse—such as price controls on petrol, which must be sold at below-market rates, with fat subsidies to compensate the sellers. Too often, the subsidies are stolen and the fuel finds its way onto the black market, leaving chronic shortages at petrol stations. Abolishing subsidies and deregulating prices would stem the theft of billions of dollars. Mr Buhari should also cut Nigeria’s sky-high tariffs on imports (which promote smuggling), liberalise power and gas prices (which are so low that they discourage investment in the energy sector), and allow private firms to build and operate the roads, bridges and railways that Nigerian farmers and firms so desperately need to get their produce to market.

Nigeria matters because it is the biggest country in the continent that has huge potential for catch-up growth. If it fails, it could bring down half a dozen neighbouring states with it. If Mr Buhari turns it round, it could be both the engine room of Africa and an inspiration for people everywhere who are tired of predatory government and long to clip its claws.

No comments:

Post a Comment