Weapons technology

by Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit, New York/London

The military playing field is more even than it has been for many years. That is a big problem for the West

“We are entering an era where American dominance on the seas, in the skies, and in space—not to mention cyberspace—can no longer be taken for granted,” admitted Chuck Hagel, the outgoing secretary of defence, last year. He argued that America urgently needed to develop a new generation of military technologies, lest another country come to feel capable of challenging it. His warning was timely.

The others are certainly growing more assertive. China is increasingly keen to press its territorial claims in the western Pacific. Russia is intent on re-establishing its influence in what it regards as its “near abroad”, as it has shown in Ukraine. Less powerful but more reckless states such as North Korea and Iran might also become more inclined to make mischief if they believe they can inflict so much damage on the American forces that seek to punish them that Washington will think twice about doing so.

Repeating history

The effort that Mr Hagel called for is known as the “third offset

strategy”, because it is the third time since the second world war that

America has sought technological breakthroughs to offset the advantages

of potential foes and reassure its friends. The first such moment

occurred in the early 1950s, when the Soviet Union was fielding far

larger conventional forces in Europe than America and its allies could

hope to repel. The answer was to extend America’s lead in nuclear

weapons to counter the Soviet numerical advantage—a strategy known as

the “New Look”.A second offset strategy was conceived in the mid-1970s. American military planners, reeling from the psychological defeat of the Vietnam war, recognised that the Soviet Union had managed to build an equally terrifying nuclear arsenal. They had to find another way to restore credible deterrence in Europe. Daringly, America responded by investing in a family of untried technologies aimed at destroying enemy forces well behind the front line. Precision-guided missiles, the networked battlefield, reconnaissance satellites, the Global Positioning System (GPS) and radar-beating “stealth” aircraft were among the fruits of that research.

Bob Work, the deputy secretary of defence charged with overseeing the new offset strategy, says that by the mid-1980s Soviet generals who studied the results of early demonstrations of the operational concept that became known as Air-Land Battle realised what they were up against. “We were an aggressive first mover,” Mr Work says. “We had picked an area that we knew our most likely adversary couldn’t copy.” The impact of this “revolution in military affairs” was hammered home in 1991 during the first Gulf war. Iraqi military bunkers were reduced to rubble and Soviet-style armoured formations became sitting ducks. Watchful Chinese strategists, who were as shocked as their Soviet counterparts had been, were determined to learn from it.

The large lead that America enjoyed then has dwindled. Although the Pentagon has greatly refined and improved the technologies that were used in the first Gulf war, these technologies have also proliferated and become far cheaper. Colossal computational power, rapid data processing, sophisticated sensors and bandwidth—some of the components of the second offset—are all now widely available.

And America has been distracted. During 13 years of counter-insurgency and stabilisation missions in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Pentagon was more focused on churning out mine-resistant armoured cars and surveillance drones than on the kind of game-changing innovation needed to keep well ahead of military competitors. America’s combat aircraft are 28 years old, on average. Only now is the fleet being recapitalised with the expensive and only semi-stealthy F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

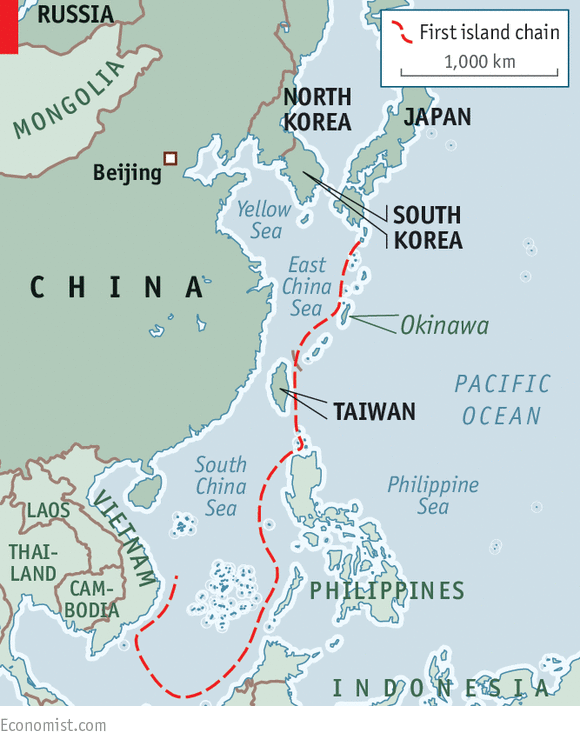

The Chinese call their objective “winning a local war in high-tech conditions”. In effect, China aims to make it too dangerous for American aircraft-carriers to operate within the so-called first island chain (thus pushing them out beyond the combat range of their tactical aircraft) and to threaten American bases in Okinawa and South Korea. American strategists call it “anti-access/area denial”, or A2/AD.

Damage, not defeat

The concern for America’s allies in the region is that, as China’s

military clout grows, the risks entailed in defending them from bullying

or a sudden aggressive act—a grab of disputed islands to claim mineral

rights, say, or a threat to Taiwan’s sovereignty—will become greater

than an American president could bear. Some countries might then decide

to throw in their lot with the regional hegemon.Although China is moving exceptionally quickly, Russia too is modernising its forces after more than a decade of neglect. Increasingly, it can deploy similar systems. Iran and North Korea are building A2/AD capabilities too, albeit on a smaller scale than China. Even non-state actors such as Hizbullah in Lebanon and Islamic State in Syria and Iraq are acquiring some of the capabilities that until recently were the preserve of military powers.

Hence the need to come up with a third offset strategy. But the economic, political and technical circumstances are very different from the ones that prevailed in the 1950s or the 1970s. America needs to develop new military technologies that will impose large costs on its adversaries, even as budget caps ordered by Congress are squeezing its own defence spending.

The programme needs to overcome at least five critical vulnerabilities. The first is that carriers and other surface vessels can now be tracked and hit by missiles at ranges from the enemy’s shore which could prevent the use of their cruise missiles or their tactical aircraft without in-flight refuelling by lumbering tankers that can be picked off by hostile fighters. The second is that defending close-in regional air bases from a surprise attack in the opening stages of a conflict is increasingly hard. Third, aircraft operating at the limits of their combat range would struggle to identify and target mobile missile launchers. Fourth, modern air defences can shoot down non-stealthy aircraft at long distances. Finally, the satellites America requires for surveillance and intelligence are no longer safe from attack.

It is an alarming list. Yet America has considerable advantages, argues Robert Martinage of the Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, an influential Washington think-tank that has consistently drawn attention to the need to counter Chinese A2/AD capabilities. Those advantages include unmanned systems, stealthy aircraft, undersea warfare and the complex systems engineering that is required to make everything work together.

Over the next decade or so, America will aim to field unmanned combat aircraft that are stealthy enough to penetrate the best air defences and have the range and endurance to pursue mobile targets. Because they have no human pilots, fewer are needed for training. Since they do not need to rest, they can fly more missions back to back. And small, cheaper American drones might be used to swarm enemy air defences.

Drones are widespread these days, but America has nearly two decades of experience operating them. And the new ones will be nothing like the vulnerable Predators and Reapers that have been used to kill terrorists in Yemen and Waziristan. Evolving from prototypes like the navy’s “flying wing” X-47B and the air force’s RQ-180, they will be designed to survive in the most hostile environments. The more autonomous they are, the less they will have to rely on the control systems that enemies will try to disrupt—though autonomy also raises knotty ethical and legal issues.

Out of sight

Some of the same technologies could be introduced to unmanned

underwater vehicles. These could be used to clear mines, hunt enemy

submarines in shallow waters, for spying and for resupplying manned

submarines, for example, with additional missiles. They can stay dormant

for long periods before being activated for reconnaissance or strike

missions. Big technical challenges will have to be overcome: Mr

Martinage points out that the vehicles will require high-density energy

packs and deep undersea communications.Contracts will be awarded this summer for a long-range strike bomber, the first new bomber since the exotic and expensive B-2 began service two decades ago. The B-3, of which about 100 are likely to be ordered, will also have a stealthy, flying-wing design. This time, costs will be kept down by using proven technologies, but with a modular approach to allow for upgrades to be simply plugged in when necessary to counter improving air defences. Targets for the B-3, perhaps supported by unmanned aircraft, will include mobile missile launchers and command bunkers.

If surface vessels, particularly aircraft-carriers, are to remain relevant, they will need to be able to defend themselves against sustained attack from precision-guided missiles. The navy’s Aegis anti-ballistic missile-defence system is capable but expensive: each one costs $20m or so. If several of them were fired to destroy an incoming Chinese DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missile, the cost for the defenders might be ten times as much as for the attackers.

If carriers are to stay in the game, the navy will have to reverse that ratio. Hopes are being placed in two technologies: electromagnetic rail guns, which fire projectiles using electricity instead of chemical propellants at 4,500mph to the edge of space, and so-called directed-energy weapons, most likely powerful lasers. The rail guns are being developed to counter ballistic missile warheads; the lasers could protect against hypersonic cruise missiles. In trials, shots from the lasers cost only a few cents. The navy has told defence contractors that it wants to have operational rail guns within ten years.

Defending against salvoes of incoming missiles will remain tricky and depend on other technological improvements, such as compact long-range radars that can track multiple targets. Finding ways to protect communications networks, including space-based ones, against attack is another priority. Satellites can be blinded by lasers or disabled by exploding missiles. One option would be to use more robust technologies to transmit data—such as chains of high-altitude, long-endurance drones operating in relays.

The technical challenges and potential costs involved in all this are large. And they will have to be tackled in fresh ways. Rather than staying within the closed loop of military R&D departments and the defence industry, much of the research the Pentagon needs is being done by consumer technology companies in Silicon Valley and elsewhere. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, algorithms, big-data processing, 3D printing, compact high-density power systems and tiny sensors of the kind found in smartphones will all be crucial. That raises the risk of a culture clash: though both are hot for innovation, the Pentagon operates rather differently from the consumer tech industry, to put it mildly.

The second offset strategy succeeded partly because of political will. Congress and the White House walked in step, with continuity from one administration to the next. The new offset strategy, too, appears to have widespread support. Congress is keen. Mr Hagel’s successor as defence secretary, Ash Carter, has spent three decades at the leading edge of science and weapons technology.

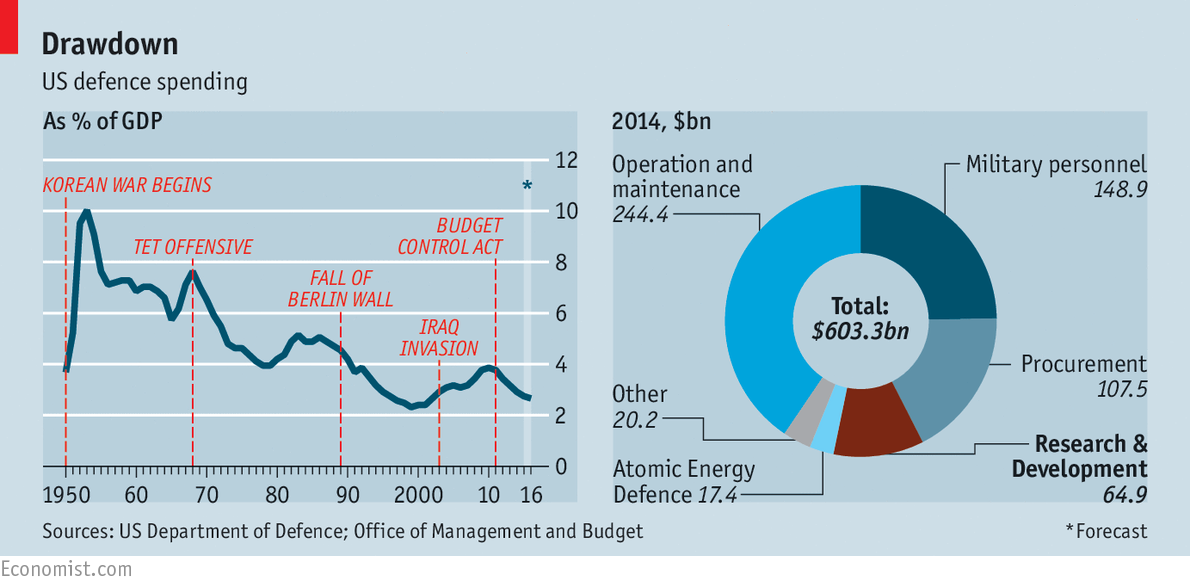

But Washington is far more confrontational than it was a few decades ago. Bipartisan agreement is hard to find and even harder to sustain. Stand-offs over the budget have made it exceedingly difficult for the Pentagon to plan ahead. Research and development spending, which accounts for about 10% of the defence budget (see chart) will have to be not just protected but increased.

To get its hands on the technologies it needs, the military establishment and the armed forces themselves may have to take an axe to cherished programmes. One possibility would be to scale back plans to buy nearly 2,500 F-35 fighter jets, which have too short a range for many situations, and use the money to buy unmanned combat aircraft and a bigger fleet of long-range strike bombers. The navy might have to give up on two of its fabulously expensive carrier groups in recognition of their growing vulnerability in favour of investments in submarines, both manned and unmanned. None of this will be easy. The men who command air forces tend to be former fast-jet pilots still in love with their steeds; the sailors who run navies are attached to the muscular power that only big surface ships can display. The army, too, will have to shrink.

Third time unlucky?

Even if all these obstacles are overcome, it is unlikely that a third

offset strategy will secure Western military dominance for as long as

the first two did. Technology spreads much more quickly these days,

partly thanks to the internet, which the Pentagon helped to create and

which now helps rival powers steal America’s military secrets.

Technological change of all kinds has become speedier, too, thanks to

fierce competition in fashion-conscious consumer markets.The second offset strategy benefited from some unusual circumstances that left America as the world’s unchallenged hyperpower after the end of the cold war. That world has vanished. In the military-technological struggle to come, the contest will be relentless and the victories probably more fleeting.

Finally, a warning. Despite the success of the second offset strategy, it never fully dealt with the possibility that a losing power might resort to nuclear weapons. The logic of nuclear deterrence, it was assumed (or hoped), would survive an intense conventional conflict. The cheerleaders for a new offset strategy rarely mention nuclear weapons.

Yet if a foe comes to believe it might win what the great strategist Thomas Schelling called “a competition in risk-taking”—an idea that Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, actively encourages—the rational response to the other side’s technological superiority might be nuclear brinkmanship. As Elbridge Colby of the Centre for a New American Security argues: “The more successful the offset strategy is in extending US conventional advantages, the more attractive US adversaries will find strategies of nuclear escalation.” The enemy always gets a vote.

No comments:

Post a Comment