by Nasra Ismail and Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Cairo

Islamic State may be lashing out abroad because it has been weakened nearer home; but it will still be hard to take down

“ENDURING and expanding”: Islamic State’s alliterative motto leaves out its burning desire to eradicate everything else, but otherwise sums up its ambitions pretty well. If IS has, in recent times, seemed more concerned with the enduring bit, its history shows that it has never long lost sight of expanding in any way possible: by capturing territory, by spawning offshoots far and wide, by inspiring new recruits, and by spreading fear. As a state with puny resources and no real friends, it needs to be a moving target.

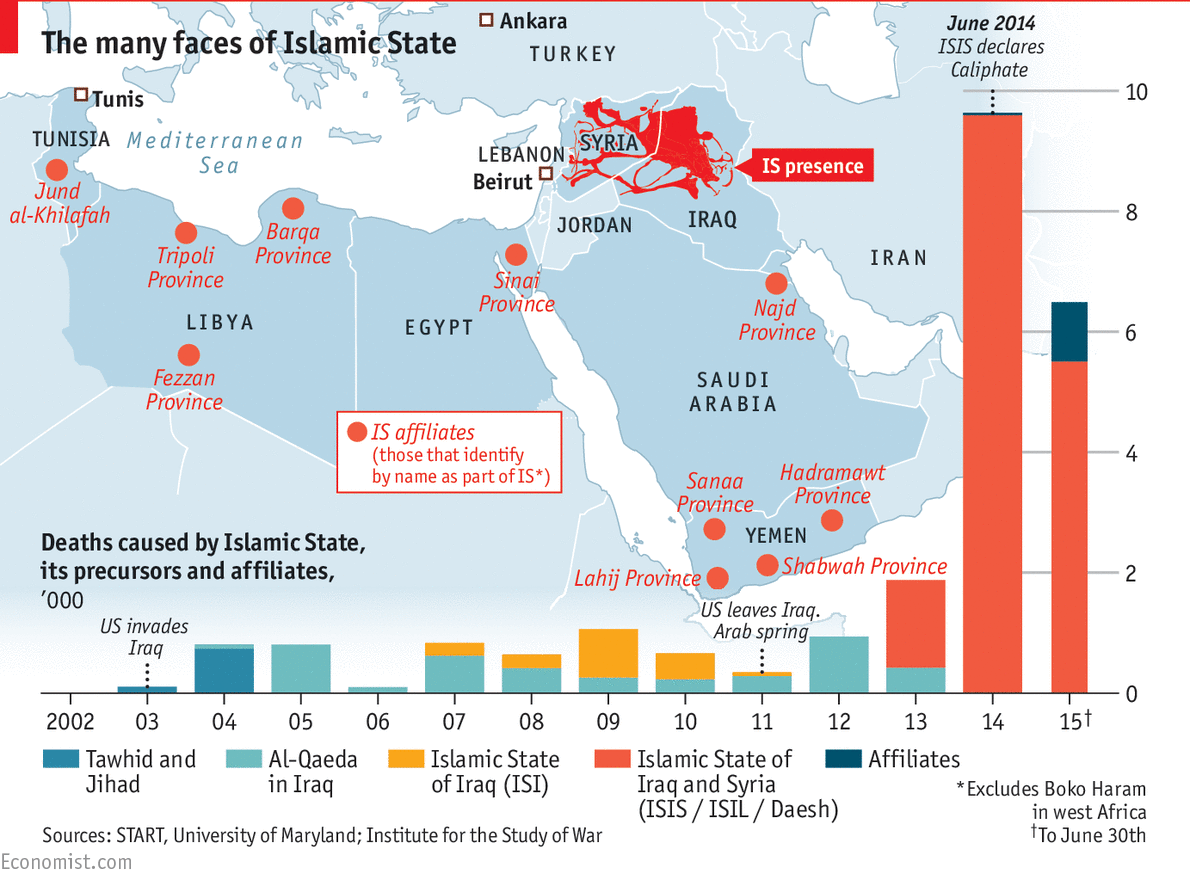

It is not clear to what extent recent strikes by IS beyond the boundaries of the territory it has carved out of Syria and Iraq mark a change of course. Its various affiliates—some 36 groups around the world have declared allegiance to IS’s secretive caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi—have been mounting terrorist attacks for some time (see chart). A recent survey by the New York Times estimated that these offshoots have killed perhaps 1,000 civilians since January via mosque bombings in Yemen, attacks on tourists in Tunisia and suicide-bombs in Ankara and Beirut (the figure excludes the murderous rampages of Boko Haram in Nigeria). The group has also encouraged “lone-wolf” acts by like-minded would-be terrorists. But the death toll over the past few weeks seems to take things to a new level.

It may be a coincidence that plots to murder hundreds in Paris, blow up an aircraft over Sinai and kill indiscriminately on the streets in Beirut all came to fruition so close together. They may have been long planned; similar attempts earlier may have been thwarted. But it may also be a considered response to challenges that IS faces closer to home.

Pentagon sources say that coalition air strikes killed 20,000 IS fighters in the 14 months after their onset in August 2014. That sounds over-optimistic. But it is certain that a number of commanders have been among the dead. The intense fighting at Kobane, a Kurdish enclave in northern Syria to which IS laid siege last September, eventually being driven back by heavy air strikes in December, is thought to have cost it 2,000 men. An IS defector told Michael Weiss, an American journalist, that the losses were at least twice that, and that tightening of the Turkish border had made it harder for IS to replace fallen fighters. He said it was partly in response to this that IS turned to attacks on the “far enemy”. Single, dramatic attacks are an immense force-multiplier in propaganda terms.

Losses on the scale of Kobane are doubtless a blow but not, alas, a fatal one. Estimates of the group’s military manpower range from about 30,000 (America’s Central Intelligence Agency) to about 100,000 (Hisham al-Hashimi, an Iraqi security expert). Mr Hashimi reckons about 20% are foreign-born, a similar figure to that given in UN papers.

Factor into these figures the fact that IS fighters seem a lot more effective than those who oppose them. When the Iraqi city of Tikrit was recaptured last April, it took 30,000 soldiers from the Iraqi army and associated Shia militias to overcome 1,000 IS fighters. When IS took the Iraqi city of Ramadi, its forces were outnumbered ten to one by the defenders.

A willingness to use kamikaze tactics is definitely part of what gives IS forces an edge; but they are also innovative, well-drilled and better led than many of those they face. In April IS used a drone to record its troops taking an oil refinery and distributed the footage on the internet. A former American Green Beret, quoted by McClatchy, a news service, said the attackers showed “quiet tactical confidence: correct movement, intervals, fire discipline”.

Fighting well is not enough

Despite these impressive fighters, IS has recently been losing ground, largely because its adversaries have air power. Kurdish forces captured Sinjar in Iraq, along with adjacent territory in Syria, and IS forces are being pushed back elsewhere in Iraq, too. With help from Russian aircraft and Iranian-backed militias, Syrian government forces recently relieved an airbase near Aleppo to which IS had long laid siege. Following the deaths of 224 Russians in the Metrojet airliner bombing of October 31st, Russia may now be targeting IS in preference to other enemies of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

Yet IS endures. Indeed its territory remains one of the safer parts of Syria: aid officials in Turkey say that in September and October as many as 70,000 civilians fled to Islamic State from the province of Homs. Coalition bombing in the caliphate is much less indiscriminate than that of the Russian and Syrian air forces elsewhere. What is more, food is cheaper and there is justice of a sort. There is also a functioning economy, largely thanks to an estimated 20,000-30,000 barrels of oil pumped daily from captured fields in eastern Syria and northern Iraq.

Its dependence on oil revenues—they provide around $50m a month, according to investigative reporting by the Financial Times—is just one way in which IS looks more like an old-fashioned Arab dictatorship than a new Islamic Utopia. It doles out alms to the poor in exchange for total obedience. It promotes a cult of personality around Mr Baghdadi. It churns out turgid propaganda about repaired bridges and newly opened schools. Like all the region’s successful autocracies, it has created multiple and mutually suspicious security services, the better to stave off coups.

In the wake of the Paris attacks, military action aimed at denying IS its territorial base seem likely. The firepower available to IS’s enemies dwarfs all that it can muster. In an interview with the BBC, the security chief of Iraq’s Kurdish region reckoned that, given the necessary will, the job could be done in months or even weeks. France has already ramped up its aerial attacks and Russia, now fielding heavy bombers, says it will double the number of daily sorties. American aircraft are attacking new targets in the group’s oil infrastructure. Recent strikes, preceded by warnings for civilians to escape, have destroyed hundreds of tanker trucks. America has also boosted supplies to Kurdish and other Syrian rebel forces on the IS frontlines.

The area IS controls seems likely to shrink under such pressure. But the capture of large cities like Raqqa and Mosul will require a far bigger effort on the ground. And as Sinjar and Kobane have shown, the cost will be high: both those towns now lie in ruins. The challenge is not just the diplomatic and military one of mustering, motivating, co-ordinating and deploying sufficient forces, huge though that is. It is also humanitarian: such action is likely to displace still more desperate refugees, and leave them little to return to.

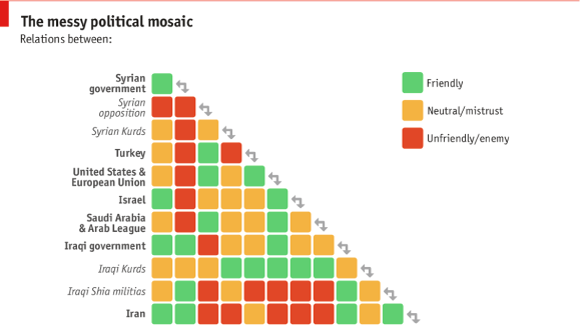

The Western powers and Russia are not keen to send troops. They are even less keen to be left holding ravaged and probably hostile territory. Iraq’s forces are overstretched and deeply distrusted by many of the Sunnis they would liberate; many prefer the rule of IS to that of Shia militias. Syria’s forces are exhausted, overstretched and loyal to a regime responsible for war crimes. Local powers such as Iran, Turkey, the Kurds and Saudi Arabia have a range of conflicting agendas; eliminating IS is at the top of none of them.

There is progress to be made that does not need boots on the streets of Raqqa. Better police work can help; it is already producing results in Turkey, which has rounded up several cells in recent weeks. Improved planning and communication between anti-IS forces in the field would help, too. Trust, lamentably absent today, must be built.

Breaking up the would-be caliphate militarily would destroy the aura of invincibility which constitutes a large part of its attraction. But successor groups, and even more, IS’s ideology, will endure for as long as the poisonous swamp it inhabits persists. A partial list of its ingredients includes a hyped-up sense of Sunni victimhood, indoctrination by xenophobic Wahhabists, the dismal anomie and yearning for heroism of some young urban Muslims in Europe and elsewhere, and the rage generated by brutal and repressive regimes such as Syria’s. It has pooled and festered across the band of collapsed and failing states that stretches from Algeria to Pakistan. It will take more than a hot sun, or heavy firepower, to make it evaporate.

No comments:

Post a Comment