by Xian Wan and Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Beijing

Click bait

Homoerotic fiction is doing surprisingly well—among straight women

E-foxy

E-foxy

Ms Sheng became instantly hooked on the homoerotic tale with its subtle portrayal of a form of sexual desire that is rarely discussed openly in China (homosexuality was considered a mental illness until 2001). She found the novel more appealing than the saccharine love stories popular among other heterosexual Chinese women like her.

Danmei, meaning “indulgence in beauty”, is China’s version of what is often called “slash” fiction in other countries. The genre takes its English name from the slash sometimes used in synopses of such works to separate the names of often well-known protagonists: Kirk/Spock, or in this case fox king/nobleman (the men, despite their attraction to each other, are portrayed as straight). The genre sometimes explores taboos: incest, intergenerational sex, or sex with a character who is disfigured. It is also inspired by Japanese manga comic books with their whimsical illustrations (the word danmei was originally a Japanese term: tanbi). The genre is only available online in China—no state-owned publisher would dare print such works, for fear of violating laws against pornography.

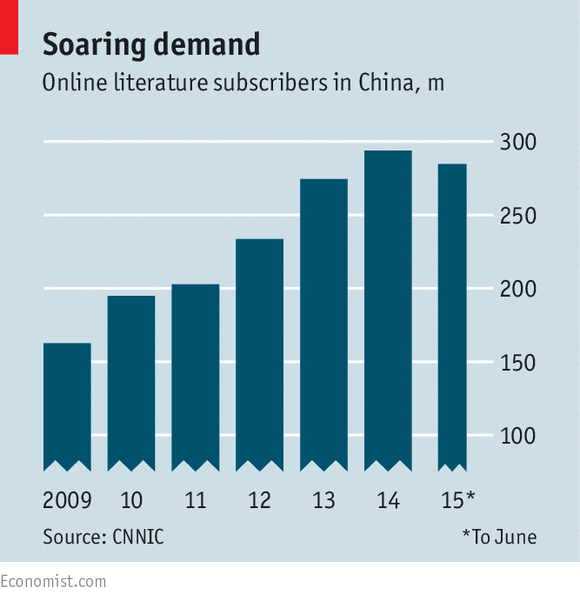

Among younger Chinese women and teenagers, danmei is proving remarkably popular: websites devoted to it have large followings. Katrien Jacobs, an expert on Chinese online pornography at the University of Hong Kong, estimates that in every high school or university class, there is at least one fan of danmei. If so, that could mean a readership in the hundreds of thousands. Ms Jacobs says danmei attracts readers by creating “a sense of rebellion” against a culture in which women are often expected to be obedient and conventional. Readers delight in enjoying the forbidden.

In 2011 the authorities shut down a danmei website and, the following year, jailed its (male) founder for 18 months. In less than three years it had published 1,200 works of fiction, many of them reportedly written by young women. Most of the time, however, censors appear preoccupied with stopping the spread of hard-core pornography and material critical of the Communist Party. Danmei usually avoids graphic descriptions of sex, and steers clear of politics.

Crackdowns certainly do not bother Ms Sheng. She identifies herself as a funu, or “rotten girl”—a pun on the word for woman that readers of danmei sometimes use ironically to describe themselves. She says she will continue buying and sharing the works of her favourite authors from Taiwan and Hong Kong (where such fiction is legal), despite the risks in China.

No comments:

Post a Comment