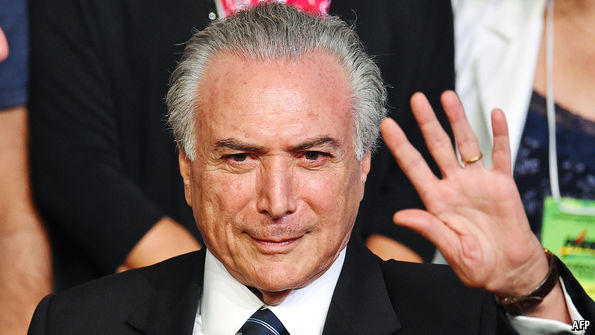

An unplanned presidency

Michel Temer has better ideas than Dilma Rousseff. That does not mean he will be a successful president

As The Economist went to press, Brazil was bracing itself for its third unplanned presidency in as many decades. In the early hours of May 12th the Senate voted to open the impeachment trial of President Dilma Rousseff. Under the law, she must now step aside for up to 180 days while the chamber considers her fate. Michel Temer, the vice-president, will now move into the Planalto, as the presidential palace is known. If the Senate votes by a two-thirds majority to convict Ms Rousseff, Mr Temer would serve out the rest of her term, which ends in 2018.

Despite the high stakes and chaos surrounding the impeachment process, it now seems inconceivable that some last-minute reversal could keep Ms Rousseff in office. That nearly happened on May 9th, when the Speaker of Congress’s lower house annulled a vote by that chamber to forward the impeachment motion to the Senate. Hours later he changed his mind. But it now looks virtually certain that Mr Temer will become president, at least for a while. How he acquits himself could affect Brazil’s fortunes for years to come.

His job will be harder than the one faced by earlier unelected presidents. After five years of inept rule by Ms Rousseff, Brazil is suffering its worst recession since the 1930s. The economy will probably shrink by a total of 7.5% in 2015 and 2016; the unemployment and inflation rates both stand at around 10%. The budget deficit is more than a tenth of GDP. Nearly as acute as the economic crisis is the political one caused by the scandal surrounding Petrobras, the state-controlled oil company. This has tarnished both Ms Rousseff’s Workers’ Party (PT) and the centrist Party of the Brazilian Democratic Movement (PMDB) of Mr Temer.

The multi-talented Mr Temer

His claim to the presidency, unlike that of his forerunners, is

bitterly contested. Ms Rousseff and her allies denounce the impeachment

process as a “coup”. On the eve of the Senate vote pro-PT protesters put

up barricades and blocked roads in several Brazilian states. The more

Mr Temer tries to reverse Ms Rousseff’s disastrous policies, the more

her supporters will accuse him of overturning the verdict of the voters

who re-elected her in 2014.Mr Temer has offsetting strengths. Temperamentally, he is nearly the opposite of the unpopular Ms Rousseff. While she is gruff, he is charming. Mr Temer is eloquent. Ms Rousseff inspired the coinage of the word dilmês, meaning garbled oratory. She is stubborn. Mr Temer, the youngest of eight children, is conciliatory. Ms Rousseff had never held elected office until she became president. Mr Temer was elected to Congress four times and was Speaker of the lower house. He has written dry tomes (a bestselling textbook on constitutional law) and moist verse (collected in “Anonymous Intimacy”).

Although Mr Temer rarely challenged his boss’s economic interventionism, he believes in a blend of economic and social liberalism that is unusual in Brazil. As one of the drafters of the constitution adopted in 1988, he opposed its employment-stifling protections for workers. He was against the death penalty (which was banned for civil crimes) and in favour of legal abortions (which are still outlawed in most cases).

As the PMDB’s 13-year alliance with the PT began falling apart, Mr Temer’s closet liberalism came out into the open. Last October his party published “Bridge to the Future”, an 18-page manifesto that laments the enterprise-sapping effects of Brazil’s overlarge state, which claims 36% of GDP in taxes while providing poor public services. Though short on detail, the document advocates a series of sensible measures, from privatisations and freer trade to reform of over-generous public pensions, sclerotic labour laws and the Byzantine tax code.

Judging by the ministers Mr Temer is expected to appoint, he intends to carry out some of these proposals. Henrique Meirelles, an inflation-busting governor of the Central Bank under Ms Rousseff’s predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, will probably be the new finance minister. Seasoned PMDB operators will probably serve as chief of staff (Eliseu Padilha), planning minister (Romero Jucá) and as super-minister for infrastructure, a new job (Moreira Franco). Mr Temer is expected to compensate for the loss of the PT’s votes in Congress by bringing into government the centre-right Party of Brazilian Social Democracy (PSDB).

Swift reforms, especially cuts to public spending, would, despite the recession, boost confidence, curb inflation and allow the Central Bank to start reducing its target interest rate from a growth-crushing 14.25%. Mr Temer may chop the number of ministries from 32 to 23 to please voters who think the government should make sacrifices, too. That would be an astonishing decision for a man from the PMDB, where the unifying characteristic is the quest for patronage. Such prospects have stirred euphoria in the financial markets, which would otherwise be depressed by the miserable state of the economy.

Things could easily go wrong. The first problem is the PMDB’s role in the Petrobras scandal, which fuels the fury that is driving Ms Rousseff from office, though it does not provide the legal grounds for her impeachment. Six of the PMDB’s sitting congressmen, including Mr Jucá, are under investigation. On May 5th the supreme court suspended Eduardo Cunha, the PMDB Speaker of the lower house, from Congress after indicting him for corruption. Mr Cunha and the others deny wrongdoing.

The electoral authority is investigating whether Petrobras-related bribes helped finance the re-election campaign of Ms Rousseff and Mr Temer. If it unearths irregularities, it could annul the results, evicting Mr Temer from office. A new election would allow Brazilians to choose leaders untainted by scandal, which would be welcome. But the uncertainty leading up to them would unsettle the economy. Mr Temer argues that the PMDB’s coffers were separate from the PT’s, and above board.

A second worry is that the new president, despite his backroom flair, may fail to secure majorities for reforms. At the best of times, congressmen are reluctant to vote for spending cuts and tax rises. Their attention will soon shift to the Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro, which take place in August, and then to October’s local elections. The latter will be more important than usual. The Petrobras scandal has cut the flow of illicit money to political parties; last year the supreme court barred corporate donations. So candidates for national office in 2018 will rely on local officials elected this year to usher their voters to the polls. Austerity will not appeal to congressmen already thinking about their re-election campaigns two years hence.

Mr Temer could forgo immediate budget cuts in favour of fundamental reforms, such as delinking pensions from the minimum wage and granting independence to the Central Bank. But these measures would run up against a third problem: the perception, especially among Ms Rousseff’s supporters, that Mr Temer has no mandate to do anything important. In 2014 voters rejected a blander version of Mr Temer’s reforms, put forward by the PSDB’s losing candidate, Aécio Neves. Impeachment is bringing about not just a change of personnel but a change of political philosophy that Brazilians did not vote for. It may be legal, but it is not legitimate, said Celso Amorim, a former foreign and defence minister, in an interview with the BBC.

Most Brazilians, delighted to see Ms Rousseff gone, are not pleased about Mr Temer coming in. He and a majority of the most important members of his prospective team are septuagenarians with centuries of political baggage between them. Just 8% of Brazilians think they will do a better job than Ms Rousseff and her colleagues. Mr Temer might be able to change their minds, if he can enact the controversial reforms he espouses and Brazilians feel the economic benefits. The question is whether the newly promoted vice-president will get that chance.

No comments:

Post a Comment