Daily chart

by Biodun Iginla, The Economist Intelligence Unit, London

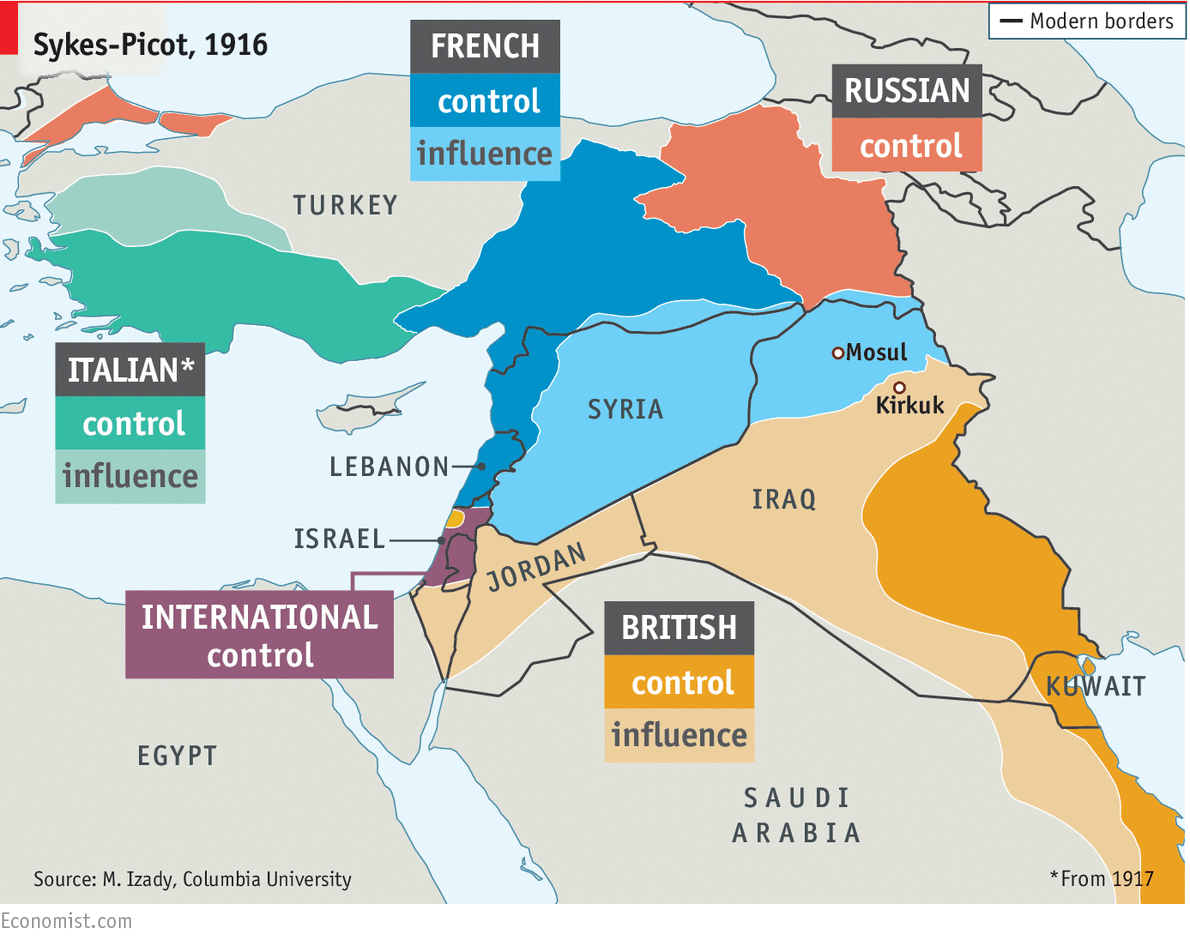

THE MODERN frontiers of the Arab world only vaguely resemble the blue and red grease-pencil lines secretly drawn on a map of the Levant on May 16th 1916, at the height of the first world war. Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot were appointed by the British and French governments respectively to decide how to apportion the lands of the Ottoman empire, which had entered the war on the side of Germany and the central powers. The Russian foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, was also involved. The Allies agreed that Russia would get Istanbul, the sea passages from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, and Armenia; the British would get Basra, Hafia and southern Mesopotamia; and the French a slice in the middle, including Lebanon, Syria and Cilicia (in modern-day Turkey). Palestine would be an international territory. In between the French- and British-ruled blocs, large swathes of territory, mostly desert, would be allocated to the two powers’ respective spheres of influence. Italian claims were added in 1917. But after the defeat of the Ottomans in 1918 these lines changed markedly with the fortunes of war and diplomacy. Sykes-Picot has become a byword for imperial treachery. George Antonius, an Arab historian, called it a shocking document, the product of “greed allied to suspicion and so leading to stupidity”. It was, in fact, one of three separate and irreconcilable wartime commitments that Britain made to France, the Arabs and the Jews. The resulting contradictions have been causing grief ever since.

Read more about Sykes-Picot and its aftermath here and the full special report on the Arab world here.

No comments:

Post a Comment